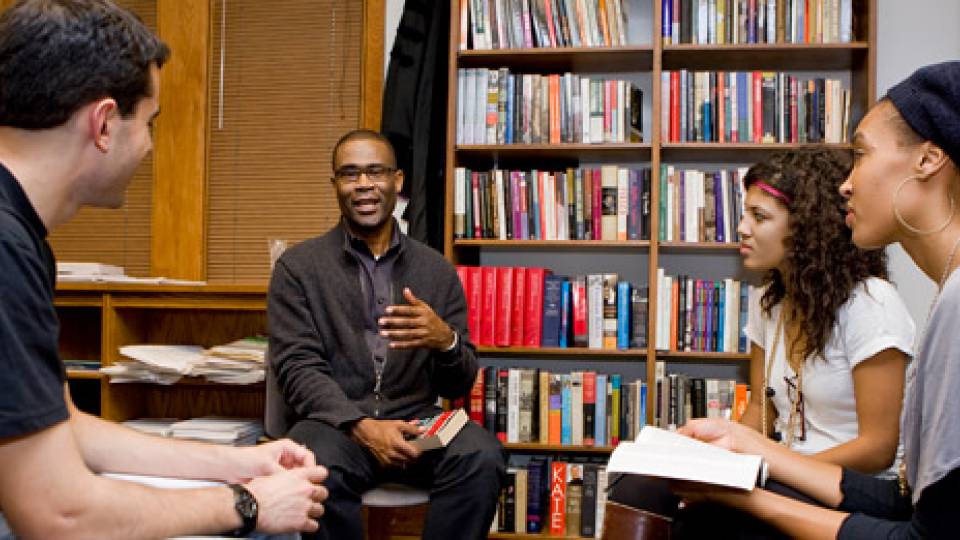

Religion professor Judith Weisenfeld began a recent discussion in her junior colloquium by playing three YouTube videos depicting darshan, the Hindu belief in divine communication through images of deities.

The 12 students in the seminar, "Religious Visual and Material Culture," watched as the screen showed a series of statues of Hindu gods. Weisenfeld explained the importance of the blissful interactions between viewers and religious objects in Hindu culture.

"That is their theological world," she said. "God is there."

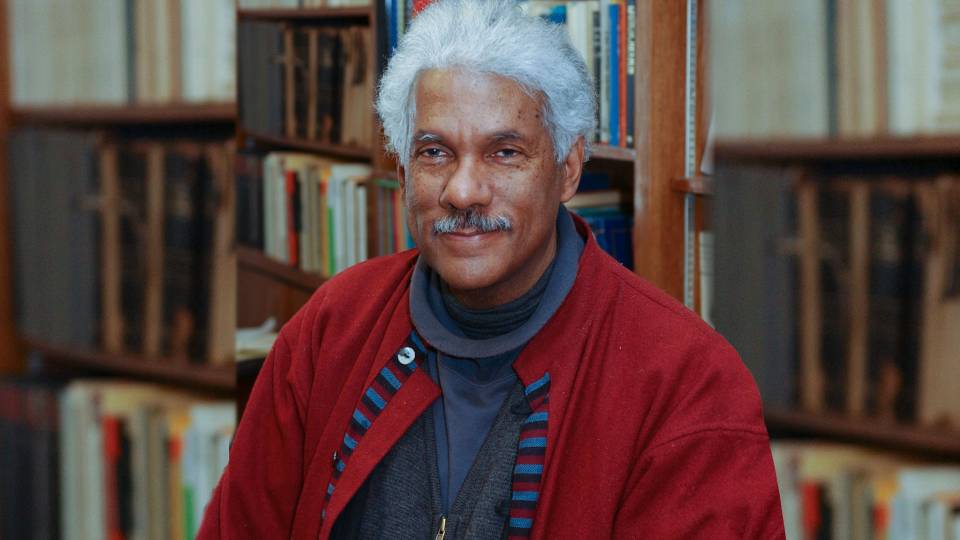

Religious images are recurring subjects of inquiry for Weisenfeld, a new professor of religion and an affiliated faculty member in the Center for African American Studies. Along with an interest in African American religious history, Weisenfeld is drawn to religious influences in activities that are not primarily religious, such as political and social activism, musical performance and film.

