|

February 15, 2006: Notebook

Arts 101: Lewis ’55 makes a record gift

Views of another time and place

At Princeton, Clinton takes hard line on Iran’s nuclear ambitions

What we are missing: Listings from the course guide

Breaking ground—astrophysics

Searching for far-flung planets

President Tilghman and Peter B. Lewis ’55 after Tilghman announced Lewis’ $101 million gift to fund Princeton’s arts initiative. (Denise Applewhite/Office of Communications) |

Arts 101: Lewis ’55 makes a record gift

Peter B. Lewis ’55 has donated $101 million to fund a broad arts initiative at Princeton that is expected to include additional faculty and courses, an administrative center for the arts, an artists-in-residence program, and new studio, performance, and exhibition spaces, the University announced Jan. 20. Lewis’ gift is the largest in University history, surpassing the $100 million given by Gordon Y.S. Wu ’58 in 1995.

Lewis, a University trustee and the chairman of the Progressive Corp., an Ohio-based auto insurance company, has given a total of $220 million for projects at Princeton that include the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics and the Frank Gehry-designed science library currently under construction. For the last 30 years, Lewis has been a noted patron

of the arts, but his appreciation of art began after college. “Had there been more of an arts presence on campus, I might have learned the importance of it and the joy of it a lot earlier in life than I did,” he said. “Having a vibrant arts presence enhances any institution.”

President Tilghman called the gift the start of a “new era” for the arts at Princeton that will build on existing programs in creative writing, theater and dance, musical performance, and visual arts. “These programs increasingly attract excellent students,” Tilghman said in a prepared statement, “but Peter’s gift will give us an opportunity to establish Princeton more fully as a national and international destination for the very best students with talents and interests in the arts.”

Tilghman’s effort to expand the arts gathered momentum in the last year. She convened a committee of 13 faculty members and administrators last spring, asking for suggestions of areas where Princeton could invest in the arts. The committee’s charge was to think big, which made some wonder if there was a “gift in the wings,” according to committee member Michael Cadden, director of the Program in Theater and Dance. “But in my wildest dreams, I did not think it would be anywhere near the size of Mr. Lewis’ gift,” Cadden added.

The committee presented recommendations to Tilghman in the summer, and in November, she opened a campuswide discussion of the arts at a meeting of the Council of the Prince-ton University Community. Ten weeks later, Tilghman announced Lewis’ gift and outlined the new arts initiative.

Arts committee chairman Stanley Allen *88, the dean of the School of Architecture, said that the initiative reflects the committee’s recommendations, which aimed to capitalize on Princeton’s strengths, such as the emphasis on undergraduate education and an interdisciplinary culture. The initiative also will enhance the University’s role as a patron of the arts, Allen said, by commissioning new art, supporting artists, and providing arts venues accessible to the community.

In a report presented to the trustees shortly before the announcement of Lewis’ gift, Tilghman outlined a plan to make the arts available to all undergraduates. “Just as our distribution requirements reflect the belief that competence in scientific and mathematical reasoning should be required of a Princeton graduate,” she wrote, “so too should our curricular choices affirm that exposure to the creative arts prepares students to become more effective citizens and future patrons of the arts in their communities.”

To accommodate growing demand, Tilghman called for more courses in all arts programs and additional faculty, in both tenure-track and short-term appointments. To manage the expanding offerings, she recommended creating a center for the creative and performing arts that, much like the Council for the Humanities, would coordinate the academic programs and act as an “administrative umbrella.” The center also would oversee a proposed fellowship program to bring six innovative, early-career artists in varied disciplines to campus each year, for two-year terms, to teach undergraduates and create art while at Princeton.

Tilghman proposed new space in the context of an arts “neighborhood,” probably either in a new building on Alexander Street, south of the McCarter and Berlind theaters, or in renovated spaces at Green and Frick halls, adjacent to 185 Nassau Street, the current home of the visual arts, creative writing, and theater and dance programs.

Tilghman did not recommend creating departments with academic majors

in the creative and performing arts, but her report left that possibility

open for the future. The full report is available online at http://www.princeton.edu/pr/

reports/arts. ![]()

By B.T.

