From left: Jacobus Fellows Pasquale Toscano, José de Jesús Montaño López and Geneva Smith stand with Dean of the Graduate School Rodney Priestley. Ryan Unger, not pictured, is shown below.

José de Jesús Montaño López, Geneva Smith, Pasquale Toscano and Ryan Unger have been named winners of the Porter Ogden Jacobus Fellowship, Princeton University’s top honor for graduate students.

The Jacobus Fellows will be honored at Alumni Day ceremonies Saturday, Feb. 24.

The fellowships support the students’ final year of study at Princeton and are awarded to one Ph.D. student in each of the four divisions — humanities, social sciences, natural sciences and engineering — whose work has exhibited the highest scholarly excellence. All four fellows plan to pursue academic careers.

José de Jesús Montaño López

José de Jesús Montaño López

Montaño López, a sixth-year doctoral student in the Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering who came to Princeton in 2018, earned his bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the National Autonomous University of Mexico in 2018.

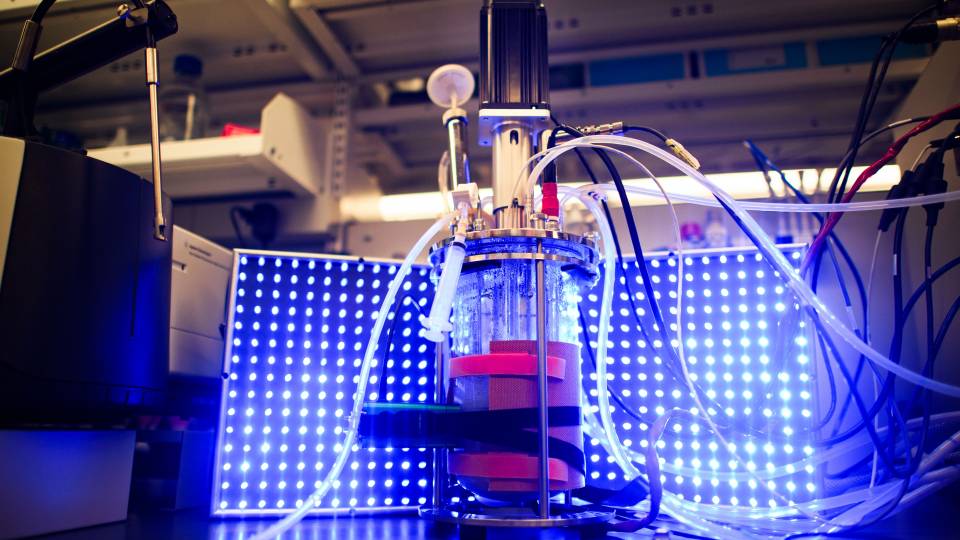

His multi-faceted research has already led to several papers in major journals, all focused on using yeast — the same yeast used for thousands of years to bake bread and ferment wine and beer — to produce isobutanol, a biofuel with the potential to replace both gasoline and jet fuel. His dissertation, “Systems Metabolic Engineering for Isobutanol Production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae,” details his efforts toward his goal of improving yeast biofuel production to curb global climate change.

“Compared to bioethanol, isobutanol has higher energy density, it is less corrosive, it can be compatible with current infrastructure for cars and can be upgraded to jet fuel,” said Montaño López. “And we can produce it through microbes! We feed the microbes any sort of natural sugar and they can produce this biofuel, which can reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the transportation sector and move us toward a more sustainable world.”

In his application for the Jacobus Fellowship, he wrote, “I have always been proud to belong to the Mexican Zapotec community, as it has forged a deep sense of respect for my cultural legacy and traditions. However, being Indigenous also frequently implies being exposed to pressing societal needs, such as the lack of equitable access to basic commodities, which constitutes the main motivation for my career.”

His adviser José Avalos, highlighted the need for biofuels and chemicals produced with biotechnology as part of moving away from fossil fuels. “You cannot electrify the transportation sector fast enough to prevent catastrophic increases in global temperatures by the end of the century, so we need biofuels to complement electrification,” said Avalos, associate professor of chemical and biological engineering and the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment. “You also cannot easily produce petroleum-generated resins or pigments with electricity. We need alternative sustainable solutions to replace petroleum. And biotechnology is that solution, because it has the chemical diversity to produce many different molecules from renewable resources as opposed to fossil resources.”

Avalos described Montaño López as a true artisan, in the best sense of the word. “Artisanal work requires a love for what you do that goes beyond technical aptitude. It also requires being very methodical and caring deeply about doing your best work every day, so that you end up with a beautiful piece of art — or in José’s case, this powerful strain library — that shows the months and years of dedication.”

