|

November 22, 2006: Notebook

Strong year pushes endowment to $13 billion

BREAKING GROUND—electrical

engineering

Hiding secrets, under the noise

Grade deflation concerns linger

Recalling Prospect Club’s ‘great social experiment’

Strong year pushes endowment to $13 billion

The University’s endowment grew to $13 billion in the 2006 fiscal year with a 19.5 percent return on investments, according to the Prince-ton University Investment Company (Princo). The rate of return, which was reported to Princo’s board of directors Oct. 25, was the University’s highest since 2000, exceeding the 16.8 percent and 17.0 percent returns of the last two years. The change in the endowment’s value is a function of spending, gifts, and investment performance.

Princo president Andrew Golden downplayed last year’s figure, highlighting instead Princo’s success in the last decade. Nationally, the median endowment grew 9.6 percent per year in the last 10 years, according to Cambridge Associates, which surveys 122 college and university endowments, while Princeton’s endowment compounded at a rate of 15.6 percent per year. Had the endowment grown by the median rate since 1996, its market value would be about $8 billion today.

Princo’s emerging-markets portfolio led last year’s charge with a 41 percent return, paced by the growth of investments in Brazil and Russia. Private equities and real assets, which include real estate, energy, and natural-resource investments, grew by more than 20 percent. And in a period when the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index rose 6.6 percent, each of Princo’s equity categories saw double-digit returns. “We had great returns, and more importantly, we had very successful activity, which should position us well for future success, at least on a relative basis,” Golden said.

According to Golden, Princo is just beginning to see the fruits of its effort to improve the quality and quantity of relationships with money managers abroad. The University has been investing internationally for decades, but many of those investments were made through U.S.-based managers. “We wanted to get money into the hands of local experts,” Golden said.

Golden, managing directors Jon Erickson and Dan Feder, and their colleagues have logged more than a half-million air miles to help Princo expand its investments abroad. Two years ago, a dozen managers based outside the U.S. invested $500 million of endowment funds. Today, Princo works with 33 managers abroad who invest $3 billion in international equities, private equities, and real assets.

The international expansion is one example of the advantages that large university endowments have over smaller ones. Finding good managers is labor-intensive, Golden said, and large endowments can afford the labor. “It’s more cost-effective to amortize a trip to Shanghai over a $13-billion base than it would be over a $500-million base,” he said.

In 2005, endowments that exceeded $1 billion reported an average return of 13.8 percent, according to the Chronicle of Higher Education. The same year, endowments in the $500 million to $1 billion range earned an 11.3 percent return.

Princeton’s endowment is the fourth largest among private universities, be-hind Harvard, Yale, and Stanford, and its 2006 return ranked second among those four. Yale led the way with a 22.9 percent return; Stanford had a 19.4 percent return, and Harvard’s endowment grew 16.7 percent.

Among institutions that grant undergraduate degrees, Princeton ranks

second nationally in endowment per student, behind the Franklin W. Olin

College of Engineering in Massachusetts. Endowment income is projected

to fund about 37 percent of the University’s $1 billion operating

budget in 2006-07, according to the 2006 Priorities Committee report.

![]()

By B.T.

(Ron Barrett) |

On YouTube, the popular video-sharing Web site, viewers can find a range of Princeton-related flicks, from a breakdancing competition at Dillon Gym to a colorful chemistry experiment performed to the tune of “The Orange and the Black.” But in terms of viewership, one Princeton video stands above all others: “The Watergun Revenge.”

The video, which has been screened nearly 90,000 times since June 29, shows a 2001 prank in which Tyson Knight ’03, Brian Weiss ’03, and a few friends in black suits and dark glasses calmly enter a lecture by Professor James McPherson in McCosh 50, soak Ryan Salvatore ’02 with heavy-duty water guns, and file out the front door. Salvatore, clearly stunned, stands and flips through his notebook, searching for a dry page, as McPherson inquires about what the student did to deserve the dousing.