(PUAM) |

Views of another time and place

“Portrait of Tsar Alexander III Holding a Report,” left,

a 1900 painting by Valentin Serov, is one of more than 80 works from Russia

that will be on display Feb. 25 through June 11 at the University Art

Museum. The exhibition, Mir Iskusstva [World of Art]: Russia’s Age

of Elegance, has strong alumni connections. It was organized and presented

by the Maryland-based Foundation for International Arts & Education,

headed by Greg Guroff ’62 *70, and University trustee Tony Evnin

’62 is a major benefactor. Works from the World of Art movement,

which thrived in Russia at the turn of the 20th century, were long suppressed

after socialist realism became the governing Soviet philosophy. A series

of special University events will be tied to the exhibition; check the

museum’s Web site (www.princetonartmuseum.org) for details. ![]()

Sen. Hillary Clinton spoke about Iran and Israel at Princeton last month. (Frank Wojciechowski) |

At Princeton, Clinton takes hard line on Iran’s nuclear ambitions

Visiting Princeton last month to celebrate a new professorship devoted to Middle East studies, Sen. Hillary Clinton pledged firm support for Israel and promoted a policy of optimism “with a strong strain of realism” in the region. Clinton also took a hard line on Iran’s efforts to enrich uranium, saying that the United States and the United Nations “cannot take any option off the table” in efforts to prevent Iran from acquiring nuclear weapons.

Clinton, D-N.Y., was invited to campus by Daniel Abraham, a businessman and philanthropist who endowed the new chair, which is held by Daniel Kurtzer. Kurtzer was the U.S. ambassador to Israel during President George W. Bush’s first term and the ambassador to Egypt during President Clinton’s second term. (An interview with Kurtzer is on page 64, click here to read.)

In discussing America’s Middle East policy at Princeton Jan. 18, Sen. Clinton said the United States should show humility and accountability in its exercise of power, and base decisions on evidence rather than ideology. Speaking a week before the Palestinian general elections, she urged Palestinians to curb terrorism and govern peacefully, saying they had “no more excuses.” Clinton also criticized the Bush administration’s handling of Iran’s nuclear ambitions. “I believe that we lost critical time in dealing with Iran because the White House chose to downplay the threat and to outsource the negotiations,” she said. “I don’t believe you face threats like Iran or North Korea by outsourcing it to others and standing on the sidelines.”

Students, staff, and faculty picked up all available tickets for the free event on the day it was announced, and Clinton drew a warm and enthusiastic response from the audience. She did not take questions.

At the end of her 45-minute address, Clinton thanked students for taking

a break from studying for first-semester exams. “I don’t mind

at all being an excuse for procrastination,” she said. “But

I can’t keep going too much longer without fear of being blamed

for whatever may befall you if you do not go back and study.” ![]()

By B.T.

(Office of Communications) |

Dean Maria Klawe will leave Princeton’s School of Engineering and Applied Science to become president of Harvey Mudd College in Claremont, Calif., effective July 1. Harvey Mudd College focuses on engineering, science, and mathematics.

Klawe, who became dean in January 2003, led the year-long development of SEAS’ strategic plan, resulting in the creation of new classes, an enhanced technical education, and a focus on the interaction between technology and social and economic forces. In a letter to engineering faculty, staff, and students, Klawe said she “will continue to work hard for Princeton over the next five and a half months and prepare for a transition in leadership that will build on our momentum.”

A computer scientist, Klawe had high-level positions in both academia

and industry before coming to Princeton. ![]()

What we are missing: Listings from the course guide

It’s the beginning of a new semester — the time when we feel special envy toward students who are able to put the spring course catalog to use, exploring new passions and delving into old ones, even as they complain about dragging themselves to classes that begin before noon. The rest of us are left to dream — and, perhaps, buy a few books on the reading lists. This spring the hundreds of courses being offered include 106 new ones, from “Thomas Jefferson’s America” to “Documentary Filmmaking” to “Catholic Theology after the Second Vatican Council.” Here’s a glimpse into a handful of the new offerings, with course-catalog descriptions and comments from the professors.

