October 6, 2004: Features

Rumsfeld’s Princeton

A portrait of the defense secretary as a young

man

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83

Above: U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld ’54, surrounded by American military personnel, receives a Princeton cap from Army Major Virginia Woods Gerde ’89 at Saddam Hussein’s Al Faw Palace, May 13 in Baghdad. (David Hume Kennerly/Getty Images; Nassau Herald/Princeton University Archives)

Above, Rumsfeld when he was captain of the wrestling team. The Nassau Herald described him as a “speedy takedown specialist.” (1954 Bric a brac/princeton university archives)

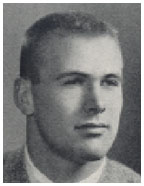

At graduation, Rumsfeld and classmates who had rooms together: Back row, from left, Dick Stevens, Joe Castle, Sid Wentz, Derek Price, Rumsfeld, and Prewitt Turner. Front row, from left, Somers Steelman, Peter Gall, and Michael Weatherly. (Courtesy Dick Stevens ’54) |

Those who admire Donald H. Rumsfeld ’54, and those who do not, tend to use some of the same adjectives to describe him – words to which different meanings can be attached, depending on one’s perspective. And while it can be a risky and facile undertaking to extrapolate the adult from the undergraduate, those who knew the U.S. secretary of defense well when he was a student at Princeton describe Rumsfeld the student in terms that would be familiar to anyone who watches him on the news today.

“Serious . . . and incredibly disciplined,” says Joe Castle ’54, who roomed with Rumsfeld for three years.

“He didn’t take any side streets,” says Sid Wentz ’54, speaking metaphorically of Rumsfeld’s approach to everything from sports to politics to interpersonal relationships. “He went right up Main Street.”

“He was very determined, very orderly. Very orderly,” echoes Dick Stevens ’54, emphasizing the word to make his point.

“With Rummy, right was always right,” says Somers Steelman ’54, explaining his ex-roommate’s sense of morality. “He was a great one for ‘What works?’” Steelman adds. “There was no esoteric thinking about ‘What could be?’”

Whatever one’s opinion of the Bush administration’s defense policy, Rumsfeld has pursued it with dogged determination, conviction of the rightness of his path, and a willingness to take on critics with ferocity. In the early days of the war on terror, Rumsfeld’s crisp press briefings won him admirers and even a mention in People magazine as one of the sexiest men in America (prompting an amused President Bush to dub the 72-year-old secretary a “matinee idol.”) But as the number of American casualties in Iraq continued to rise and news of scandals such as the abuse of Iraqi prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison have filled the papers, calls have been issued for Rumsfeld’s resignation (although the commission investigating Abu Ghraib rejected the idea). Today, Rumsfeld is the most controversial defense secretary since Robert McNamara, an uncompromising warrior to some, a symbol of administration hubris and miscalculation to others.

It is ironic that a man so self-directed in life ended up at Princeton almost by accident. A state wrestling champion at New Trier High School outside Chicago, Rumsfeld was recruited by several of the Big Ten schools but was persuaded to apply to Princeton by his principal and several other local alumni, including fellow New Trier students who had graduated a year ahead of him, Ned Jannotta ’53, Jim Otis ’53, and Brad Glass ’53. “Don was a good prospect,” recalls Jannotta. “At Christmas during our freshman year, a few of us went back home and collared him.”

The Rumsfelds were a middle-class family. Rumsfeld’s father, George, sold real estate but joined the Navy at the age of 38 shortly after World War II broke out, instilling in his son a lasting appreciation for government and military service as well as a deep sense of patriotism. The family moved frequently during the war before settling in suburban Chicago. Money was tight (“I can’t ever remember a time when [Donald] didn’t have a summer job,” his mother once told a reporter), and Rumsfeld recalls hitchhiking to Princeton to begin his freshman year.

Rumsfeld found the transition difficult, and not only financially. Having come from a public school, and a Midwestern one at that, Rumsfeld felt he was not as well prepared as Eastern classmates from more privileged backgrounds. “Back in my day,” he says, “an awful lot of people had gone to prep school, and the first year those people had taken most of the freshman courses by the time they got there. I hadn’t.” To compensate, Rumsfeld, who majored in politics, spent a lot of time in the library, adhering to a rigorously disciplined schedule. Stevens recalls Rumsfeld chiding his friends for wasting their time reading a daily newspaper. Just read the Sunday paper and a good weekly news magazine and you’ll get all the information on world affairs you need, he told them. “I worked hard,” Rumsfeld admits. “I was disciplined and I managed my time. I got up early and worked and went to class and went to sports, whatever it was that season. And I didn’t have any money, so I didn’t have dates or anything like that. I had no reason not to be highly focused.”

