Researchers have identified a benign bone tumor in the rib of a young Neandertal who lived about 120,000 years ago — by far the earliest bone tumor ever identified in the archaeological record. The identification, by a team that included two researchers affiliated with Princeton University, could offer a new clue to the relationship between Neandertals and modern humans.

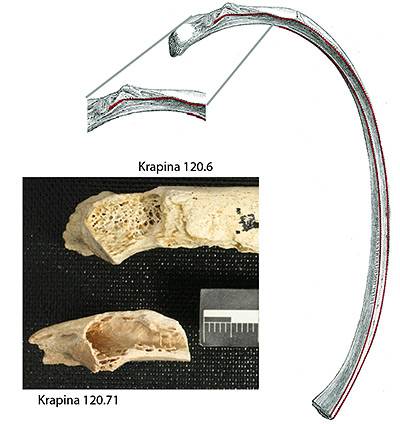

Researchers believe the bone fragment that contained the tumor was part of a left rib, shown in an illustration. In the photo, the fragment with the tumor is shown below a healthy bone for comparison. (Photos of bone courtesy of L Mjeda, Zagreb; comparisons, Janet Monge)

The identification — in a bone fragment uncovered in the archaeological cave site of Krapina, Croatia — was announced June 5 by an international research team that included Princeton anthropology professor Alan Mann and Janet Monge, a visiting associate professor of anthropology at Princeton and associate curator and paleoanthropologist at the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

Other members of the research team were Morrie Kricun of the University of Pennsylvania, Jakov Radovcic and Davorka Radovcic of the Croatian Natural History Museum, and David Frayer of the University of Kansas.

Details of the tumor confirmation are available in the paper "Fibrous dysplasia in a 120,000+ year old Neandertal from Krapina, Croatia" in the online scientific journal PLOS ONE.

Bone tumors are exceptionally rare finds in the evolutionary fossil and archaeological records of human prehistory, with the earliest known instances, before now, dating to 1,000 to 4,000 years ago. Such bone tumors are rare in modern populations.

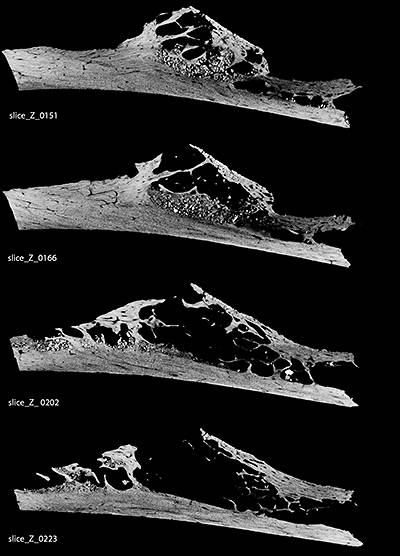

A CT scan that offers several views of the bone fragment shows deterioration related to the tumor. (Courtesy of GW Weber, University of Vienna, Austria)

"One of the important goals of the investigation of our ancestors is to discover aspects of their biology and behavior that provide insights into our present condition," Mann said. "The discovery of this benign tumor in this collection documents the presence of this pathology well back into our biological history."

Mann, a physical anthropologist, has focused his research on fossil remains of australopithecines and Neandertals to understand human growth and development. He began teaching at Princeton as a visiting professor in 1986 and joined the faculty in 2001.

Using imaging technology, the researchers identified a fibrous dysplastic neoplasm — today, the most common form of benign bone tumor in humans — located on a Neandertal left rib fragment that measured 30 mm (4.5 inches) long. Judging by the size of the rib fragment, at the end of the rib that joins to the vertebrae, the rib belonged to a young male Neandertal, probably in his teens. Though he died young, and fibrous displasia is a developmental disorder of bone, there are no other known fossils that can be attributed to this individual, and there is not enough evidence to determine if the tumor was the cause of or contributed to his death, Monge said.

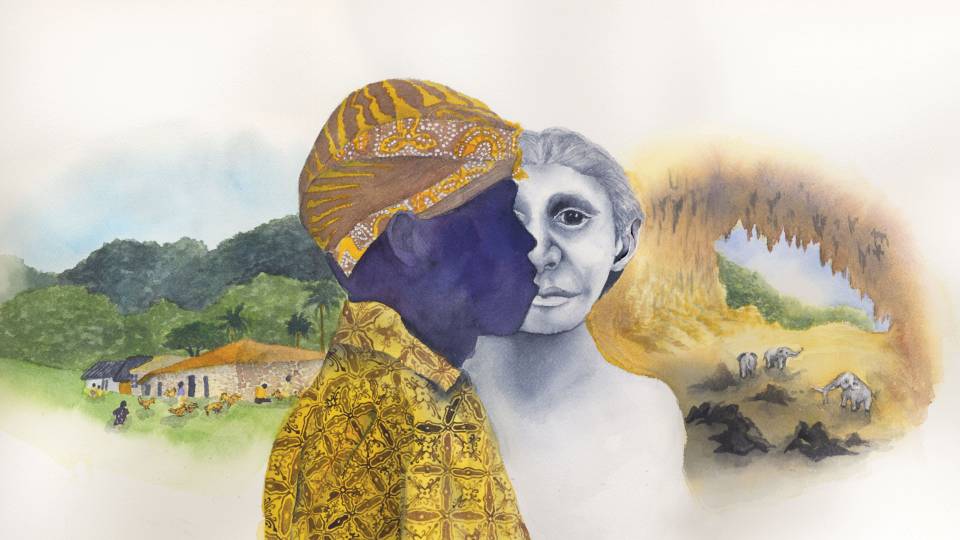

The confirmation of the tumor may have implications for scholars studying the relationship between Neandertals and modern humans, Monge said.

"This tumor may provide another link between Neandertals and modern peoples, links currently being reinforced with genetic and archaeological evidence," she said. "Part of our ancestry is indeed with Neandertals — we grow the same way in our bones and teeth and share the same diseases."