AMS

309: The Christian Right and the Open Society

AMS

309: The Christian Right and the Open Society

Professor: Christopher L. Hedges

Description/objectives: The course will examine the ideology and rising influence of the Christian Right. It will allow students to combine the skills and interests of a researcher and academic with those of a journalist. Students will study the worldview of the Christian Right through readings, viewing of Christian broadcasts, and reporting. They will closely examine the critique the Christian Right makes of the “secular humanist” society, as well as the splits and internal schisms that define the movement.

Students will be expected to attend meetings of radical groups such as Operation Rescue, church services, and prayer groups. Students will interview followers to find out what participation in the movement means for them as individuals and how the movement defines and shapes their lives.

Sample reading list: Robert O. Paxton, The Anatomy of Fascism; Karl R. Popper, The Open Society and Its Enemies (Plato); Hannah Arendt, The Origins of Totalitarianism; Mel White, Stranger at the Gate: To Be Gay and Christian in America; Rousas John Rushdoony, The Institutes of Biblical Law; Tim Lahaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, Glorious Appearing: The End of Days

Hedges, a New York Times reporter who is known for his book about war and nationalism, War is a Force That Gives Us Meaning, is writing a book on the religious right, the subject of this American Studies seminar. Hedges, the son of a Presbyterian minister, “grew up in the church,” he says, and later went to divinity school at Harvard. Today he is concerned about the religious right — and liberal theologians — who “turn political discourse into a form of Christian hermeneutics.” Hedges explains: “I wanted to let students take a look at the language and ideas behind this movement sweeping across the country, to let them explore what it means for those of us who care about an open, pluralistic, and tolerant America.”

Hedges says he selected the books so that students could study “the philosophical and linguistic underpinnings of totalitarian movements. I want them to grasp how these movements operate and why they do or do not succeed. Writers such as Karl Popper and Hannah Arendt have done masterful jobs of exposing the core of these despotic movements, and they eloquently defend the virtues of the open society.”

ENG

403: Forms of Literature: Global English

ENG

403: Forms of Literature: Global English

Professor: Simon E. Gikandi

Description/objectives: English is spoken by over 1.5 billion people in the world and has produced great literature in all corners of the globe. How did this language, once spoken by a small number of Anglo-Saxon peasants, become the language of globalization? How has the emergence of global English affected the form of modern literature? In this course we will explore the stories of global English, focusing on works that have been most influential in the globalization of the language. We will explore how certain “master texts” of English have traveled worldwide, exerting influence on and in turn being influenced by the cultures they have encountered.

Sample reading list: Charles Dickens, Oliver Twist; V. S. Naipaul, Miguel Street; Michael Ondaatje, Anil’s Ghost; Nick Hornby, High Fidelity; Barbara Kingsolver, The Poisonwood Bible; Zadie Smith, White Teeth

A native of Kenya, Gikandi has long been interested in how the English language and English literature have influenced African languages and cultures, and vice versa. In this course, students will explore the effects of — and influences on — English in cultures around the world. “I have to emphasize that English is not simply a language but also a cultural formation with all sets of assumptions and ideas,” Gikandi says. “My concern is how this formation is changed when writers and subjects are located outside England.”

Gikandi explains that he selected books “that did one of two things: (1) expressed an overt sense of English as a global language, one that is constantly transformed as it is transported to different geographical spaces; or (2) were rewriting, in one form or another, the canonical texts of Englishness.” As an example, he cites Chinua Achebe’s novel, Things Fall Apart, which is set in a traditional, Nigerian community. “Its title comes from a poem by Yeats (‘The Second Coming’) and its language draws heavily from the King James version of the Bible; but the novel has in turn influenced the works of contemporary writers such as the American novelist Barbara Kingsolver,” he says.

GEO

298: Controversies in Science

GEO

298: Controversies in Science

Professor: Samuel G. Philander

Description/objectives: Is the Earth flat or round? Is it a few thousand or a few billion years old? Do continents drift? Were there recurrent Ice Ages in the distant past? This course explores the heated debates these questions generated before scientists agreed on the answers. In light of this history, the course then examines current debates about intelligent design and global warming.

