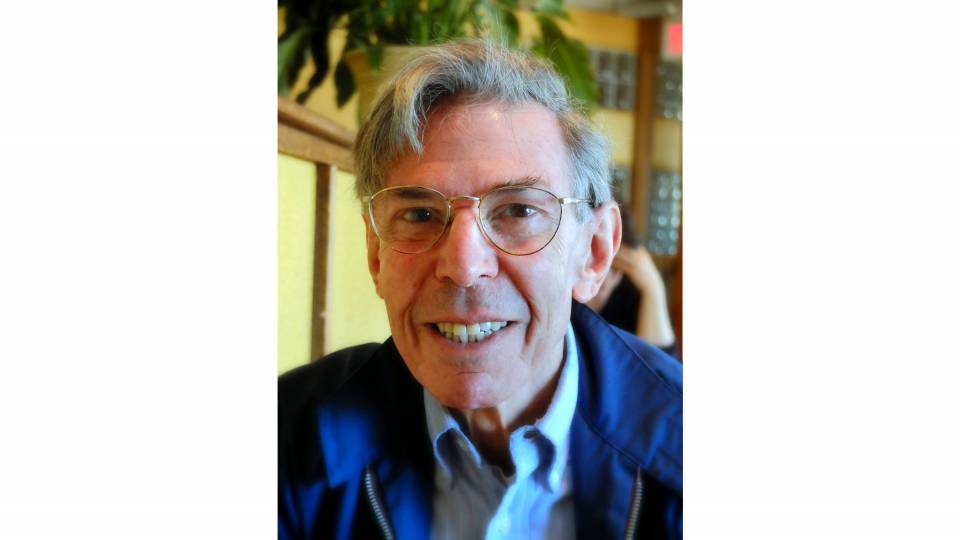

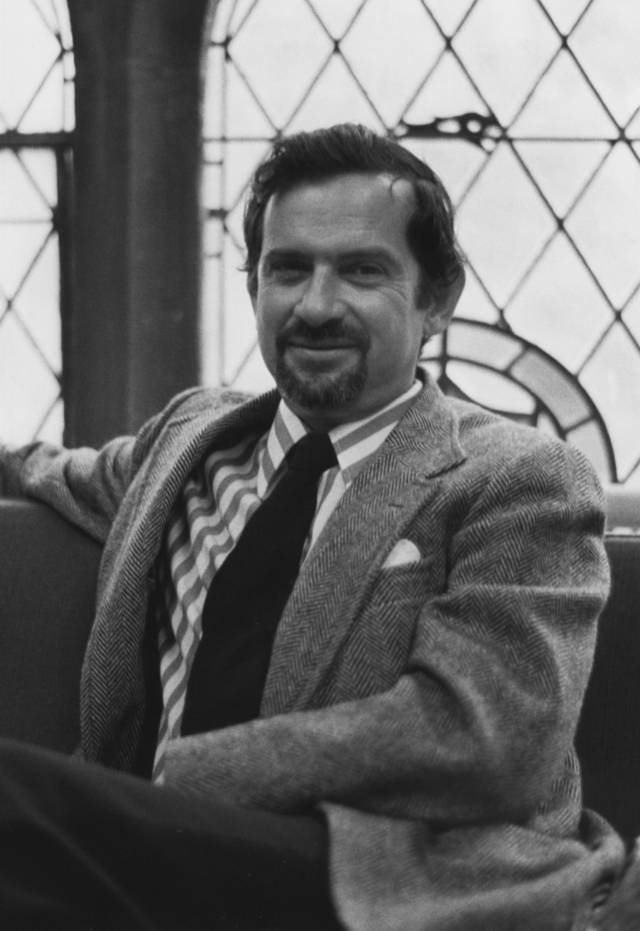

Léon-François Hoffmann, a Princeton professor of French and Italian, emeritus, died peacefully at his home in Princeton, New Jersey, on May 25. He was 86.

Léon-François Hoffmann

Hoffmann became an assistant professor at Princeton in 1960, a year after earning his Ph.D. in Romance languages and literatures from the University. Previously, he taught at Princeton as a graduate student and an instructor. He transferred to emeritus status in 2003. Hoffmann earned his bachelor's degree from Yale University.

Hoffmann was a specialist in 19th-century French literature and Caribbean literature in French, notably the literature of Haiti. Along with teaching on these subjects, he developed seminars on French language, literature and culture in former French colonial territories.

"François Hoffmann was a central figure in French studies at Princeton for many years," said Thomas Trezise, professor of French and Italian and department chair. "He promoted awareness of the francophone world outside of France and, above all, drew our attention to Haitian history and culture." Trezise said faculty and students appreciated Hoffman's "ironic and often self-deprecating sense of humor.'"

Hoffmann was born in Paris on April 11, 1932. As a graduate student at Princeton, he came across an anthology of Haitian poetry in the library and was fascinated by what he called its "somewhat different semantics" and "original use of the French language."

He traveled to Haiti in 1956 and began to publish articles about Haitian poetry. He would return to Haiti many times throughout his career. He also learned Creole, which was necessary to understand the literature; though most Haitian literature is written in French, it contains Creole words and turns of phrase.

In his office in East Pyne was a map of Haiti, on which he plotted his travels throughout the country with red pushpins.

"He knew more than almost anyone else in the country about Haiti and its somewhat neglected literature and culture — and about the culture of the Caribbean in general, having spent some of his formative years there after his family fled France [to Cuba] to escape the Nazis in WWII," said Lionel Gossman, the M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Romance Languages and Literatures, Emeritus.

