|

|

January 25, 2006: Features

The

Producer

The

Producer

Roger S. Berlind ’52: A life in theater

By Annalyn Swan ’73

Illustration by Michael Witte ’66

Everyone knows what Broadway producers are like, right?

The cigar-chomping wheeler-dealers of the 1930s movies, their hands permanently glued to the telephone. The frenetic duo of 42nd Street, trying to salvage their show before it craters. Nathan Lane’s down-on-his-luck, looking-for-a-buck schemer in the wildly successful The Producers.

So how to explain Roger S. Berlind ’52 — producer, philanthropist (responsible for McCarter’s Berlind Theatre), art collector, and a man who doesn’t fit the Broadway mold in any conceivable way? Soft-spoken and courtly, with an impish sense of humor that begins to sparkle when you least expect it, Berlind seems like a throwback to the Princeton man of Jimmy Stewart ’32’s day — “such a gent,” Michael Cadden, the director of Princeton’s Program in Theater and Dance, calls him. Instead of occupying a cramped space on 42nd Street, Berlind’s office is in a 30th-floor suite in Manhattan’s 50s, with drop-dead views over Fifth Avenue and to the Hudson in the distance. It’s elegant and sleek, like the stage set of a Noel Coward play. There is no incessant ringing of phones, no untidy piles of Playbills and scripts, no last-minute crises.

And yet, Berlind has risen to the top of one of America’s most risky, volatile, and shark-infested professions. Over the course of 30 years and 50-plus shows, Berlind has had his fair share of critical and popular successes, with 13 Tonys and one British Olivier Award lined up to prove it. His past winners have included The Real Thing; Kiss Me, Kate; and City of Angels. Recently, there were the Pulitzer Prize-winning Proof and Doubt, both major hits. And in a world fabled for feuds, fallouts, and titanic egos — epitomized by the three Shubert brothers, who ran roughshod over actors, unions, and the competition to found their theater dynasty — Berlind has achieved all this and still gotten along with everyone. “His integrity is unquestioned,” says Rocco Landesman, a longtime producer and sometime-partner of Berlind. “I can’t think of anyone who is more respected.”

Berlind is the first to say that making a living as a Broadway producer is a “notoriously hazardous business.” “I’m doing it because I love it,” he once said. “There is not an activity I can think of that wouldn’t be more remunerative, but I love theater. It is addictive.” That love is apparent from the pride he takes in walking a visitor past posters of Broadway shows that he has produced. They line the hall and foyer in his office — decades of showbiz history at a glance. Berlind gestures fondly at this poster and that one, sounding like a devoted parent showing off the children. There are the triumphs such as Amadeus — “my first big hit.” And then there are the flops. “Getting Away With Murder — that got killed by critics,” Berlind says. “It opened and closed in two weeks. I had a great time coming up with an advertising campaign for the closing of the show. The ads had a gargoyle in them, and I had the gargoyle point his gun at his head. And the last headline read, ‘Goodbye, cruel world.’”