Sample reading list: D.J. Boorstin, The Discoverers; Bill Bryson, A Short History of Nearly Everything; E.G.R. Taylor, Ideas on the Shape, Size and Movements of the Earth; G. Brent Dalrymple, The Age of the Earth; N. Oreskes, Plate Tectonics; T. Crowley and G. North, Paleoclimatology

Debates over science are common in today’s culture; intelligent design is getting a hearing in school board meeting rooms and courtrooms, and global warming is the stuff of novels and movies (Philander notes that Hollywood’s The Day After Tomorrow showed abrupt climate change plunging the planet into chaos, while Michael Crichton’s 2004 thriller State of Fear, published a few months later, expressed skepticism about global warming). While intelligent design and global warming were the impetus for Philander’s course, he notes that such debates are not new. “We have had many scientific controversies in the past. How did we resolve them?” he asks. “Can [historical] experience help us with current disputes? Those are the questions the course will address.” Philander points out that intelligent design is hardly a new idea; Thomas Aquinas mentioned it centuries ago.

POL

380: Human Rights

POL

380: Human Rights

Professor: Gary J. Bass

Description/objectives: A study of the politics and history of human rights. What are human rights? How can dictatorships be resisted from the inside and the outside? Can we prevent genocide? Is it morally acceptable and politically wise to launch humanitarian military interventions to prevent the slaughter of foreign civilians? What are the laws of war, and how can we punish the war criminals who violate them? Cases include the Ottoman Empire, Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union, Bosnia, and Rwanda.

Sample reading list: Hannah Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem; Michael Ignatieff, Human Rights as Politics and Idolatry; Samantha Power, A Problem from Hell; David Rohde, Endgame; Michael Walzer, Just and Unjust Wars; David S. Wyman, The Abandonment of the Jews

Bass, a former reporter at The Economist magazine, has spent his years in academia researching human rights and international justice. “This is a class very close to my research interests,” Bass notes; the class includes segments on the subject of his last book (war crimes, in Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes Tribunals) and on the subject of his next book, humanitarian military intervention. By mid-December, about 90 students had signed up.

“The course is primarily about what human rights are, how dictatorships can be undermined by human rights, whether and how to launch humanitarian military interventions to stop mass murder in foreign countries, whether and how to prosecute war criminals, and about how human rights matter in American foreign policy after Sept. 11,” Bass explains. Students will consider the cases of Nazi Germany, Bosnia, Rwanda, communism in Eastern Europe, and the ongoing killings in the Darfur region of Sudan. Iraq is also part of the story, and Bass and his students will assess human rights arguments for toppling Saddam Hussein and U.S. abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. “Since it’s a course on human rights, I don’t want it to just be about the places that Americans already pay attention to, but also about places that get ignored — like Darfur,” he says.

![]() JDS

342/GER 342/COM 342: The Voices of Yiddish: Literature, Film, Music

JDS

342/GER 342/COM 342: The Voices of Yiddish: Literature, Film, Music

Professor: Esther H. Schor

Description/objectives: Wise and foolish, strident and tender, pious and skeptical — these are the many voices of Yiddish, in literature, film, and music. The course moves from classics of Yiddish writing — S.Y. Abramovitsh, Sholem Aleichem, and I.L. Peretz — to Yiddish modernism in urban settings, from Vilnius and Warsaw to New York. All texts will be read in translation. We will explore Yiddish responses to the Holocaust by Chaim Grade and I.B. Singer and transformations of Yiddish traditions in the hands of women writers, dramatists, and filmmakers. We will close by considering the current international Klezmer revival and its implications for Yiddish continuity.

Sample reading list: I.L. Peretz, The I.L. Peretz Reader; Sholem Aleichem, Tevye the Dairyman; S.Y. Abramovitsh, Tales of Mendele the Book Peddler; Chaim Grade, My Mother’s Sabbath Days; I.B. Singer, Satan in Goray; Frieda Forman, et al., Found Treasures: Stories by Yiddish Women Writers

All around her, Schor says, she sees a blossoming of interest in Yiddish, the language of Eastern European Jews. New translations of Yiddish works are being published; efforts are being made to preserve Yiddish books. Still, scholars believe Yiddish is at a crucial juncture.

