January 28, 2004: Features

|

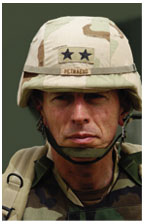

Photo: U.S. Army |

Our

Man in Mosul

David Petraeus

*87 got an Iraqi city running again after the war, but tougher

challenges may lie ahead

By Joshua Hammer ’79

On a crisp November day in northern Iraq, Maj. Gen. David H. Petraeus *87 touches down in a Blackhawk military helicopter in a cloud of dust, and hustles across the landing strip for an inspection tour. Arms bent at the elbows and swinging forward and back, nine-millimeter pistol fitted snugly in a black leather holster strapped to his thigh, the 50-year-old commander is a picture of jaunty confidence as he sweeps past welcoming U.S. soldiers toward a gravel parade ground. Thirty crisply uniformed Iraqi officers, a mix of Kurds and Arabs, stand rigidly at attention. This is the new Iraqi Civil Defense Corps, a homegrown security force that someday may replace the U.S. occupation troops as keepers of the peace in Iraq. Petraeus, commanding general of the 101st Airborne Division, came up with the concept for the corps back in May, shortly after occupation chief L. Paul Bremer disbanded Iraq’s army, sending hordes of disgruntled fighters into the streets without jobs. Proactive, and sometimes dismissive of the hidebound bureaucracy in Baghdad, Petraeus constantly is searching for ways to keep Iraq’s reconstruction on track. “I want to ramp up the Arab contingent [in the defense corps]. We’ve got to be sensitive to that,” he tells a subordinate. Then, on the spot, he orders up another training class for Iraqi noncommissioned officers, despite growing constraints on his budget. “I know we’re short on money. But let’s go ahead and take the risk. Just figure we’ll find the cash.”

Beneath Petraeus’s self-assured exterior, however, lies a deepening sense of concern. Just one day earlier, Iraqi insurgents shot down a Blackhawk helicopter near Tikrit, killing four U.S. soldiers from Petraeus’s division; a few hours later an improvised explosive device blew up beside a passing convoy in Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city, killing another of his men. After a four-month lull during which Petraeus didn’t lose a single soldier in combat, the Screaming Eagles had suffered five fatalities in the last 24 hours. “To shoot a helicopter out of the sky with a rocket-propelled grenade – that’s not an easy thing to do,” Petraeus tells me as we step back into the chopper after the ceremony. “They’re getting more sophisticated, and they’ve had a bit of luck.”

The stakes in Mosul are enormous. For months, this ancient citadel on the Tigris River, home of two million Kurds, Arabs, and Turkmenis, had been hailed as Iraq’s model city, with thriving shops and businesses, a functioning local government and police force, and a low crime rate. In sharp contrast to Baghdad and the Sunni heartland, Iraqis largely welcomed the American forces, and – until recently – the troops could walk unmolested through the streets at night and mingle with the locals. U.S. officials and Iraqis alike say much of the credit belongs to Petraeus, a bureaucracy-busting, hands-on, career military officer who received his doctorate from the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. “He excels as both a military commander and a civil administrator,” says Amer Abu al-Daoud, a member of Nineveh’s provincial council.

By the fall, however, the wave of attacks on American soldiers in Mosul, as they sought to root out Iraqi insurgents, was presenting Petraeus with his greatest challenge. Petraeus had hoped that the killing of Saddam Hussein’s two sons in July would take the life out of the insurgency, but after a brief dip in the violence, the attacks began anew with startling ferocity and continued even after the capture of Saddam Hussein last month. Military and counterterrorism experts in Iraq say Petraeus has done the best job possible, though they acknowledge that his crackdown on suspects recently has created some ill will among the population. And money used to jump-start projects in earlier days is running out.

Petraeus brings both intellectual heft and a career soldier’s sense of discipline to his job. The son of a Dutch merchant marine captain and a mother from Brooklyn, he grew up in Cornwall, New York, a few miles from West Point, and graduated from the military academy in 1974. As a captain in the Army, he spent two years at the Woodrow Wilson School, earning a master’s degree and, after he returned to West Point and wrote his dissertation, a Ph.D. His dissertation dealt with the United States and the lessons of Vietnam; Petraeus argued that America’s failure there made the nation reluctant to use force in other engagements – “a thesis,” he says, “that was reinforced by what happened in Somalia.” In the 1990s Petraeus served in Bosnia and Haiti as part of NATO and American missions, where he got his first experience in nation-building, and was executive assistant to Gen. Henry H. Shelton when he was chairman of the joint chiefs of staff. Married, with a son and a daughter, Petraeus is a marathon runner, a parachutist, and an all-around fitness fanatic who challenges his soldiers to spontaneous push-up contests, which he invariably wins.