Since receiving her Ph.D. from Princeton in 1992, she has taught at Barnard College, Columbia University's Graduate School of Arts and Sciences and Vassar College. She also has published several books, including "Hollywood Be Thy Name: African American Religion in American Film, 1929-1949," released earlier this year.

Returning to Princeton was an easy choice, she said.

"This is a job of a lifetime at a really fantastic moment when the department is -- and to me has always been -- strong," she said. "And the new developments in African American studies are just more of the same," she added, referring to the expansion of the center's faculty and programs.

Her new colleagues, many of them familiar, have welcomed her back.

"I remember thinking that Judith was destined to become a leading scholar in the area of African American religion. It's no surprise that hunch turned out to be correct," religion professor Jeffrey Stout said. "With Judith and [new religion and African American studies professor] Wallace Best now joining a team that includes Albert Raboteau, Cornel West and Eddie Glaude, we now have an utterly remarkable capacity to reinterpret the African American religious heritage."

Taking an early interest

Growing up in a liberal New York City neighborhood, Weisenfeld encountered many social and political activists, and a local issue sparked her initial interest in religion. Weisenfeld's parents and their neighbors led an effort to desegregate her junior high school in Queens.

"I saw … an employment of civil rights era rhetoric that saw justice as in the abstract, the right thing to do, but also important to them in many cases because of their religious commitments," she said.

Questions about spirituality led Weisenfeld to take several religion courses after she enrolled at Barnard. One course, "Religions in Racially Stratified Societies," introduced her to African American religious history.

"I read a book called 'Slave Religion' by Albert Raboteau, and I remember the experience," she recalled one afternoon in her office in 1879 Hall, rising to retrieve her battered copy from a bookshelf. "It's in bad condition. On the back it says, 'Albert Raboteau is a professor of religion at Princeton University.' And when I began to think about graduate school, that was all I could think about."

At Princeton, Weisenfeld balanced her rigorous academic work with activities such as serving as a founding member of the Graduate Student Union (now the Graduate Student Government) and singing occasionally at Murray-Dodge Café.

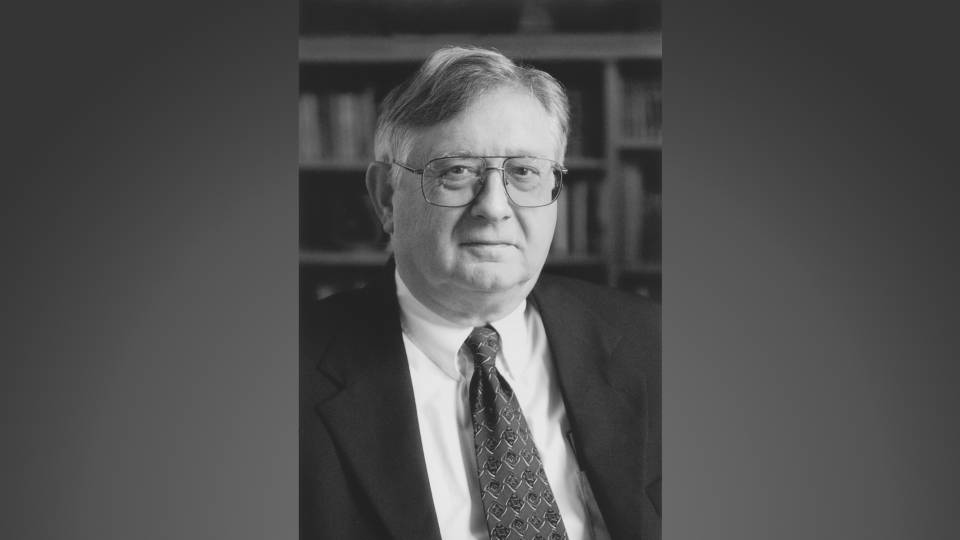

With Raboteau and John Wilson, the Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion Emeritus, as her mentors, Weisenfeld wrote her dissertation on the black women's branch of the YWCA in New York in the first half of the 20th century, examining the women's social and political activism in the context of urbanization and the civil rights struggle.

