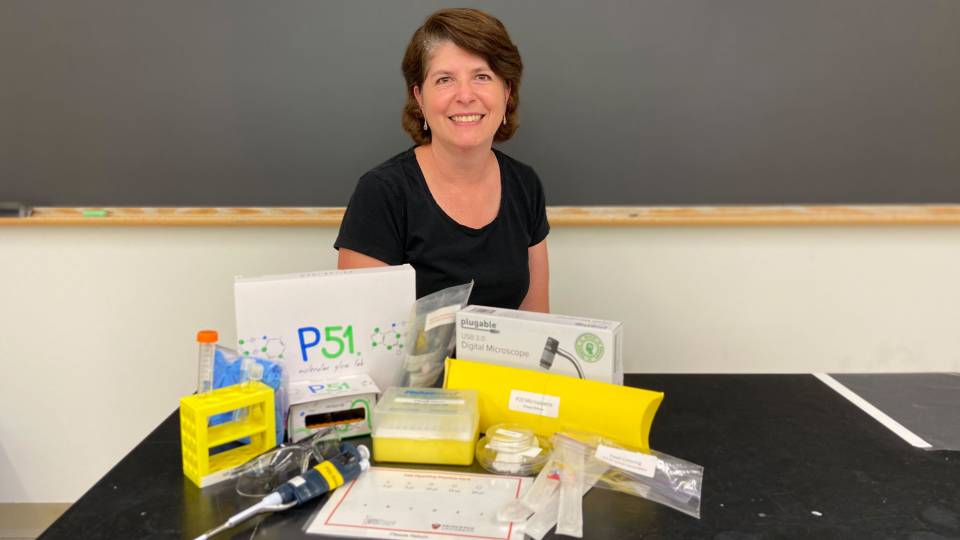

A framed photo of James Collins Johnson, a former enslaved man who worked on campus for more than 60 years until his death in 1902, stands front and center at an Oct. 22 ancestral remembrance ceremony in the easternmost arch of East Pyne Hall, which has been named for Johnson.

Many Princeton students and others pass through the two arches and courtyard of East Pyne Hall daily, but on Monday afternoon foot traffic — and time — stopped for a special public ceremony to honor James Collins Johnson, a former enslaved man who worked on campus for more than 60 years until his death in 1902.

Johnson’s story was unearthed as part of the Princeton and Slavery Project, which explored the ties of early University trustees, presidents, faculty and students to the institution of slavery. In April, the trustees accepted recommendations to name the easternmost arch in East Pyne Hall for Johnson. A formal dedication of the arch is planned for later this fall.

The idea for the ancestral remembrance ceremony — a sacred ritual rooted in African dance, music and prayers that pay homage to the spirit of ancestors — was initiated by Dyane Harvey-Salaam, a lecturer in dance in the Lewis Center for the Arts. Students in her fall course, “The American Dance Experience and Africanist Dance Practices,” performed a dance preceded by the ritual, led by Chief Ayanda Clarke, a New York-based master percussionist and highly respected Babalawo (spiritual leader) initiated into Ifa in Yorubaland, Nigeria, who is a frequent guest lecturer in Harvey-Salaam's class.

Harvey-Salaam said that when she learned about the depth of the Princeton and Slavery Project, she began to search for ways to become involved. "James Collins Johnson’s story became a beacon in that it provides an opportunity for me to contribute in a deeply spiritual manner as well as create a richer experience of cultural practices common in the African diaspora," she said.

Johnson was a fugitive from Maryland who arrived in Princeton in 1839 and worked as a janitor until 1843, when he was recognized by a student who alerted his previous owner, who had him tried as a runaway slave. After the trial, a local woman named Theodosia Prevost, a great-granddaughter of John Witherspoon and a granddaughter of Samuel Stanhope Smith, both Princeton presidents (who were both slaveowners) paid about $500 for his freedom, and students of the college took up a collection that raised $100 to help him start a business. He opened a used clothing and furniture store on Witherspoon Street and obtained the right to sell snacks on campus. When Johnson died, alumni and students purchased a headstone for him in Princeton cemetery, and inscribed an epitaph that described him as “the students friend.”

In recommending the arch be named for Johnson, the Council of the Princeton University Committee (CPUC) Committee on Naming said “we believe his story should be brought to the attention of future generations of Princetonians by associating his name with an arch that looks out on the places where he befriended students and sold his wares, but also one that looks out at the statue of John Witherspoon, one of the first nine Princeton presidents, all of whom were slaveholders at one point in their lives. Johnson’s experiences with Princeton students, both being turned into authorities as a fugitive (slave) and being befriended and defended, reflect the complex history on our campus with African Americans and with the institution of slavery.”