His self-assurance at Princeton manifested itself even in bicker sessions, which then were conducted in the rooms of the sophomores that the clubs had decided to visit. One night, Ivy Club members stopped by to bicker Rumsfeld, but he was uninterested in Ivy and made his feelings known. Rather than put on a tie, as was customary, he met the visiting upperclassmen “wearing this gray T-shirt, a towel around his neck, [and] his hair was wet,” Castle remembers. Rumsfeld and several of his friends later joined Cap and Gown; even there, where he hung out or shot pool during rare idle hours, he struck some members as aloof and unapproachable. “Donald Rumsfeld typified the kind of person who made me nervous at Princeton,” wrote a classmate, S. Barksdale Penick III, in a Class of ’54 reunion book. “He was a jock and popular. I didn’t know how to approach him.”

Most of the defining moments of Rumsfeld’s time at Princeton came outside the lecture hall – in athletics, where Rumsfeld says he learned that “there is a relationship between effort and application and results.” Although he captained the 150-pound football team, Rumsfeld enjoyed greater athletic success as a wrestler, starting with an undefeated record as a freshman. As a junior, he finished second in the Eastern Intercollegiate Wrestling Association in the 157-pound weight classification. Elected team captain for his senior year, Rumsfeld went undefeated again during the regular season and finished fourth in the Easterns.

It is in the wrestling room, more than anywhere else, that one can catch a glimpse of the mature Rumsfeld. Defeat in wrestling can be not only humiliating (being pinned to the mat in front of scores of spectators) but painful as well, and even the victor bears scars. “Rummy always had swollen ears and mat burns all over him,” Castle says. Once, in a match against Cornell, Rumsfeld separated his shoulder, yet continued and managed to win on points.

Although the Nassau Herald called him a “speedy takedown specialist,” that phrase does not adequately describe the Rumsfeld wrestling style. He was characteristically preemptive, refusing to wait for a chance to exploit an opponent’s weaknesses, preferring instead to initiate the action and make his opponent react to him. A favorite move was the “fireman’s carry,” in which the wrestler drops to one knee, shoots under his opponent’s leg, and throws him over his shoulder before dumping him on the mat. It requires quickness and strength, and Rumsfeld practiced it often in the wrestling room, as well as on his roommates.

In an era before the popularity of weight training and aerobics, most wrestlers built themselves by doing pull-ups, chin-ups, running, and simply wrestling. (Though certainly fit, Rumsfeld came in third in voting by his classmates for “Best Body” senior year, an underwhelming honor he has frequently invoked to poke fun at himself.) The most onerous part of a wrestler’s week came on Thursday before a Saturday meet, when the time came to be weighed. Wrestlers who failed to make their assigned weight could not compete that week. Like most of his teammates, Rumsfeld frequently spent several hours before weigh-ins wearing a rubber suit and running around the boiler room beneath Dillon Gym, trying to shed the last few pounds.

Rumsfeld was deceptively strong, something he learned to use to his advantage. “Word got around that Rummy could do one-armed push-ups, but no one knew how many,” says Steelman. Challenged one night, Rumsfeld got down on the floor and squeezed off 50 of them right-handed. Sensing a weakness, Dick Stevens threw a $5 bill on the floor and bet Rumsfeld that he could not do 50 more, this time left-handed.

“He did the 50, picked up the money, and left the room,” Stevens recalls.

With few exceptions, Rumsfeld recalls little about the courses he took as an undergraduate or the professors whose lectures he attended – members of a early 1950s faculty that he describes as “left of center.” He remembers two fondly: Professor Walter P. “Buzzer” Hall of the politics department, who tried to instill in students, as the Daily Princetonian put it, a “sort of 19th-century liberalism, [which] combines a fairly conservative political view with an unshakable belief in the greatest freedom of thought and expression”; and historian Eric F. Goldman, best known for his landmark social history of the Progressive Era, Rendezvous with Destiny (1952), which was published while Rumsfeld was at Princeton.

But Rumsfeld was more critical of others, remembering that he often questioned what professors said in class and “you wonder whether what you’re hearing is the whole story.” Decades later, he singles out Professor Harper Hubert Wilson of the politics department, a self-described “conservative, anarchist, and socialist” whose course Political Power in the United States was designed, according to a description in the Princeton archives, “to shock and stimulate students to be aware of the problems of power and dissent in American political life.” On one occasion Wilson lectured students about corruption in business, advancing what Rumsfeld recalls as a faith in government to solve problems rather than the private sector. Rumsfeld’s characteristic response was to ask his father, who served on the ethics committee of the local real estate board, for a real-world perspective on the problem. “I felt I learned as much or more from my peers and my individual study as I did from the faculty,” he says. “Maybe that’s a good thing. Maybe it’s designed to be that way.”