“It’s not melodramatic to say that the fate of Yiddish is hanging in the balance,” says Schor, a professor of English who teaches in the Program in Judaic Studies. “I want to persuade students that they have an important choice to make: whether to grant Yiddish the dignity of a vernacular in which Europe’s Jews spoke, worked, argued, loved, and wrote, or to caricature it as a language old people speak in Jewish jokes. Don’t get me wrong — I love those jokes. But to let them define a rich language with a vibrant literature and a thousand years of history is untenable. I want to immerse my students in the sounds and images of Yiddish culture as well as its texts.” Though Schor has long dreamed of teaching the course, “it took a trip to Eastern Europe last spring to awaken me to just what is at stake.”

“Yiddish literature shuttles back and forth between traditional Jews and modern ones; between shtetl and city; between prose and lyric poetry; between text and film,” Schor says of her reading list. “Yiddish is, above all, a contested language; it has been the occasion for Jews to argue about their differences for 800 years. I’ve tried to find works that venture into these ferocious debates.”

PHY

116: Music and Physics

PHY

116: Music and Physics

Professor: Pierre A. Piroué

Description/objectives: This course teaches some basic physics using music. It is designed for nonscientists who love music and would like to learn more about how it is made. Unlike traditional courses in the physics of music that start with physical concepts and then move to the musical applications of those concepts, this course develops the physical concepts and musical applications together. This approach makes the course more accessible to nonscientists and better explains the interplay of music and physics.

Sample reading list: Ian Johnston, Measured Tones, The Interplay of Physics and Music; Juan G. Roederer, The Physics and Psychophysics of Music, An Introduction

When Piroué was young, he tells his students, to be cultured meant to know art, music, literature, and to have studied Latin and Greek. Science was nowhere on the list. “But nowadays,” he continues, “to be completely ignorant about science, you cannot pretend to be a cultured person. It’s impossible.” His course, first created as a freshman seminar three years ago, aims to create cultured students by teaching concepts of physics through music. In lectures and labs — with lots of music performed by students — students learn about topics such as vibrations, oscillations, wave theory, and the overtones of a bowed string. The last lab will be a student music recital.

Though the professor had planned for 16 students, 59 had signed up by

mid-December and additional lab sessions were created. “The only

requirement is to love music,” says Piroué, a physicist and

a pianist who plays “a little bit” of trumpet. “You

don’t have to love physics.” ![]()

By M.H.M.

Along with executive power and Roe v. Wade, one of the biggest discussion topics at last month’s Senate Judiciary Committee hearings on the nomination of Samuel A. Alito ’72 to the U.S. Supreme Court was Princeton — specifically, Alito’s membership in a defunct conservative group called the Concerned Alumni of Princeton (CAP). Alito had listed his membership in CAP, which was active in the 1970s and 1980s, in his 1985 application for a job in the Justice Department; senators wanted to know about his involvement and his reasons for joining.

While acknowledging that he did belong to CAP, Alito insisted that he never was an active member and said he disagreed with statements in the group’s magazine, Prospect, opposing the admission of women and minorities. He speculated that he joined because of his disagreement with a University decision to prohibit ROTC recruiters from campus.

There were some hot Princeton-related moments, including an argument between Sen. Edward Kennedy, D-Mass., and Sen. Arlen Specter, R-Pa., over Kennedy’s demand that the committee subpoena CAP documents in the papers of William Rusher ’44, a group founder. At one point, Kennedy read into the record an article from Prospect titled “In Defense of Elitism” as evidence of the group’s views; a former Prospect editor, Dinesh D’Souza, later suggested that the article had been a parody. Sen. Joseph Biden, D-Del., jokingly informed Alito that “I really didn’t like Princeton” — but the next day he appeared wearing a Princeton cap.

Even the nominee appeared to have mixed views of his alma mater. On

the first day of hearings, he contrasted the “very smart people

and very privileged people behaving irresponsibly” on campus to

the “good sense and the decency of the people” in his middle-class

New Jersey hometown. But later Alito said that since graduating, he has

been involved in the Alumni Schools Committee, which “shows my attitude

toward the general way in which the University has been run.” ![]()

By M.F.B.

