Nannerl Keohane (Photo by Brian Wilson)

Name: Nannerl Keohane

Title: Laurance S. Rockefeller Distinguished Visiting Professor of Public Affairs and the University Center for Human Values

Scholarly focus: Political philosophy, leadership, feminist theory. Her in-depth experience with leadership includes serving as president of Duke University from 1993 to 2004 and president of Wellesley College from 1981 to 1993. Among her current roles at Princeton focusing on leadership is her work as chair of the University's Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women's Leadership, which is issuing a report in the spring. Her latest book is "Thinking about Leadership," published in 2010 by Princeton University Press.

Why did you write a book on leadership?

I had been thinking about writing such a book since becoming president of my alma mater, Wellesley College, in 1981. One of my motivations for taking that job was scholarly and personal curiosity. Most political theorists (and political scientists in general) study leaders and power-holders from the "outside," looking at them from the perspective of citizens or subjects. I wanted to learn what being a leader of a major institution feels like "from the inside." And after I stopped being a president, I wanted to bring together my training and vocation as a political theorist with my experience as a leader in higher education to write a book that would illuminate both theory and practice.

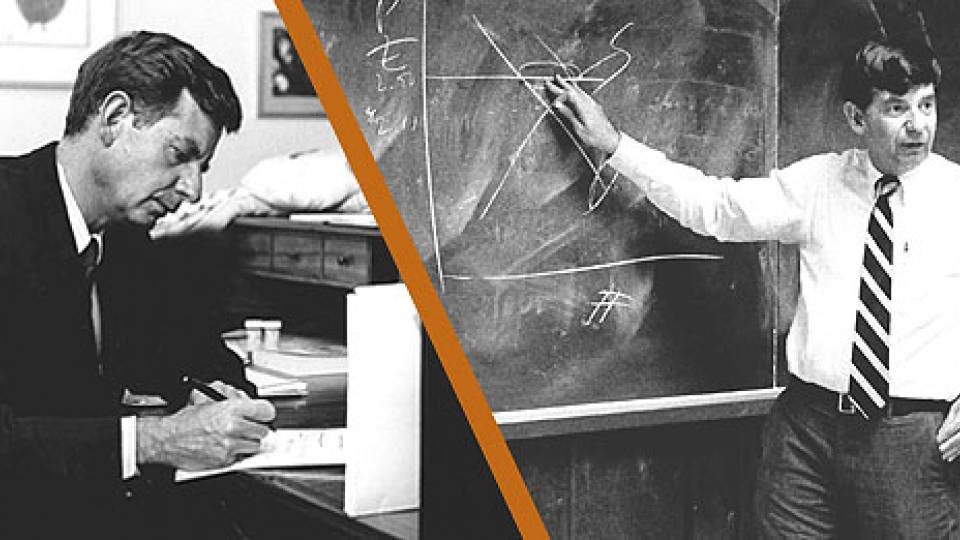

Nannerl Keohane said she wrote "Thinking about Leadership" to "illuminate both theory and practice" by bringing together her training as a political theorist and her experience as a leader in higher education. (Photo by Larry Levanti)

Where do leaders "come from?"

In my book, I paraphrase Maria's letter to Malvolio in Shakespeare's "Twelfth Night" on this topic: Some are born leaders, some become leaders (in the sense of preparing themselves for a post), some have leadership thrust upon them. In fact, some leaders -- George Washington, for example -- would fit any of these three categories. No single set of traits, qualities, skills, training or life experiences sets all leaders apart from anyone else. Instead, a combination of personal characteristics, situation and luck usually explains why any individual becomes a leader. Some individuals show qualities that prompt others to follow their guidance even when they are children; others develop such qualities over time. It does help to become familiar with instances of good leadership, to have thought about why people succeed or fail in accomplishing the tasks of leadership through studying examples. And it's very useful to have some experience in leading at lower levels or less demanding tasks before you take on a major post.

Some individuals find themselves in circumstances where their particular talents or ambitions are a good match with what is needed by a group of which they are a part, and others, who might have been equally successful as leaders, never find themselves in such a situation -- or if they do, decline to take advantage of it. And for some people, Machiavelli's "fortuna" is the key: Having the luck to be in the right place at the right time, with the right attitude, helps explain why quite a few people become prominent leaders. But as Machiavelli made clear, luck alone won't get you very far.

What is the most important quality for a leader? What are other valuable attributes?