Petraeus evinced little reluctance to use force during the 101st Airborne’s drive through Iraq in the first days of the war. After fierce fighting with Saddam Hussein’s fedayeen around Mosul and Karbala, the general and his troops swept into Baghdad in mid-April; in early May they moved north to Nineveh Province, and its major city, Mosul. Petraeus had three priorities: to establish security in the city; to get schools, hospitals, businesses, and basic services running again; and to create a rudimentary governing structure made up of Iraqis. Setting up his headquarters in Hussein’s looted palace on a hilltop overlooking the Tigris, Petraeus began to make contact with leaders of the city’s Arab, Kurdish, and Turkmeni communities. “There was a power vacuum,” Petraeus says, over lunch in his second-floor office at the palace. (Its opulent marble floors and teakwood-beaded ceiling contrast with the spartan military cot in the corner where Petraeus spends his nights.) “Either we would fill the vacuum or the Iraqis would, and if we did it, it would be difficult to extricate ourselves.”

Petraeus established a pattern of bold initiatives that stood in stark contrast to the snail’s-pace progress that dragged down the rest of Iraq. He organized elections in May for a local governing council, the first to be set up in Iraq, and got his hands on $32 million in cash confiscated by the Coalition Provisional Authority from Hussein’s palaces. Petraeus earmarked the money for thousands of projects, including the reconstruction of Mosul University, irrigation schemes, the refurbishment of several idle asphalt plants, and a cash-for-electricity deal with Turkey that helped bring Mosul round-the-clock power. After Bremer disbanded the Iraqi army Petraeus set up a monthly stipend for 25,000 ex-soldiers, and thus helped keep frustration from boiling over into violence. In May he inaugurated both the Iraqi Border Police and the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps, which together employ about 10,000 former Iraqi troops.

Petraeus

often has found himself falling back on the lessons he learned at the

Woodrow Wilson School. Last May the general began paying the salaries

of government workers using millions of Iraqi dinars that he had recovered

from a Mosul bank. Thanks to his grounding in basic economics, he says,

he recognized the inflationary dangers of flooding the economy with cash

at a time when there was little merchandise available in the city. So

he got Syria to reopen its border, and truckloads of Syrian merchandise

began pouring into Mosul’s markets; the fear of inflation dissipated.

Petraeus’s political philosophy course at Princeton inculcated in

him an understanding of the basic rights of minorities, he says; these

are principles he tries to safeguard in balancing relations between the

province’s Arab majority and its Kurdish minority. He also brought

into the command structure several other graduates of the Wilson School,

including Col. Michael Meese *00 and Lt. Col. Richard Lacquement *00,

to privatize some of Mosul’s state-owned enterprises.

Petraeus

often has found himself falling back on the lessons he learned at the

Woodrow Wilson School. Last May the general began paying the salaries

of government workers using millions of Iraqi dinars that he had recovered

from a Mosul bank. Thanks to his grounding in basic economics, he says,

he recognized the inflationary dangers of flooding the economy with cash

at a time when there was little merchandise available in the city. So

he got Syria to reopen its border, and truckloads of Syrian merchandise

began pouring into Mosul’s markets; the fear of inflation dissipated.

Petraeus’s political philosophy course at Princeton inculcated in

him an understanding of the basic rights of minorities, he says; these

are principles he tries to safeguard in balancing relations between the

province’s Arab majority and its Kurdish minority. He also brought

into the command structure several other graduates of the Wilson School,

including Col. Michael Meese *00 and Lt. Col. Richard Lacquement *00,

to privatize some of Mosul’s state-owned enterprises.

After his inspection of the Iraqi Civil Defense Corps, Petraeus takes me on a helicopter tour of Mosul. As the chopper soars 2,000 feet over the city, well within range of shoulder-fired SAM-7 missiles, he points out the charred remains of the house where “number two and number three” – Qusay and Uday Hussein – were hunted down and killed in a furious gun battle. Petraeus, who may be the most accessible general in Iraq, admits to a rising degree of frustration with the media. “It’s hugely significant that America’s sons and daughters are dying, but it seems like that’s all that gets reported,” he tells me. “One hundred thousand soldiers are doing incredible things every day.” I ask the general if he remains optimistic about America’s mission in Iraq. “It’s doable,” he says emphatically. “It has to work.”

Then he casts another wary look out the Blackhawk window, high above

the warrens of the city where Mosul’s insurgents lie in wait. ![]()

Joshua Hammer ’79 is chief of Newsweek’s Jerusalem bureau and the author of A Season in Bethlehem: Unholy War in a Sacred Place (2003).