(Photo by Denise Applewhite) |

“In addition to the ‘I have a dream’ speech, we must think about the lifelong legacy that [Martin Luther King Jr.] left for us and the standards of leadership that he gave to us. I think of them often, and I think of how important they are, to uplift me and to keep me going.”

Marvalene Hughes, president of Dillard University, a historically black

college in New Orleans that was severely flooded after Hurricane Katrina,

in a speech at the Martin Luther King Jr. Day celebration at Princeton

Jan. 16. Hughes credited Princeton and Brown University for aiding Dillard’s

efforts to reopen. ![]()

The dark portion of a crescent moon is visible because of “earthshine,” or reflected light. (Courtesy Chris Cook Photography)

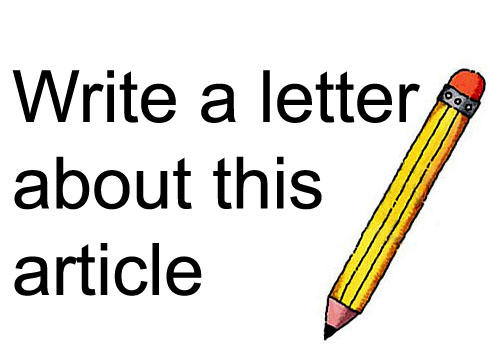

Professor Edwin Turner in western Victoria, Australia, near where he and a colleague investigated earthshine. (courtesy Edwin Turner) |

Breaking

ground—astrophysics

Searching

for far-flung planets

When a crescent moon lights up the night sky, the dark portion of the moon is often visible as well, though the sun never reaches it directly. The reason is earthshine, a concept first diagrammed by Leonardo da Vinci in the 16th century: Sunlight reflects off Earth, shines on the dark part of the moon, and reflects back to Earth. While the concept is nothing new, astrophysics professor Edwin Turner says it may prove very useful as scientists work to identify Earth-like planets outside our solar system.

In the next decade, NASA plans to launch its Terrestrial Planet Finder mission, using powerful telescopes to search nearby stars for previously undetected planets. If a planet of Earth’s size exists, it would appear as a faint point of light separate from the star. The challenge is to learn as much as possible from that point of light, including whether the planet might support life. That’s where earthshine could help, Turner says.

Other terrestrial planets, such as Mars or Venus, reflect light at a fairly uniform rate. But as Earth rotates, oceans, landmasses, vegetation, and clouds reflect varying amounts of light, creating what Turner calls a “signature” unique to Earth. By using earthshine to determine how Earth’s fluctuating light curve would appear if viewed from a distance, astronomers could compare it with the light observed from other planets and infer the presence or absence of oceans and large landmasses.

The easiest way to gather information about Earth’s reflected light is to measure the visible light on the dark portion of the moon, which Turner did most recently on a December trip to Australia. Turner and colleague Stuart Wyithe from the University of Melbourne used a mobile setup that included a somewhat pedestrian-looking telescope on a tripod, an astronomical camera powered by a car battery, and a laptop computer plugged into the cigarette lighter of their station wagon. “Not very many people came by,” Turner says, “but if you had been driving down a road in western Victoria near Mount Arapiles and seen us there, I don’t think anyone would have thought that we were doing innovative scientific research.”

With minimal cloud cover and both the sun and moon in the southern sky,

the conditions in Australia were ideal, producing what Turner calls some

of the best earthshine data he has seen. But there is still plenty of

work to be done, both in analysis and in gathering more information. Turner

and others studying earthshine are willing to endure the tedium of data

collection in exchange for the chance to help answer the ancient question

of whether there are other worlds like our own. Science fiction has envisioned

a plethora of far-flung planets with interesting life forms, Turner says,

“but the scientific reality is that we just don’t know. That

could be correct, or there could be virtually no other places like our

solar system.” ![]()

By B.T.