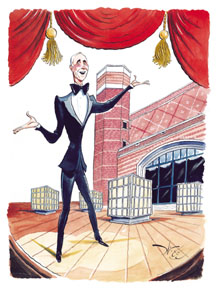

Michael

Cadden, director of the Program in Theater and Dance, left, and Roger

S. Berlind ’52 at the opening of the Berlind Theatre in September

2003. (George Vogel) Michael

Cadden, director of the Program in Theater and Dance, left, and Roger

S. Berlind ’52 at the opening of the Berlind Theatre in September

2003. (George Vogel) |

As Berlind’s wall of posters attests, even the most seasoned producer cannot predict success. Recently, there was the much-written-about production of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? with Kathleen Turner and Bill Irwin. Despite the respectful attention, it was not a box-office hit. While Sophisticated Ladies was an enormous winner, Passion, a Stephen Sondheim musical, was not. And Berlind still can’t figure out why Steel Pier, a musical that was a favorite of his, wasn’t a success. “It never found its audience,” he says with a shrug. From his earliest years, Berlind was a child with a wide array of talents. He loved music — especially songs — and could play the piano by ear. “I remember when I was 10, listening to Harlem stations and hearing Billie Holiday,” he says. “Jazz was a passion. I used to save up and buy the latest Victor or Decca records of Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Glenn Miller. And I knew the entire Rodgers and Hart canon.” He grew up in Woodmere, N.Y., the second of four sons. His father was a hospital administrator (“no artistic instincts at all”); his mother was a painter who studied at the famed Art Students League in New York City. From the age of 11, his parents allowed him to go into Manhattan on weekends to the old movie houses on Broadway. “There was the Paramount and the Strand and the Victoria,” recalls Berlind. “They had stages and big bands. You’d see a movie and then a stage show.”

In 10th grade, he began to act. By then, he had left public school for Woodmere Academy, a highly regarded local private school. There, the classics teacher, Rolfe Humphries, made a lasting impression. “He had a face like a fierce skull,” recalls Berlind. “He used to end every class with a reading — from Shaw, from Shakespeare. But he had also been an All-American football player at Amherst and he would scrimmage with the guys. I was in awe of him. He taught me that learning was not a sissy thing.”

Berlind — himself something of a scholar-athlete — played football, basketball, and baseball, won the school’s math prize, and edited the school paper. He was also head of the dramatic society and acted in virtually every play at Woodmere. What he enjoyed the most, however, was songwriting. “I wrote some material for our big annual musical at Woodmere,” he says. “The songs were all original. And I wrote both the music and lyrics for my class song.”

He stops suddenly, looks a trifle embarrassed, and then says, “Want to hear it?” He heads to the upright piano that sits just outside his office. He plays a few bars, then sings, in a charming, slightly tentative voice: “The hour has come, when we must say goodbye/and leave your friendly halls at last... .” His hands seem completely at ease on the keyboard. “I never had piano lessons,” he says. “But I always seemed to understand the harmonic structure of a song automatically.”

At Princeton, Berlind, an English major, kept up with musical theater. He joined Triangle, for which he also wrote songs. Not surprisingly, after graduating and doing a tour of duty with the Army, he tried his hand at songwriting. It was a difficult path, and Berlind was forced to return to his parents’ home in Woodmere before acknowledging defeat. “I took the advice of a good friend who said that Wall Street was popping,” says Berlind. He gave finance a try, only to discover a striking aptitude for it. “I really loved analyzing companies and making presentations to institutions about why such-and-such was undervalued,” says Berlind. “The intellectual challenge of it.”

Many people who have met Berlind in the past 25 years don’t realize that he was once one of the most innovative bankers on Wall Street. In 1960, only eight years out of Princeton, he formed a new securities firm — Carter, Berlind, Potoma, and Weill — with three other young brokers, brashly taking on the older, august firms on the Street. They specialized in all the “newer” forms of finance that reached their apogee in the 1990s — mergers and acquisitions, venture capital deals, institutional research.

Far from mimicking the traditional white-shoe investment houses, the young partners created a refreshingly iconoclastic model, working together in the same office. Several years later, the firm became Cogan, Berlind, Weill & Levitt and, by 1970, it employed close to 400 people. It was a stellar lineup of talent: The Weill from that original firm was Sandy Weill, future chairman of Citigroup; the Levitt was Arthur Levitt, future chairman of the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Berlind was the firm’s first CEO, a position he assumed after the firm grew too unwieldy for all the partners to function equally any more. He was then only 39 years old. Of the supercharged group, he was the most unlikely choice by far, both by background and temperament. But that was the point. He was known as the voice of reason and compromise, and could provide a diplomatic buffer between the big egos. Berlind remained the CEO for three years as the firm acquired other firms at a dizzying rate. In 1973, however, power shifted, and Berlind became vice chairman of the board. Doubts about the ruthlessly ambitious aspect of Wall Street, which went all the way back to his first job on the Street, resurfaced in his mind. “At Eastman Dillon, the first firm that I worked for, they gave every prospective employee two tests,” Berlind recalls. “One was for intelligence, the other for personality. So I took them and the guy called me in again. He said, ‘I don’t know what to make of this. You have one of the highest scores that anyone has ever gotten on the intelligence test. But’” — here Berlind chuckles — “‘your personality profile indicates that you’re practically dead. No motivation at all. There’s no hope.’” Berlind pauses and says, “The funny thing is, he was right.”