The story started on an Outdoor Action trip that Salvatore and Knight had led that fall. The two made a bet — both are mum on the details — and when Salvatore lost, he paid up with 1,000 pennies, tossed on the floor of Knight’s dorm room. Knight vowed payback, memorialized on film.

“The Watergun Revenge” was filmed with three cameras — one in the balcony, one at desk level, and one following the shooters — and edited by Nick Confolone ’03, who initially screened it on the campus public-access channel, TigerVision, in 2002. Five years after the prank, Knight is amazed by the video’s YouTube popularity. “It hit some sort of tipping point that had nothing to do with me,” he said.

The water-gun attack, on the other hand, had everything to do with Knight and Weiss, his co-conspirator. They planned meticulously, diagramming the operation, synchronizing their watches, and stashing a change of clothes in the McCosh basement so they could slip away unnoticed.

Even McPherson seemed impressed. “Let me tell you, that’s

better than some of the shenanigans that they’ve pulled on me,”

the professor tells his class in the video, alluding to streakers on campus.

“People are getting more civilized.” ![]()

By B.T.

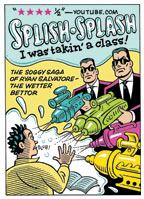

Evgenii Narimanov’s method for sending secret messages uses public fiber-optic networks. (Frank Wojciechowski) |

BREAKING

GROUND—electrical engineering

Hiding

secrets, under the noise

In a fiber-optic network, a certain amount of background noise is inevitable, a by-product of the amplifying devices that send light waves over long distances. Some may see that as a nuisance, but according to two Princeton researchers, the noise provides an opportunity for a new form of stealth communications.

Evgenii Narimanov, an assistant professor of electrical engineering, and graduate student Bernard Wu have developed a method to send highly secure, secret messages over public fiber-optic networks, such as those used for Internet service, by hiding the messages in low-power transmissions beneath the noise that occurs normally on the network. The transmissions do not affect the network’s performance and are not detectable when the network is in use.

Electrical engineering professor Paul Prucnal and members of his lab are turning Narimanov’s theory into a working system using test networks and existing cryptographic encoders and decoders. “We had this idea, we showed that it worked, and immediately we had a collaboration where the system is being built,” Narimanov says. “This thing would not fly if I didn’t have Professor Prucnal’s lab here. You need to have people from different areas and different expertise in the same place.”

Narimanov’s system combines cryptography (encoding a sensitive message) and steganography (concealing the message, in this case on a public network) so that outsiders do not even realize that the communication exists. “If you have a secure network, your opponents will always look at that and will try to break it,” Narimanov says. “It’s like a big red flag.” Public networks, on the other hand, provide several security benefits. When a public network is in use — and most are in constant use — eavesdroppers have no way of finding the secret message. Shutting down every public network to search for a message is impractical, if not impossible. And even if one did discover the encoded message, reading its contents would require a complicated correlation analysis.

The most obvious applications of Narimanov’s work are in areas such as national security or financial services, where highly sensitive information is transmitted across long distances. Narimanov has presented his work to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), but he adds that there are more immediate commercial applications within smaller networks. Narimanov’s system would allow several levels of security on a single network. For instance, on an airliner, low-security information, like in-flight movies, and more secure information, such as flight plans, could be transmitted on the same set of optic fibers.

Narimanov, who came to Princeton five years ago from Bell Laboratories,

says the first reaction of colleagues to his theory “was that it’s

impossible.” But, he adds: “People are smart, so they [soon]

realized that it’s not only possible, it doesn’t require anything

beyond the existing hardware. After that, people were quite complimentary.”

![]()

By B.T.

(Laura Sillers ’07/the Daily Princetonian) |

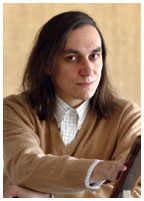

Grade deflation concerns linger

Two years after the University changed its current grading policy, recent reports on the effects of grade deflation have reignited the debate over the controversial new standards.