Chief Ayanda, dressed in white attire, marked the beginning of the ceremony with a libation (offering of water) and prayers, accompanied by the playing of the talking drum (DunDun), slung over his shoulder, its rhythmic tones creating a song punctuated by the jingling bells attached to both ends of the drum’s edge. He was accompanied by several members of the Fadara Group, including his father, Chief Neil Clarke, also a master percussionist and Elder Babalawo. The group produces events, performances and lectures focused on communicating the relevance and value of traditional African philosophies in today’s world.

At the center of the ritual space under the artch was a large framed photo of James Johnson, draped in green and gold fabric, set on a raffia mat on the stone floor of the arch, with a vase of white flowers and a trio of glass votive candles next to the picture.

"This is a dream that has come true for me," said Harvey-Salaam, saying how much the story of Johnson had moved her.

Chief Ayanda Clarke, a New York-based master percussionist and Babalawo (spiritual leader), opens the ritual with a call-and-response.

Chief Ayanda explained the meaning behind the ceremony, calling on "ancestors who can galvanize community to restore honor where honor was lost," and inviting the audience to make a circle and "lend your energy" to the proceedings.

"We're standing on the shoulders of James Johnson," he said.

As Chief Ayanda spoke of the importance of acknowledging one's ancestors, Harvey-Salaam lit a long candle taper from the main candle and in turn lit the small votive candles that each student carried as they approached the photo of Johnson one at a time. Each student spoke aloud a short homage of thanks to an ancestor in their own past. "I thank my great-grandfather for keeping my grandfather alive for two years during the Holocaust," said one student. Another thanked "my Great Aunt Nora, born out of wedlock in Ireland ... for introducing love when the world wanted to hate." And another spoke of her great love for her ancestor in Yoruba, the language of her country (Nigeria).

"Why ancestors?" said Chief Ayanda. "We couldn't be here but for our ancestors. ... This is not an African American story but a human story ... of everyone who overcame adversity so that we may be here today." He repeated the chant of "Ibase," explaining its meaning as "I pay homage," until the audience were all chanting in unison: "Ibase, James Collins Johnson, Ibase," first loudly, then gradually dropping into a soft whisper.

Students in Dyane Harvey-Salaam's fall course, “The American Dance Experience and Africanist Dance Practices,” perform a dance in East Pyne courtyard following the ceremony, which they had choreographed as part of the class.

The dance the students performed in the courtyard following the ritual was crafted during class as a way to celebrate the conclusion of the ceremony. Harvey-Salaam said the ceremony was designed to "uplift the space" in the arch, "giv[ing] it a special profound value by recognizing and honoring this man and his unique gifts in the arch that will carry his name."

Accompanied by musicians whose artistry serves as accompaniment during class sessions, the student-dancers, in two groups, created intertwined patterns as they leapt and ran diagonally across the courtyard, their arms wide and gesturing, their smiling faces turned up toward the bright sunshine. Ending the dance in a tight circle, they bowed toward one another, then turned and sprang back into action, running and reaching their arms toward the audience, inviting them to join in an improvised, joyful dance and clapping to the thunderous song of the drums.

As the dance reached its end, Harvey-Salaam, gesturing wide to indicate her thanks to everyone, said: "It is done. That arch will never be the same. ... Thank you all for coming and sharing."

Harvey-Salaam said she hopes the experience of preparing for and performing the ritual will have a lasting outcome for the students. "Along with pedagogical musings and intense physical demands, students [are] involved on a more intimate level. This hopefully will open other areas of sensitivity, interest and introspection relating to the course and life in general," she said.

Harvey-Salaam’s course introduces students to American dance aesthetics and practices, with a focus on how its evolution has been influenced by African American choreographers and dancers. The class centers on study of movement practices from traditional African dances and those of the African diaspora, touching on American jazz dance, modern dance and American ballet. Work in the dance studio is complemented by readings, video viewings, guest speakers and dance studies.

In a news release about the event, Clarke, a Grammy Award-winning musician, arts educator and lecturer, said the ceremony serves "to remind us all of [Johnson's] humanity, and to respect the contributions that he made to this community. Despite all odds, this man of African ancestry valued the principles of friendship, kindness and good character. In the ancient African spiritual tradition of Ifa, being a human being of good character is a mandate," Clarke said. "So, it is with this understanding that I come to honor the spirit of iwa pele (good character) and to say thank you to the spirit of Mr. Johnson, whose life is a light to us all.”