With meticulous and painstaking work, Montaño López has generated a library of 5,000 genetically modified strains of S. cerevisiae, cataloged by their ability to produce isobutanol.

Avalos praised Montaño López for his unique combination of persistence and outside-of-the-box thinking. “Not just any student could do this kind of work. Most students would not have the patience or dedication to transform 5,000 strains, repeating the experiment more than 5,000 times — because you have to do them more than once — and then analyzing the results of 5,000 strains. I think he’s very bold in taking new approaches to old problems without knowing what he will find at the end. That takes a lot of courage.”

Among his many honors, Montaño López most recently won the top prize for renewable energy from the “Prototypes for Humanity” prizes awarded at COP28 in Dubai. During his first year at Princeton, Montaño López was honored with Mexico's 2018 National Youth Award, the highest honor given by the government to its citizens under 30 years old. He also received the Gabino Barreda medal, awarded by the 350,000-student National Autonomous University of Mexico to the student with the highest GPA in his graduating class. At Princeton, he has worked as an assistant for instruction in “Fundamentals of Biofuels and Chemical Reaction Engineering,” including helping students transition to online learning in the spring of 2020.

After graduating, he said, his would like his research to focus on the discovery and biosynthesis of complex plant natural products, including medicines, with the goal of more equitable access to medical treatment for all.

Geneva Smith

Geneva Smith

Smith, a sixth-year doctoral student in the Department of History who came to Princeton in 2016, earned her bachelor’s degree in anthropology and history from Columbia University in 2014. She took a leave during her Ph.D. studies to enroll at Yale Law School, crafting her own joint Ph.D./J.D. program.

Her dissertation, “Slave Courts and Compensation in the Eighteenth-Century British Atlantic,” examines the judicial system that exclusively tried the crimes of enslaved people in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Smith has built a massive archive of these court records that she unearthed in Pennsylvania, Maryland and Jamaica.

“Archives are spaces of mystery,” Smith said. “Each manuscript piece that I find, and each court case that I compile helps us paint a more complex and richer picture of what Black life was. I really got excited by the challenge of multiple historians saying, ‘These records don’t exist.’ ‘There’s no way to tell this story.’ I think I just love going to archives and seeing the records and realizing not only are they there, but we can actually build out a really rich story with what exists.”

“As a Black woman who has been through the legal system and faced its inequalities, I am uniquely positioned to do legal-historical work,” she said.

Said her adviser Wendy Warren, associate professor of history, “It’s important to underscore again the newness and consequence of this work: Because scholars had long believed records of these courts were lost, they had dismissed their importance.”

Her co-adviser Hendrik Hartog, Princeton’s Class of 1921 Bicentennial Professor in the History of American Law and Liberty, Emeritus, praised her as “the best researcher I’ve ever had as a graduate student” in his 45 years teaching at Princeton.

“Geneva is an extraordinarily talented young woman who managed to surmount quite terrible burdens in her early years,” he said. “She is strong-willed, stable, thoughtful and she has a good heart.”

He emphasized the extraordinary impact her work has had and will continue to have.

“Her results are transformative and will change the way historians write both the history of slavery in the Americas and the history of race in America,” Hartog said. “The amount of work it took for her to find these records is itself extraordinary. She found records that nobody knew existed, just by persistence, by imagination, by thinking about how to read records against what the label says they would say.”

He praised the “relentless determination” that carried Smith into more than 30 archives on three continents as she deciphered and preserved thousands of crumbling, handwritten records. “She has a kind of ‘historian’s intuition’ that led her to the confidence to know that these records would exist if she just kept at it. I really admire it.”

During her time at Princeton, Smith worked on the Princeton and Slavery Project, coordinated the Colonial Americas Workshop and participated in the Black Graduate Student Caucus as well as the Graduate Women of Color Caucus. Next year, she will finish her final year at Yale Law School, where she has been the academics chair of Yale Law Women+, the academic development chair of the Yale Black Law Students Association, and a fellow in the Program for Reproductive Justice and Reproductive Rights.

Pasquale Toscano

Pasquale Toscano

Toscano, a fifth-year doctoral student in English who came to Princeton in 2017, earned his bachelor’s degree in English and classics from Washington and Lee University in 2016. He also earned two master’s degrees from the University of Oxford, one in English in 2018 and the second in classics in 2019.

His dissertation, “Stand and Wait: Dynamics of Dis/ability in the Greco-Roman Epic Tradition,” reevaluates six writers from different times and cultures — Ovid, Aelius Aristides, Edmund Spenser, John Milton, Olaudah Equiano and Phillis Wheatley Peters — each of whom, Toscano argues, attempted to renovate the epic tradition by finding new ways to represent impairment.