In late September, a study by the Faculty Committee on Grading found “no evidence of detrimental effects from the new grading policy” on students’ applications to jobs or graduate school. But opponents of the policy continue to worry about grade deflation’s effect on academic life at the University. According to a USG survey conducted last year and released in October, nearly 70 percent of students view the grading policy as a “negative ... addition to Princeton.” The survey also suggests students have become less willing to work collaboratively.

Undergraduate Student Government president Alex Lenahan ’07, perhaps grade deflation’s most high-profile critic, seized on the survey as evidence of the policy’s flaws. In a series of e-mails, he has urged students to approach professors with their concerns about the policy.

“[T]he grade deflation policy in its current form is detrimental to students at Princeton, professors at Princeton, and Princeton as a whole,” Lenahan said in one of his many e-mails.

Some faculty members have been sympathetic to the students’ complaints.

“Grade inflation feels like a victimless crime,” said assistant professor of history Michael Gordin, a member of the Faculty Committee on Grading. “Everyone is resistant [to lowering grades], even though everybody agrees in principle that something has to be done.”

But Dean of the College Nancy Malkiel, who spearheaded efforts to implement the grading policy, said that professors are “making headway toward ... grading more rigorously and responsibly across the divisions and departments.”

Controversy over the University’s grading standards started in April 2004, when Malkiel announced a proposal to curb grade inflation. The proposal — adopted by the faculty later that month — sets an “expectation” that “A’s shall account for less than 35 percent” of course grades and “less than 55 percent of the grades given in junior and senior independent work.”

Not all students reject the new grading policy, and many said they respect the goal of grade deflation, even if they found fault with its implementation.

“Princeton holding its students to a higher standard is an admirable move,” USG academics chair Caitlin Sullivan ’07 said.

But Sullivan expressed concern about respondents to the USG survey who reported being told by some professors that grade deflation was the sole rationale for the marks they awarded.

“Students should never be denied the grade that they have achieved,”

she said. ![]()

By Christian Burset ’07

A young girl covers her ears as Fred Minus, portraying a Continental

Army soldier, fires his musket Oct. 28 during Revolutionary Princeton

Day. Despite a rainy morning, more than 500 people took part in campus

activities that provided a glimpse of colonial life as part of the observance

of the 250th anniversary of the University’s move to Princeton.

![]()

(Photo by Beverly Schaefer)

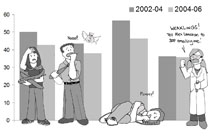

Edward A. Woolley ’51, author of a new book on the Prospect Cooperative Club. (Michael J. Maloney/Black Star) |

Recalling Prospect Club’s ‘great social experiment’

The opening of Whitman College and the inauguration of Princeton’s four-year residential colleges next fall will take place exactly one century after former University president Woodrow Wilson 1879 first presented his idea for a quadrangle plan that would “ensure vital intellectual and academic contacts, the comradeships of a common life with common ends.”

From 1941 to 1959, members of the Princeton Prospect Cooperative Club attempted a similar experiment on a smaller scale, creating a democratic and cooperative eating club. Former club president Edward A. Woolley ’51 recently self-published a history called Princeton Prospect Cooperative Club: A Great Social Experiment. Woolley spoke with PAW contributor Hilary Parker ’01 about the club, which ironically met its demise in the creation of Wilson Lodge — a precursor of the new residential-college system.

What distinguished Prospect Club from the other eating clubs on the Street?

There were four principles that were very important: democracy, egalitarianism, the co-op method, and self-reliance. Also, the faculty fellow program, which set aside Wednesday nights for faculty participation and discussion at meals, and the attitude toward minorities. It was just a total reversal of attitudes [found elsewhere at the University]. ... When I joined I recognized it as an “anti-club club” — we didn’t care what a person’s social background was. We all waited on tables or washed dishes.