(Office of Communications) |

ALUMNI DAY on Saturday, Feb. 25, will feature lectures, family programs, and the Alumni Association’s annual luncheon and awards ceremony. Madison Medalist Arthur D. Levinson *77 (above, left), chairman and CEO of Genentech Inc., will speak at 9:15 a.m., and Woodrow Wilson Award recipient George E. Rupp ’64 (above, right), president of the International Rescue Committee, will speak at 10:30 a.m., both in Richardson Auditorium. There also will be talks on Woodrow Wilson 1879, Sino-American relations, the wireless revolution, and intellectual property issues; a tour of the Plasma Physics Lab; and performances by the Juggling Club. Register online at https://alumni.princeton.edu/events/adregform.html.

“THIS IS PRINCETON,” an annual student-run talent show, will be held Friday, Feb. 24, at 8 p.m. in Richardson Auditorium. Undergraduates, graduate students, faculty, staff, and alumni will offer a variety of performances, including music, comedy, photography, and theater pieces. The program had not been finalized as of the end of January, but in past years, the evening has featured all sorts of student and alumni musical performances and faculty luminaries such as writer John McPhee ’53 and poet Paul Muldoon reading from their work. Tickets are $6 for students and $10 for others. The proceeds benefit local arts programs.

The Richardson Chamber Players, a group made up largely of professional musicians who teach at the University, will perform Aaron Copland’s “APPALACHIAN SPRING” Sunday, Feb. 19, at 3 p.m. in Richardson Auditorium. Also on the program are works by George Anthiel, Arthur Farwell, and Charles Griffes. Tickets can be ordered through the Richardson ticket office at 609-258-5000.

“GOD AND WAR” is the theme of a series

of three Stafford Little lectures to be given by Mark Juergensmeyer on

Feb. 21, 22, and 23 at 8 p.m. in McCosh 50. Juergensmeyer is director

of global and international studies at the University of California, Santa

Barbara and is the author of “Terror in the Mind of God: The Global

Rise of Religious Violence,” a book based on interviews with violent

religious activists around the world. ![]()

In January, University trustees approved a $1 billion OPERATING BUDGET for 2006–07 that includes a 4.9 percent increase in tuition, room, and board to $42,200 per year, a corresponding in-crease in financial aid, and $500,000 for new allocations. Additional graduate-student teaching hours will account for nearly a quarter of the budget additions. Provost Christopher Eisgruber ’83, the chairman of the Priorities Committee, said that “teaching-intensive” courses like the freshman introductory program for engineering, math, and physics and the two-year course in integrative genomics have increased demand for teaching assistants.

The budget also increases funding for library acquisitions and admissions outreach to minority and low-income students. Staff additions will include a full-time director of disability services, a strength and conditioning coach in athletics, and additional time for the staff psychiatrist at McCosh Health Center. The Priorities Committee report is available online at www. princeton.edu/~provost/priorities.html.

German media outlets reported in January that former foreign minister JOSCHKA FISCHER has been invited to join Princeton’s faculty. Princeton spokeswoman Cass Cliatt ’96 would not comment, saying “personnel issues are not made public.”

A popular politician who left office last November, Fischer weathered a crisis in 2001 over his past as a militant left-wing activist involved in violent street battles with police in the 1970s.

A cancer-fighting compound developed in a Princeton chemistry lab has generated a breakthrough drug and a corresponding spike in the University’s PATENT AND LICENSING INCOME. According to the University Research Board’s annual report, royalty revenue increased more than tenfold, from $982,000 in 2003–04 to almost $10.6 million in 2004–05, largely due to the February 2004 FDA approval of Alimta, an Eli Lilly Co. cancer drug that uses a compound generated by emeritus professor Ted Taylor more than 15 years ago.

The drug, now approved in more than 30 countries, has prolonged life for patients with second-line lung cancer and mesothelioma, a cancer usually linked to asbestos exposure.

“Blue Gene,” a SUPERCOMPUTER that the University says is one of the 100 most powerful in the world, has arrived on Prospect Avenue. About the size of a large refrigerator, the computer consists of 2,048 processors. Blue Gene, named for its earlier work in gene mapping, was purchased from IBM.

A $475,000 grant from the Goldman Sachs Foundation will support the

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PREPARATORY PROGRAM and fund a national

conference at Princeton this year for institutions that offer similar

programs designed to help low-income, high-achieving high school students

prepare for selective universities. The grant will help pay for two years

of the program’s activities. ![]()