By the middle of 1975, Berlind was heading into something resembling a career crisis. Then came a personal crisis as well. His first wife and three of his four children were killed in a plane crash at Kennedy Airport in June 1975. Berlind reassessed his life. As he later told a journalist, “Everybody should get rid of his identity at one point. The worst is just going along.” He had had enough of banking, he decided, and wanted to spend more time with his son. He quietly, finally, walked away. He became an outside director of the firm (he still is an outside director of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.). And he returned to his first love, music and theater.

Berlind’s first venture on Broadway was a share in Rex, a musical about Henry VIII with a score by Richard Rodgers and lyrics by Sheldon Harnick. It was a resounding flop. Undeterred, Berlind set about learning the basics of producing, just as he had once tackled the art of Wall Street trading. “After a couple of years I had three or four failed shows,” says Berlind. “I didn’t have a success until Amadeus in 1980, but I got to understand the business.”

Berlind’s life in the theater is a balancing act between passion, on the one side, and pragmatism, on the other. “I have to love the project or the play,” he says. “But I always create a model that shows a profit at the end of the day. I ask myself: How do you get to the bottom line here? What do you need to do to recoup the investment?”

As Berlind says, being a Broadway producer is like running a small business. (Because of the costs involved, almost all new Broadway ventures are produced by a team, he says.) He ticks down the list of details. First there’s the licensing deal to get the rights to a play. Then come contracts with the stage director, the choreographer, the designers, and the actors, who are represented by Actors’ Equity. After that come negotiations with the local musicians’ union. And then, of course, there’s the contract with theater owners to rent the space. “And if there are animals, you need an animal handler; and if there are children, you need to hire people to take care of them,” says Berlind. And that’s before the accountants, press, advertising, and marketing forces are assembled. Just as in his banking days, he is known as a great team player with “an ability to foster both creative and business collaboration,” says Rocco Landesman.

A producer’s daily life — sometimes frantic, occasionally eerily quiet — takes some getting used to. “Sometimes I have nothing on the boards,” says Berlind, “and sometimes three different things, with seven or eight more projects under discussion.” If a new show opens well, “about a week later, you’re home free.” Conversely, “If it’s in trouble, it takes a lot of time,” says Berlind, with a rueful laugh. Within the industry, the rule of thumb is that “a musical can overcome bad reviews, as can a comedy with a star,” he says. But a bad New York Times review for a serious play is deadly — something that Berlind thinks is a big problem for the theater business.

Berlind feels passionately that a love of theater should be encouraged early in life. And so, as his producing career took off, he began to think of doing something specifically for the theater program at Princeton. A former University trustee (and father of William ’95), he had already endowed the Roger S. Berlind ’52 Professorship in the Humanities, held by Joyce Carol Oates. What, Berlind wondered, might he do to make a difference for students interested in the theater?

The answer came in 1994, not long after Michael Cadden became director of the Program in Theater and Dance. Cadden had gone into New York one day to have lunch with Berlind. Over dessert, Berlind asked “what one thing he could do to get Princeton’s theater program on the map,” Cadden says. Cadden immediately suggested a new, smaller theater to supplement the big space at McCarter Theatre.