Indeed, Rumsfeld’s views on government and America seem to have been shaped outside the lecture hall – by his father’s example, by conversations with his friends, and by his participation in Naval ROTC, which required him to attend training classes during the summers and three times each week. (Rumsfeld joined the Navy after graduation, serving as pilot and flight instructor.) Notwithstanding a boyhood fascination with Franklin Roosevelt, Rumsfeld says he was not politically active as an undergraduate. Still, he remembers avidly watching with his friends the Army-McCarthy hearings in 1954, the climactic showdown between the red-baiting Wisconsin senator and the military officials he accused of coddling Communism. “We were just glued to it. It was so dramatic,” he recalls. Asked for whom he was rooting, Rumsfeld blurts, “Oh, the Army! McCarthy – you just couldn’t imagine his behavior, his manner of treating people and the seeming unfairness of it, the bullying.”

Though the Korean War ended in 1953, a very different turning point in foreign affairs dominated Rumsfeld’s senior year, when the French force in Vietnam surrendered at Dien Bien Phu. Castle vividly remembers showing Rumsfeld a newspaper photograph of an exhausted French legionnaire on the dock at Marseilles being spat on by angry citizens. The idea of a soldier being condemned by his own countrymen seemed appalling to Rumsfeld. “That could never happen here,” he insisted to his friend.

Rumsfeld says he was inspired by an idealistic address given by Adlai Stevenson ’22 at the class’ senior dinner in the winter of 1954. Stevenson called on the members of the class to apply their education to the nation’s service. “You dare not withhold your attention,” Stevenson exhorted them. “For if you ... do not participate to the fullest extent of [your] ability, America will stumble, and if America stumbles the world falls.”

“I found [the speech] enticing and appealing in a way that made anyone who had any interest in that subject more interested,” says Rumsfeld, who still quotes passages from the address half a century later. “If you enjoy doing things where you feel useful and where you feel they’re important, clearly being part of this country’s government is particularly central to what’s going on in the world.”

Rumsfeld was so moved that for years afterward he sent copies of Stevenson’s speech to friends and acquaintances. (The class recently republished the speech in its 50th-reunion book.) He believes Stevenson’s call for participation in public affairs is no less vital today. “Democracy is tough and it turns a lot of people off – the untidiness of it, the challenges of it. There are a lot of people who don’t like the conflict that’s inherent in it. For the system to work, people have got to think and read and try to understand and engage and participate.” He clearly scorns those who feel otherwise. “There are people who think that being independent and apart from it are admirable. You have a little halo over your head and you’re not a partisan and not engaged in it because it’s grubby,” he says.

Rumsfeld’s senior thesis concerned President Harry Truman’s seizure of the nation’s steel mills in 1952 in response to a strike, and the Supreme Court’s subsequent decision striking the act down as an abuse of executive power. In his conclusion, Rumsfeld endorsed the Court’s decision to curb the president’s emergency powers.

“There is much to be said for not tying the hands of the President unduly,” he wrote. “No one wishes to injure adequate defense action in the event of an enemy attack or an emergency of similar gravity. But, it must not be forgotten that the concept of emergency is elastic.”

That may have been the realist writing, but Rumsfeld went on to embrace the philosophical underpinnings of the Court’s decision, as well. Observing that, in America, almost anyone could rise to the presidency (something he saw as a mixed blessing), Rumsfeld concluded by quoting Jefferson: “With an eye ... [that] the Presidency may not always be occupied by a man intelligent enough to use his power sparingly, Jefferson had the correct answer 165 years ago, when he warned: ‘In matters of power let no more be said of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.’ Let us be thankful that we live in a land where we can demand of those in authority, ‘Give us an account of thy stewardship.’”

Rumsfeld has remained particularly close to his old Princeton roommates, all of whom still pose for a group photo at each major reunion and, at Rumsfeld’s suggestion, get together to mark their major birthdays.

Those school ties have helped keep Rumsfeld grounded, sometimes whether he wanted it or not. Steelman recalls a time, shortly after Rumsfeld was elected to Congress, when the old friends visited him in Washington. Rumsfeld gave the group a rather stilted tour of the Capitol.

“He sort of treated us like constituents,” Steelman recalls. “So we started planning how we were going to get him down to being a roomie again.” They seized their opportunity that evening. During a touch football game in Rumsfeld’s backyard, they tackled the young congressman, pinned him to the ground, stripped off his pants, and threw them up in a tree. “That got everything back onto an even keel,” Steelman laughs.

Rumsfeld achieved some measure of revenge a decade later when he served as chief of staff to President Gerald Ford. Castle and a few others again were visiting Washington and were being taken through the West Wing of the White House by an aide when Rumsfeld and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger emerged from the Oval Office. Castle says that Rumsfeld saw him, grabbed him in a fireman’s carry, and dropped him to the carpet as startled Secret Service agents drew their guns.

“Must be one of your Princeton friends,” Kissinger remarked.

![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.