Drawing on work by political theorists, philosophers and contemporary social scientists, I define judgment in the third chapter of my book as "a distinctive mental capacity or skill, a way of approaching deliberation and decision making that combines experience, intuition and intelligence." There are so many ways in which judgment matters -- making decisions, identifying good people to work with you, foreseeing problems, setting priorities.

In addition to judgment, other valuable attributes include knowledge of how to get and use information, courage, a healthy degree of self-awareness, stamina and a sense of humor. Knowing how to make decisions in a thoughtful and timely fashion, knowing when and how to compromise, are useful skills for any leader. I find Max Weber's essay "Politics as a Vocation" particularly helpful in thinking about this topic. He stresses that political leaders need a sense of responsibility, as well as both passion and proportion -- commitment to a cause beyond your own advancement, and a sense of detachment or distance that allows a leader to put things into perspective. As he says, passion and proportion or detachment are qualities that are not often found together. But in my experience, they are usually found in the leaders whom we most admire.

In her graduate-level course on leadership this semester, Keohane (left) invites discussion about what leaders do and what traits are important for successful leadership. Recently, she took time before class to talk with graduate students Karen Grissette (middle) and Christian Phillips (right). (Photo by Brian Wilson)

You describe the main task of a leader as determining or clarifying goals for a group of individuals. How can one become a "good leader" at this task?

Determining or clarifying goals involves understanding the complex parameters of a situation and the purposes you (and other members of the group) are trying to achieve. Bringing others along with you in the pursuit of these goals often involves rhetorical skills -- the skills of persuasion -- but before you get to that point, you should be able to listen to your followers and your advisers in order to formulate the goals in such a way that they will resonate with those you want to persuade. You don't get very far as a leader if you fall in love with the sound of your own voice. You have to find ways to get good information about what the members of your group care about and aspire to, and take this into account as you fold many different perspectives together (in a large organization, anyway). But you also have to be willing to make tough decisions and trade-offs in order to clarify goals that may be mutually exclusive or murky.

From your own experience in higher education, what is particularly important for a leader of a college or a university?

Leaders of an institution of higher education have to deal with some of the same issues as leaders of any large organization -- setting priorities and publicizing goals, recruiting and evaluating associates and subordinates, putting together budgets, and managing capital planning challenges. Leaky roofs are a problem whether your roof covers a high-tech physics lab, an august library or a consumer products warehouse. And the pressures of a high-powered job, the tough decisions, the travel schedule, the long days and weeks, are similar as well.

But leaders in higher education have no single bottom line to indicate success, and they are expected to be stewards of their institutional missions in ways that have no good analogues in for-profit enterprises. Transparency about goals and methods is especially valued. You need to be serious about consulting (and being seen to consult) people from all parts of the institution, especially the faculty. Instead of "marketing" the organization in an advertising mode, you need to be able to persuade major supporters and stakeholders (donors, alumni, foundations, government agencies, neighbors) that the institution is on the right path, that you are adhering to the basic values of your college or university and at the same time being creative, innovative and responsive to changing circumstances.

To inform their conversation about leadership, Keohane and the graduate students in her class explore classical political theory by studying Plato, Machiavelli and Max Weber, while also drawing on current "leadership literature" and case studies of decision making. Pictured from left to right are: Keohane, Karen Grissette, Brian Nafziger, Christian Phillips and Shawn Powers. (Photo by Brian Wilson)

With much of your career spent on college campuses, what do you regard as most significant for young people to learn about leadership? What do you most want to relay to them?

I hope that college-age students will look carefully at leaders they admire (as well as leaders whose values and actions they question) so that they form a mental stock of examples of both good and bad leadership. Keeping up with current events is part of this: What should we think about what's happening now in Egypt and Libya and Tunisia and Bahrain, and what does this tell us about leadership as a human activity? How do we understand contemporary conflicts in Washington, D.C., about the appropriate course for our country, and what can we learn about leadership from the various activities of the visible leaders in all three branches of government? But it's worth looking carefully at leaders right around you, at leadership on campus, too.

Learning about historical examples of good (or bad) leaders is very helpful. Studying the career of an exemplary leader like Nelson Mandela can inspire and sharpen the leadership instincts of young people; learning about the complexities of an admired but flawed leader such as Lyndon Johnson can deepen your understanding both of the opportunities and challenges of leadership. It is also a good idea to keep in mind, as you study literature or art, that leadership and power are often topics chosen by writers and artists in the past. Reflecting on these examples can deepen your own understanding of leadership.