At the time, the theater program had to make do with the Matthews Acting Studio — a bare-bones “black-box” theater space with lights but no backstage or wings. “Knowing McCarter’s desire for a second stage, I thought it was a natural to go in with them,” says Cadden, with a smile. “And the fact is, there’s nothing like a building to show Princeton’s commitment to theater and dance.” Berlind loved the idea. He followed up with a meeting with undergraduates. “I asked them what they wanted most,” recalls Berlind, “and what would make the theater program better. It was clear that they needed a new theater space.” Berlind offered to pay $3.5 million, a third of the theater’s cost, proposing that McCarter and Princeton each pay for one-third.

The problem was that a new theater wasn’t on the University’s wish list of building programs in the 1990s. So Berlind spearheaded a campaign to change the University’s mind. “I gather football games were particularly useful,” says Cadden, remembering how then-president Harold Shapiro *64 “caved after Roger, who was sitting by him at football games, kept yelling, ‘How’s the theater?’” Still, it took four or five more years “after it was green-lighted” to complete the Berlind Theatre. The result, a handsome red brick extension to McCarter’s imposing exterior, with its own entrance prominently located across from the train station, has proved extremely successful. Inside is a 350-seat theater, along with several capacious rehearsal rooms. Just as Cadden predicted, not only has it enriched McCarter’s offerings by allowing different work to be produced, it has raised the visibility of Princeton’s drama and dance offerings. “What’s unusual is having students write and direct plays in an absolutely state-of-the-art theater,” says Cadden. Berlind couldn’t be happier with the students’ involvement. “Get ’em when they’re young,” he says. “That’s what’s important.”

It is a pleasant fall evening, and Berlind is relaxing on the terrace of the airy, light-filled apartment in Manhattan he shares with his wife of 26 years, the former Brook Wheeler (“the toughest critic I know,” he says). Here, surrounded by books and a formidable collection of modern art, Berlind seems both expansive and optimistic. There have been times over the years, he acknowledges, when he was deeply worried about the future of theater in the United States. “About 10 years ago I thought the world was coming to an end,” he says. “The economy was an important element in that. But right now I’m very positive. There’s been a terrific period of growth that has benefited theater attendance. Production and operating costs have gone up, but so have ticket prices. And it hasn’t inhibited traffic; more people are going to the theater, and there’s a real hunger for serious work off- and off-off-Broadway.”

Berlind also sees lots of opportunity for new producers. “Even if a play doesn’t work on Broadway, it can do well in an afterlife,” he says. “Passion, for example” — the Sondheim musical — “was not successful on Broadway. But it has been produced in half a dozen different locations, both in an opera house and in theaters. And Hollywood is looking for material to develop. Writers are thrilled with this second life in stock and amateur productions and possible movies.”

Ask Berlind about what lies next for him, and he leans forward and gestures animatedly as he speaks. He’s going to be involved with Faith Healer, a revival of the Brian Friel play, with Ralph Fiennes as the lead. There’s an upcoming Virginia Woolf production in London. And then there’s Curtains, a new musical that Berlind is producing jointly with the Center Theatre in Los Angeles that will open on Broadway by the spring of 2007. “It’s a backstage murder-mystery musical comedy that makes fun of the genre,” he says. “It’s about a troupe doing an out-of-town tryout in Boston. The show they’re putting on is terrible. The first murder is at the curtain call on opening night, and the dead bodies start multiplying. And there’s the funniest detective ever. From start to finish, the whole thing is hysterical.”

A murder-mystery musical comedy spoof, built upon a terrible play-within-a-play?

It may sound tricky to pull off, but don’t bet against Berlind just

yet. After all, the last Broadway show answering to that description —

a musical comedy send-up, based on a terrible show-within-a-show —

was none other than The Producers. And the rest, as they say,

is box-office history. ![]()

Annalyn Swan ’73 is the former senior arts editor of Newsweek. She is the author, with Mark Stevens ’73, of the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography de Kooning: An American Master.