How did the “Dirty Bicker” of 1958, when 23 sophomores — including 13 Jewish students — were not offered eating club bids, affect Prospect Club?

I think [the Dirty Bicker] forced the University to face the fact that it was getting more Jews and public high school graduates. They could not be treated like cattle. It took place after President Dodds [*14] made the commitment to establish Wilson Lodge, but it made it pretty obvious that some solution to the clubs’ selectivity was needed. The “non-clubmen” did not all want to go into Prospect; nor would that have been good for the University.

You explain in the book that the opening of Wilson Lodge as a nonselective venue for undergraduates ultimately led to Prospect’s closing. How did the club’s alumni react?

People really felt that it was very sad that in establishing Wilson Lodge as an alternative, [the University] also destroyed Prospect Club. ... Prospect had come to be seen [by sophomores] as part of the much-derided and contemptible club system, labeled the lowest in prestige of that system. The cooperative system was seen in terms of work required, rather than the self-reliance it engendered.

How do you see the upcoming changes to the residential-college system? How should the clubs respond?

I’m looking forward to the four-year colleges; they are very similar in their outlook to Prospect Club. In the four-year colleges I rather imagine there will be little or no socially exclusivist attitudes. I think [the clubs] ought to try to participate in the changes. My impression is that there’s still a sense of antagonism between the club system, be it sign-in or selective, and University goals, and the clubs really should be part of the University. They should have similar goals.

Did writing the book bring back memories?

While the food was considered quite good, the devil was in the details.

The efforts to legislate menus by club officers were pretty hilarious.

On May 10, 1950, a motion “to permanently institute two vegetables”

was passed by a narrow margin, 28–23. We did everything democratically.

![]()

(Photo by Frank Wojciechowski) |

“Early in a person’s career, if he fails as a leader, it is because he didn’t have the skills to get the task done. In the middle of their careers, the leaders I have seen fail, failed because they were too interested in themselves. Later in a career, it is because of two things: hubris and a lack of people skills.”

Norman Augustine ’57 *59, former chairman and chief executive

of Lockheed Martin, speaking Oct. 19 in the Friend Center. He delivered

the inaugural speech in a new lecture series, “Leadership in a Technological

World,” sponsored by the Center for Innovation in Engineering Education.

![]()

Professor Cornel West *80 inaugurated the University’s Toni Morrison Lectures with a pair of talks on Oct. 20 and 21 on “The Gifts of Black Folk in the Age of Terrorism” that drew capacity crowds to McCosh 50.

West, the Class of 1943 University Professor of Religion, explored forms of resilience that people of African descent in the United States forged in times of brutality and oppression. Such attributes have taken on renewed importance for courageous living in the post-Sept. 11 age, he said.

President Tilghman said she hopes the annual lecture series will become “one of the most important vehicles for scholars and intellectuals to reflect on race in America.” Morrison, a professor emerita and recipient of the Nobel Prize for literature, attended the event. The lectures will be published by Princeton University Press.

History has given African-Americans unhappy intimacy with questions that seem new to many Americans, West said. “When your 4-year-old child asks you, ‘Why am I hated so?’ that is a serious question,” he said. “You have to know how to respond to that without embittering him.”

Princeton can help to sustain the art of debate, freeing citizens from

the hate speech that can arise in frightening times, West said. He quoted

the mother of Emmett Till, a black teenager who was beaten to death in

Mississippi in 1955: “I don’t have a minute to hate. I’ll

pursue justice for the rest of my life.” ![]()

By Elyse Graham ’07

Clifford Geertz, a professor emeritus at the Institute for Advanced Study

who served as a visiting lecturer with the rank of professor in the University’s

history department for 25 years, died Oct. 30 at age 80. Geertz, an eminent

cultural anthropologist, was known for his research in Morocco and Indonesia.

![]()