"I also think their goal was always to be a thorn in the side of white Christian women who claimed a certain kind of sisterhood and denied it at the same time," Weisenfeld said.

Her scholarship earned her a post at Barnard in 1991, and in 2000 she went to Vassar, where she rose through the religion department to become its chair.

In addition to setting new standards with her research, she was the "best chair ever," Vassar associate professor of religion Marc Michael Epstein said.

"I don't mean purely as a nuts-and-bolts administrator, but also as an intellectual force encouraging us all to read more, think more, listen more and share more," Epstein said. She was "a calm and conciliatory presence in the department and in the various programs to which she contributed, a leader who helped diverse colleagues cohere in close and productive ways, and a friend who was always available for consultation," he said.

Exploring religious themes in film

Toward the end of her time at Princeton, Weisenfeld began to develop an interest in film, and she organized a series of screenings of early African American films, many of which had religious themes.

That interest morphed into Weisenfeld's latest book, which was almost a decade in the making. In addition to analyzing films, reading press coverage and reviewing files from Hollywood's industry-wide censorship board, the Production Code Administration, Weisenfeld spent time in major studios' production archives in Los Angeles.

The book examines two kinds of films: "race movies," made by both African American and white production companies for black audiences; and Hollywood films with black casts.

Some of the race movies attempted to induce religious experience, while others showed a shrinking role for the church in an increasingly urban society, Weisenfeld said. The Hollywood films sought to "help" white audiences understand African American religious practices, and as a result, the entire race. They showed these worlds as simplistic, emotional and oversexualized, and the most spiritual characters often gave into temptation, Weisenfeld said.

"'They're wild and uncontrolled and uncontrollable, and so we should keep them on the farm and in their place,'" Weisenfeld said, summarizing the message of the films.

In her research for the book, Weisenfeld discovered the subject of her next project -- an actress, musician and activist named Eva Jessye. Weisenfeld is working on a critical edition of Jessye's 1927 book, "My Spirituals," which contains sheet music for songs as well as text about growing up in southeast Kansas among former slaves.

Jessye later wrote folk oratorios -- including a version of John Milton's "Paradise Lost and Regained" in Negro spirituals -- and sang at the 1963 March on Washington with her choir, combining her religious work and social activism.

"She thought the spirituals in particular could create a certain kind of understanding across racial barriers, and I think that's what drove her," Weisenfeld said. "[She also] really wanted to make the argument, a fascinating one, through some of her oratorios, that the classical texts of the West, whether they be music or literature, belong as much to African Americans as to anybody."

Weisenfeld plans to continue her work on Jessye and her other interdisciplinary interests in her new surroundings. She has maintained connections at the University over the years --participating in a Center for the Study of Religion project on women and religion in the African diaspora, lecturing in one of Stout's classes and speaking at multiple conferences at Princeton -- and is eager to work with old and new colleagues.

One of those colleagues is Valerie Smith, the director of the Center for African American Studies and Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature, who Weisenfeld has known since her graduate school days. In fact, Smith was a discussant at one of Weisenfeld's film screenings.

The passionate graduate student has turned into a leader in her field, Smith said.

"She has great programming ideas and a legendary ability to get things done, so her presence here is sure to enhance the already exciting schedule of events [the center] presents," Smith said. "And she is a brilliant teacher who will add an innovative set of courses to our curriculum."

Weisenfeld accepted the position at Princeton in part because she felt the University viewed the interdisciplinary nature of her work as an asset.

"There's an excitement about having people here who are amazing and fascinating and an enthusiasm about talking to each other about our work," Weisenfeld said. "So I'm really looking forward to that."