Finally, I hope students will stop occasionally during these years and reflect on what leadership is all about. Having some responsibilities yourself is part of this, and that doesn't have to mean being the president of a major campus organization (although such posts are very useful experiences for many reasons, including preparation for future leadership). Most Princeton students are engaged in some kind of leadership, in the sense of facilitating the work of an organization they care about, setting the agenda for groups of friends, or bolstering the morale of teammates on the playing field. These are formative experiences, and they can provide the groundwork for more visible leadership later on.

You note that women, like men, display a wide range of leadership styles, although women tend to be more nurturing. In an educational setting, what might be beneficial for women to explore in their own leadership styles and goals?

In the fourth chapter of my book, I wrestle with the question whether women lead differently from men, and give a guarded answer. It's surely the case that not all women lead in the same way, and it's definitely not the case that all women leaders are particularly nurturing (think of Margaret Thatcher or Golda Meir). We don't yet know how much impact hormones or genes have on our behavior as leaders. But we do know that childhood socialization has a deep influence on how adults behave, and that girls and boys are routinely socialized in different ways (by popular culture, if not by their parents) in any culture. So it wouldn't be surprising if women (and men) reflect these background experiences when we become leaders. But each individual leader does so in her own way.

During the college years, I encourage women to trust themselves and their own abilities, and test out their leadership capacities in a variety of ways, rather than accepting stereotypes that may seem to require them to behave in ways that don't feel personally right for them. I hope they will support one another, mentor one another, encourage one another to take on significant posts and projects, whatever the cause they care about. Women are sometimes reticent to step forward for leadership posts, for a variety of reasons; but we have multiple examples of superb women leaders of all ages, and I would encourage women to "go for it!" when they find something that they care about, taking on leadership responsibilities in order to make a difference. Women are generally less self-confident than men, and college is a good place to develop your self-confidence and prepare yourself for making a difference in the world outside.

You say it is important for a leader to occasionally adopt a stance of the "outsider." Why should a leader do this and how?

In using this term, I was referring to three things, each suggested by one of my favorite political theorists.

First, to the alternation between leaders and followers, best captured by Aristotle's insight about ruling and being ruled: He said that learning how to follow is one of the best ways to prepare to become a leader, and that leaders in a constitutional democracy should recall that their terms will be up before too long and they will have to go back to following, so they should keep in mind the interests of followers as they make decisions -- the situation of followers is one that they have shared before, and will share again. You should thus think about the impact of what you do on those "outside" your job.

In a similar vein, I had in mind the value of looking at leaders from the perspective of those most affected by their work, in Machiavelli's sense. He uses the image of the landscape artist painting the lofty hills, better able to see the whole thing than someone who is actually at the top of the mountain. I think he meant that being "outside" gives you a fuller sense of the whole situation and context than you can have when you are caught up in details and absorbed by power. You can achieve this, as a leader, partly by being sure to get good information from a variety of sources and listening to people from different backgrounds rather than only those who tell you what they think you want to hear.

And finally, I was referring to Pascal's sense in one of his "Pensées" of being an impersonator, which means that you should be aware that as a powerful leader of a major institution, you are in some ways playing a role, and your job is to play it as well as you can. You should avoid becoming so closely identified with the office that you define it as your own personality writ large.

I develop all these points in the book, and from this I hope that readers will get a sense of why I think that both being "inside" and "outside" the role of leader is a good way both to lead and to understand what leaders do.

What have you most enjoyed about being a leader?

I have enjoyed the opportunity to know many different kinds of people who are involved in one way or another with an institution like Wellesley or Duke -- the trustees and the gardeners, the librarians and the student government officers, the housekeepers and the major donors, the faculty in all disciplines. I have enjoyed being the "symbol" of institutions that I care about deeply; walking down the aisle of the chapel at baccalaureate or convocation and knowing that I was regarded as the representative of a historic and worthy place and a set of goals and aspirations that many others share. I have enjoyed the opportunity to articulate goals and persuade others to follow me, as well as the strategic give-and-take that precedes the formulation of these goals. I liked having power, in the sense of being able -- after consultation, conversation and reflection -- to make the final decision, to say, "Here's what we are going to do," and have lots of people go off and do it.