Toscano has written on disability both for other academics and for public audiences, appearing in The New York Times, Vox and The Atlantic as well as Disability Studies Quarterly and the Classical Receptions Journal, among others.

“It’s imperative to be concerned about disability for a number of reasons, one of which is that it’s the most fluid identity category of them all,” Toscano said. “Anyone, at any time, can become disabled walking out of the house and getting hit by a truck, as I did. …. On the intellectual side of things, disability is everywhere,” he continued. “This is one of the oldest categories of difference that literary authors are dealing with. Starting with Homer, "Gilgamesh" — to get a handle on any of these poems, we have to understand how they’re using and why they’re using disability.”

Toscano had four advisers: Jeff Dolven, professor of English; Brooke Holmes, the Susan Dod Brown Professor of Classics and director, Gauss Seminars in Criticism; Rhodri Lewis, a senior research scholar and lecturer with the rank of professor in English; and Nigel Smith, the William and Annie S. Paton Foundation Professor of Ancient and Modern Literature.

“Pascal’s dissertation is about the epic tradition, about the poems that follow on Homer’s "Iliad" and "Odyssey," cascade through Virgil’s "Aeneid," towards a whole list of later poems that celebrate the strength and ability of heroic warriors and their contributions to a national culture,” said Dolven. “It is a kind of poetry that has been important to nation-building and national imagination since it was first written. And Pasquale’s interest is in who’s left out of that heroic narrative, or what stories might these poems be telling about bodies that are less able than Achilles’s body?”

Holmes highlighted Toscano’s “singularly impressive portfolio of publications — seven (!) in press or already published — in addition to numerous conference presentations, and across a range of fields. It would hard to find a more accomplished graduate student in the humanities at this point in their career. Pasquale’s record is breathtaking.”

During his time at Princeton, Toscano has mentored students in several capacities, including advising as a resident graduate student at Whitman College and organizing a postgraduate professionalization event series. He has also co-designed and co-taught a course through the Collaborative Teaching Initiative, “Bodies & Belonging in Milton’s Epic Tradition”; taught incarcerated students through Princeton’s Prison Teaching Initiative; and served as the Graduate Action Committee academic chair and Working Group for Graduate Issues chair.

Among his many awards, Toscano received Princeton’s 2019 Centennial Fellowship and the 2022 Harold Grim Prize, the latter awarded annually by the Sixteenth Century Society and Conference for the best article on the Reformation published in 2021. After completing his Ph.D., Toscano will join Vassar College as an assistant professor in the English department.

Ryan Unger

Ryan Unger

Unger, a fifth-year doctoral student in mathematics who came to Princeton in 2019, earned his bachelor’s degree in mathematics from the University of Tennessee in 2019.

In his dissertation, “Gravitational Collapse to Extremal Black Holes and the Third Law of Black Hole Thermodynamics,” Unger successfully disproved the third law of black hole thermodynamics established in the 1970s.

“The third law says that a black hole cannot get to zero temperature in finite time,” Unger explained. “In my thesis, I precisely described a process which allows a black hole to form and then cool down to zero temperature in finite time, which disproved the third law.”

He disproved the law “completely by accident,” he said, while tackling a related black hole problem that his adviser, Mihalis Dafermos, had assigned him. “Christoph [Kehle], my collaborator, and I, we worked on that problem, and we were able to solve the problem that he gave us. But then without telling Mihalis, we just started trying to push a little bit further. And last summer, we figured out, ‘Oh, it’s actually not that difficult to just make a zero-temperature black hole.’ We told him this, and he got very excited and sent me like 10 papers and said, ‘Read all these papers, find out why they were wrong.’”

Dafermos described Unger’s work as “absolutely spectacular” and “truly exceptional,” saying that, “in my opinion, it represents perhaps the most unexpected (and potentially the most impactful) contribution of mathematics to our understanding of general relativity that I have seen in at least the last five years.”

The mathematics professor emphasized, “The third law did not fall on the basis of some technicality. Ryan’s work shows that it is false both in letter and in spirit.”

Dafermos said that most Ph.D. work in mathematical physics involves rigorously proving something already theorized. “What’s different about this, and what’s rare, is when you prove that they had it all wrong. Remarkably, this is exactly the case with this third law. It was simply incorrect.”

Since coming to Princeton, Unger has given 19 invited talks while also serving as a precept instructor for “Calculus I” and an assistant in instruction for “Calculus III,” “Linear Algebra,” “Real Analysis,” and “Partial Differential Equations.” During the 2022-2023 school year, he was a visiting student at the University of Cambridge Department of Pure Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics. After completing his Ph.D., he will be a National Science Foundation Postdoctoral Fellow at Stanford University and a Miller Fellow at the University of California-Berkeley.