From the Dec. 12, 2005, Princeton Weekly Bulletin

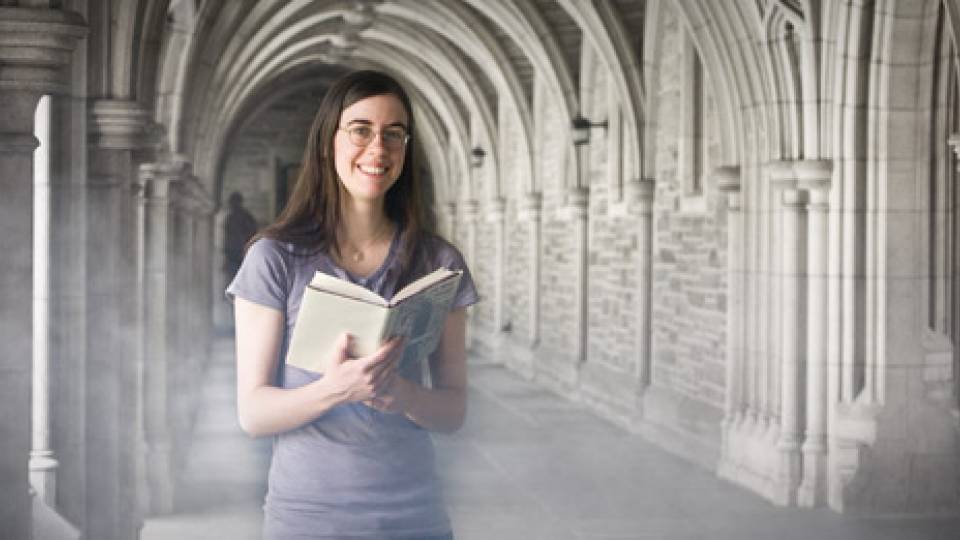

Scholars of great literature often are intrigued by questions that lie outside the pages of the text. For English professor Diana Fuss, one question that consumed her was: Where did my favorite writers write?

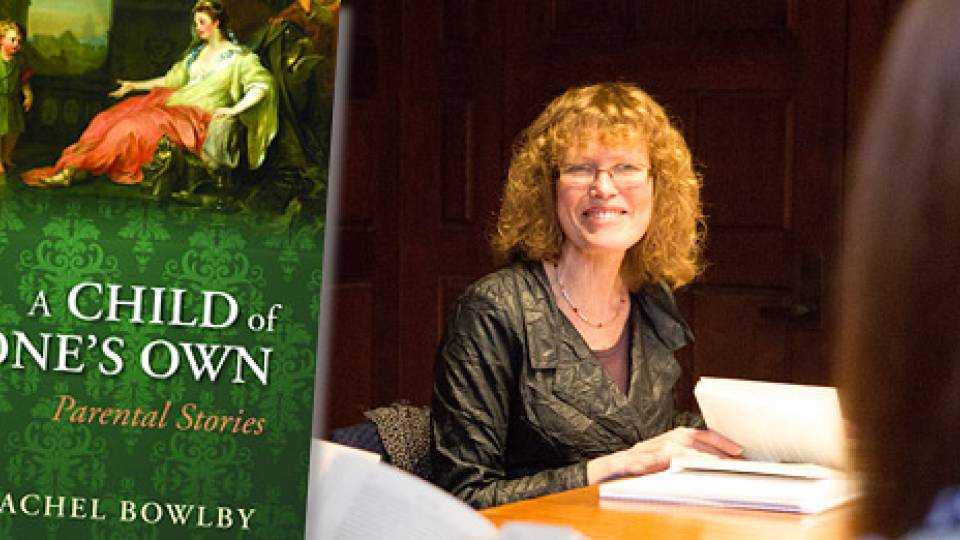

To find the answers, Fuss wrote “The Sense of an Interior: Four Writers and the Rooms That Shaped Them,” a study of the living and writing spaces of four well-known authors. Last month the volume, published by Routledge, was awarded the Modern Language Association’s James Russell Lowell Prize as the outstanding book of 2004.

In the book, Fuss describes the smoky ambiance of Sigmund Freud’s consulting room, the view from Emily Dickinson’s bedroom window, the inhospitality of Helen Keller’s house and the claustrophobic atmosphere of Marcel Proust’s bedroom.

In its citation the MLA said, “This richly generative book expresses and promotes a capaciousness of thought and mind, grounded by Fuss’ finely tuned ‘sixth sense’ and her unmatched capacity to recognize the power of space in the shaping of the imagination.” Fuss is the third Princeton professor to win the prize in its 36-year history.

