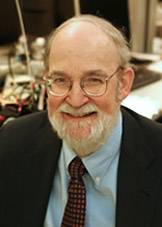

Bradley Dickinson, a professor of electrical engineering at Princeton University who helped shape one of the engineering school's fundamental design courses, died of cardiac arrest Jan. 22 at Capital Health Regional Medical Center in Trenton. He was 63.

Dickinson, who joined the faculty after receiving his Ph.D. from Stanford University in 1974, was an expert in video and image processing, signal processing and artificial neural networks. In addition to teaching, he served as the associate dean for academic affairs in the School of Engineering and Applied Science from 1991 to 1994.

While serving as associate dean, Dickinson worked tirelessly to support students from underrepresented backgrounds at the engineering school, said Peter Bogucki, the school's associate dean for undergraduate affairs. Dickinson developed a program funded by the National Science Foundation to support research internships, and helped to establish the William Randolph Hearst Endowed Scholarship Fund to enable several engineering students each year to pursue their studies in the freshman and sophomore year without the burden of a campus job.

"In addition to his service as a faculty member in electrical engineering, his service to the school was pretty crucial," Bogucki said. By striving to increase the University's outreach to underrepresented students, he "contributed to programs that are now established on a University-wide scale."

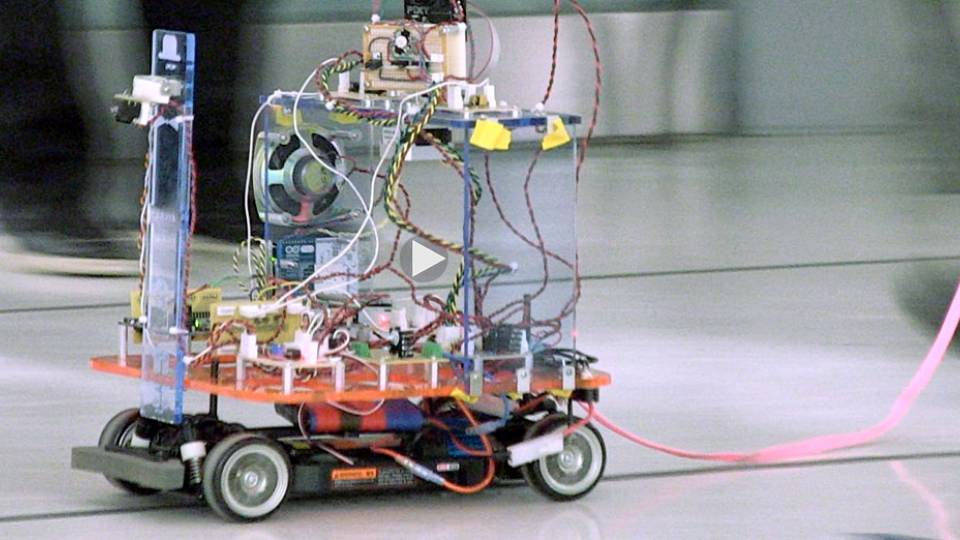

For many years, Dickinson taught "System Design and Analysis," a required course for electrical engineering majors. Known informally as "car lab," the course has become a rite of passage in the department, both for its demanding schedule and challenging subject. In it, students build and program computer-controlled cars to perform tasks such as reverse parking or avoiding an obstacle on a track.

"It's important that the students understand that engineering is not just textbook math and physics," said Peter Ramadge, chair of the Department of Electrical Engineering. "Dealing with the real world is a different challenge." Ramadge said that over the years, students developed a body of knowledge about the best techniques to meet the course requirements for car lab, so Dickinson introduced innovations to the course content to keep the materials challenging.

Ryan Corey, a senior in electrical engineering, said the course was a chance to apply the skills learned in class in a very concrete way. "The class is notoriously difficult, and it can be painful as a rite of passage, but you come out of it really knowing how electronics work and how embedded systems work," he said. The course brings together large groups of classmates and sets them to solve technically difficult problems. "The cohesiveness of the department in large part comes from that class," Corey said.

Dickinson was born in St. Marys, Pa. He received his bachelor's degree from Case Western Reserve University and his master's and Ph.D. from Stanford. He was appointed as assistant professor of electrical engineering and computer science at Princeton in 1974 and promoted to professor of electrical engineering in 1985. In 1987, he was elected as a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

Author of the book "Systems: Analysis, Design and Computation" (1991), Dickinson held two patents in video data compression. He was a founding co-editor of the journal Mathematics of Control, Signals and Systems.

A team player

"Dickinson had a broad range of interests, and he was always willing to apply his skills in needed areas," said Bede Liu, professor of electrical engineering at Princeton and a colleague of more than 30 years.

"What I will remember was that he was always willing to help out when something needed to be done," Liu said. "He was always willing to pitch in."

Dickinson served for many years as the electrical engineering department's undergraduate representative and was involved in departmental accreditation reviews. He was instrumental in introducing Matlab, a computing tool used by engineers and scientists, to Princeton.

"There were a number of people who contributed, but Brad was the person at Princeton who made sure it happened," Ramadge said. "He was a team player."

Colleagues described Dickinson as a thoughtful man but not a shy one.

"He had a good but dry sense of humor," Ramadge said. "If you listened carefully, you picked up the joke."

Charles Boncelet, whose doctorate was supervised by Dickinson, said he had a low-key style of instruction.

"He did not look over your shoulder all the time," said Boncelet, who is now a professor in the University of Delaware's electrical and computer engineering department. "He would give the students a problem to work on and let them work on it."

Boncelet said that Dickinson enjoyed working with students and that, after work, he and Dickinson would often go out for a game of darts.

Dickinson is survived by his wife of 28 years, Colette, a 1975 Princeton alumna; his son, James, a 2006 Princeton alumnus; and his daughter, Betsy. The funeral service will be held Monday, Jan. 30, at Kimble Funeral Home at 1 Hamilton Ave. in Princeton. Visitation will start at 10 a.m. and the funeral service will begin at noon. Burial will follow at Princeton Cemetery at the intersection of Witherspoon and Wiggins streets.

A campus memorial service will be planned.