Gossman said Hoffmann's home and office were full of "fascinating and often quite beautiful artifacts collected on his travels and, above all, in Haiti." Hoffman's travels included India, where he taught for a time, and Afghanistan, during the relatively less dangerous period between the Russian withdrawal and the American involvement in that country's affairs, Gossman said.

"As a result, he brought a unique perspective to the department, long before interest in francophone and the non-Western world became normal among teachers and students of French literature and culture," Gossman said.

His books include "Le Nègre romantique," about the image of blacks in the French collective imagination that won a prize from the Académie Française, and "Le Roman haïtien," which won the Gilbert Chinard Prize. He also wrote two books on the image of Spain in French Romantic literature, “Romantique Espagne” and “La Peste à Barcelone.”

Hoffmann also wrote several textbooks, including "L'Essentiel de la grammaire française" and "Le français en français." He wrote many articles for academic publications and served as American correspondent for two French journals. He also produced critical editions of a novel by Alexandre Dumas père, "Georges," and of Alphonse de Lamartine's play "Toussaint Louverture."

"Hoffmann's expertise in, and love for, the Romantic era never diminished," said François Rigolot, the Meredith Howland Pyne Professor of French Literature, Emeritus, and professor of French and Italian, emeritus. In 2002, Hoffman co-organized an international symposium at Princeton for the bicentennial of Victor Hugo's birth, and edited the proceedings for publication.

Rigolot called Hoffmann "an invaluable teacher” and his work "erudite and imaginative."

"Long before 'francophone' literature became fashionable, Hoffmann studied Haiti with an unparalleled understanding of its culture and wrote a remarkable series of publications," Rigolot said. From 1984-94, under a grant from the Ford Foundation, Hoffmann recorded and microfilmed selected periodicals from the libraries of Haiti. "This work of love saved thousands of documents that would otherwise have been lost to future generations of scholars," Rigolot said.

Hoffmann taught at Middlebury College's French Summer School for several years and at several universities in France.

He was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for Humanities in 1964. He also received fellowships from the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Ford Foundation and the American Philological Society. He served on many international boards and scholarly associations, and lectured around the world. He was the American correspondent for the prestigious Revue d’Histoire Littéraire de la France and the U.S. representative to the Association of French-Speaking Universities. In recognition of his services, he was awarded the prestigious Palmes Académiques by the French government.

Princeton University Library's Department of Rare Books and Special Collections houses the Léon-François Hoffmann Collection on Haitian Literature, a small file of correspondence (1990-2003) in French between Hoffmann and Haitian poet René Depestre (1926- ), including autograph letters, faxes, an annotated Chronologie Biographique and several other documents.

Throughout his time at Princeton, Hoffman participated in campus events and committees related to social justice. In 1968, he served on the Executive Committee of the University's Faculty Council on Vietnam; the committee telegraphed President Ho Chi Minh on April 2 of that year, urging the North Vietnamese head of state to "respond positively to President Johnson's de-escalation." In response to the 2010 earthquake in Haiti, the University held a Haitian Awareness Week, during which Hoffman gave a lecture about the political and social culture of Haiti.

His son Jacques Hoffman, the director of internships at Abraham Lincoln High School, a Title I high school in Brooklyn, New York, said, "My father transmitted to his children an unshakable ethic of racial equality and social justice."

Jacques Hoffman said his father "was an early proponent in the 1970s of providing more access to Princeton for people of color, frequently traveling to Brooklyn to interview students" and participating in Princeton's Special Freshman Orientation Program, designed to facilitate the transition from high school to college for minority students.

Jacques said his father completed his memoirs before his death, which include a story about his time as a Princeton doctoral student. Jacques recounted: "He and three colleagues, a Frenchman, Mexican and Chilean, drove to Mexico. Since they had extra space and little money, they advertised around campus to take on a fifth passenger: an African American who wanted to be dropped off in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Once in the segregated South, they realized that Jim Crow laws would prohibit them from eating and sleeping in the same establishments. They devised a scheme: they ordered in French and Spanish, pretending not to understand English. Eventually, flustered waitresses and managers gave up trying to explain the absurdity of not being able to serve their black colleague and they were often able to stay together."

His son Philippe Hoffman, a psychotherapist at St. Christopher's Inc., a residential facility for adolescents in Valhalla, New York, remembered spending time with his father on campus and in Princeton. "Some of my fondest childhood memories include walking through town to meet my father at his office before going to lunch at either the student center or the former Buxton’s diner on Nassau Street for hamburgers and milkshakes. He once offered me some sage words of advice: 'Don’t fight. But if you have to fight, fight to win.' This advice would come in handy a few times while resentfully having to attend summer camps in France as a kid."

During his half-century career at Princeton, Hoffmann served as director of graduate studies in his department and director of the Program in Latin American Studies.

Keith Walker, a 1977 graduate alumnus, credits Hoffmann with sparking his "passion for 19th-century French literature, for all things Haiti, and for the genius of the literary, political and cultural revolution that was the generation of Aimé and Suzanne Césaire from French Martinique."

Walker appreciated Hoffman's "marvelously destabilizing sense of humor, wit, irony, intelligence and affection that always spurred me on to better thinking, research and writing in both English and in French."

In the 1980s, Hoffmann founded a French-speaking theatrical troupe, "Les Chers Collègues," which staged plays and poetry recitals on campus. Later, this pioneer work became an important feature of the department under a new name, L’Avant-Scène, now directed by Florent Masse, senior lecturer in French and Italian.

Hoffman is survived by his wife, Anne; two sons, Jacques and Philippe, and their families.

Contributions in his memory can be made to Amnesty International or to Doctors Without Borders.

A "story-sharing gathering" will take place on campus at the end of September.

View or share comments on a blog intended to honor Hoffman's life and legacy.