She spent eight years doing research for the book, which included studying architectural site plans and elevations, finding period photographs and visiting each location. The work did have its perks: “I got to sit in Emily Dickinson’s cupola and lie on Freud’s couch — research doesn’t get better than that,” said Fuss.

The purpose of the book was to understand how the writers experienced their writing spaces. “When these figures inhabited these domestic interiors, what were they seeing, hearing, smelling and touching?” Fuss said. “What was the full sensory experience of inhabiting that space, and how did the domestic interior shape the acts of introspection that took place there?”

Fuss noted that Proust, who suffered from asthma, lived in a cork-lined room with heavy drapes to keep out natural light and air. The author of “Remembrance of Things Past,” a work suffused in sensory experience, “found it necessary to suspend the senses in order to write about them,” Fuss wrote.

Her findings corrected some dominant misconceptions. Dickinson, for example, has long been portrayed as a helpless agoraphobic trapped in a dark, coffin-like room in her father’s house. In fact, Fuss discovered that Dickinson’s corner bedroom had the best light and the best views of any in the house.

“It was a room that invested her with scopic power,” Fuss said. “Far from being confined in her room, she in fact was a kind of family sentinel.”

Fuss recreated the layout of Freud’s consulting room in meticulous detail by tracking down a photographer who had taken pictures of the room just before Freud fled Vienna in 1938. Fuss spent several weeks searching in London and Vienna for the photographer, Edmund Engelman, who was in his late 80s — and finally tracked him down living just a few blocks away from her apartment in Manhattan. Her timing was fortunate as Engelman died shortly after Fuss contacted him.

“He gave me all kinds of great details about the physical space of the office and how difficult it was to photograph because it was so cluttered with antiquities,” Fuss said. “The one space he was unable to photograph from was the space of Freud’s analytic chair, the seat of power as it were, because it could not be reproduced or occupied by anyone else.”

Fuss traveled to London’s Freud Museum to examine the analyst’s furniture — including the infamous ottoman couch on which his patients reclined — then went to his Vienna office, now empty, and pieced together what the room had been like.

“For the patient lying on the couch, surrounded by Persian carpets and wreathed in the smoke of Freud’s cigar, the room was a late Victorian fantasy of an opium den,” Fuss concluded.

Keller’s house, built especially for her, had been constructed with wall-to-wall carpeting and a sophisticated heating and air-conditioning system, both of which made the home especially inhospitable to someone who had neither sight nor hearing and relied on vibrations and air circulation to orient herself. “Keller and everyone around her were invested in showing that she lived an ordinary, normal life, like anyone else,” Fuss said. “Unfortunately the house was not conducive to the life that was lived there.”

Nurturing a love of literature

Fuss’ meticulous research for the book and her passion for her subject matter exemplify her style as a scholar and teacher, according to her students.

“With her contagious energy and excitement about the course material, she engages everyone in the classroom in the conversation,” said Amanda Teo, a member of the class of 1999. “For the longest time, my postgraduate plans involved law school, not graduate school. Professor Fuss nurtured in me a lifetime love of literature and inspired me to continue my literary studies beyond Princeton.” Teo is now pursuing her Ph.D. in English at Harvard.

Fuss, who has been teaching at Princeton since 1988, received the President’s Award for Distinguished Teaching in 2001. She has taught undergraduate courses on a range of topics in the areas of criticism and theory, American literature, poetry, and gender and sexuality. At the graduate level, she has taught seminars on the senses, the culture of death and contemporary theory. Former students praise her ability to bring clarity to complex material.

“When I worked as her teaching assistant for her ‘Introduction to Theory’ class, I was incredibly impressed by the way she was able to communicate difficult abstract material, including the work of Derrida, Irigaray and Foucault, in a way that excited and inspired, rather than alienated students,” said Karen Beckman, who earned a Ph.D. from Princeton’s English department in 1999 and is the Elliot and Roslyn Jaffe Assistant Professor of Film Studies at the University of Pennsylvania. “For me, Diana has established the standard by which I judge my own performance as a teacher and a scholar. I have a hard time meeting it — it’s a high one to match.”

Fuss currently is teaching a seminar that helps graduate students generate their dissertation topics. In addition, she has been acting chair of the English department since July. She relishes helping graduate students formulate their research topics.

“There’s nothing better than vicariously living through other people’s projects,” Fuss said.

Fuss lived through her own research for “The Sense of an Interior,” in a way — when she was halfway through the book, a realization struck her: Her own writing space was a slab of wood balancing on some rusting file cabinets, perhaps not the most nurturing place to compose her work.

“I went out and bought an Art Deco desk that reputedly was owned by a Hollywood mogul in the 1930s, in the hope that it would help me finish the book,” Fuss recalled. “It did.”