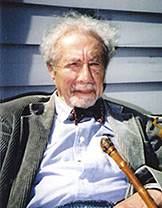

Arthur Szathmary, a Princeton University professor emeritus of philosophy, died of natural causes July 1 at his home in Princeton, N.J. He was 97.

Over the course of his nearly 40 years at the University, Szathmary's work probed the philosophical significance of art and the relations between art and philosophy as modes of understanding human experience. He also concentrated on the principle of aesthetic criticism of art and was intrigued by how art enables people from different cultures to understand each other. He retired from Princeton in 1986.

Paul Benacerraf, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus, who earned his bachelor's degree and doctorate from Princeton in 1952 and 1960, respectively, and served twice as department chair, says he felt Szathmary's influence both as a student and a colleague.

"Arthur was an important member of the Princeton faculty," Benacerraf said, "partly because he was one of very few with his particular sensibilities and interests — a broad and deep interest and competence in the arts and how to think about them — but especially because of his personal kindness and openness."

Benacerraf said Szathmary helped him find a place for himself at Princeton in the early 1950s. "As an undergraduate, I wandered around pretty lost for a couple of years, until I found Arthur, and although my philosophical interests eventually diverged from his, he had been the link that enabled me to think that I could make it at Princeton — that there was a place for me here after all."

Szathmary joined the Princeton faculty in 1947. He earned his bachelor's, master's and doctoral degrees from Harvard University, the last in 1942. Working with Japanese prisoners as a Navy intelligence officer during World War II sparked his interest in Japanese culture.

His commitment to the arts led to his appointment as chair of the Creative Arts Committee from 1958 to 1967, which oversaw the Creative Arts Program. Under Szathmary's leadership, along with program director R.P. Blackmur, a succession of poets, writers and critics taught in the program. Szathmary also served as a senior fellow in the humanities.

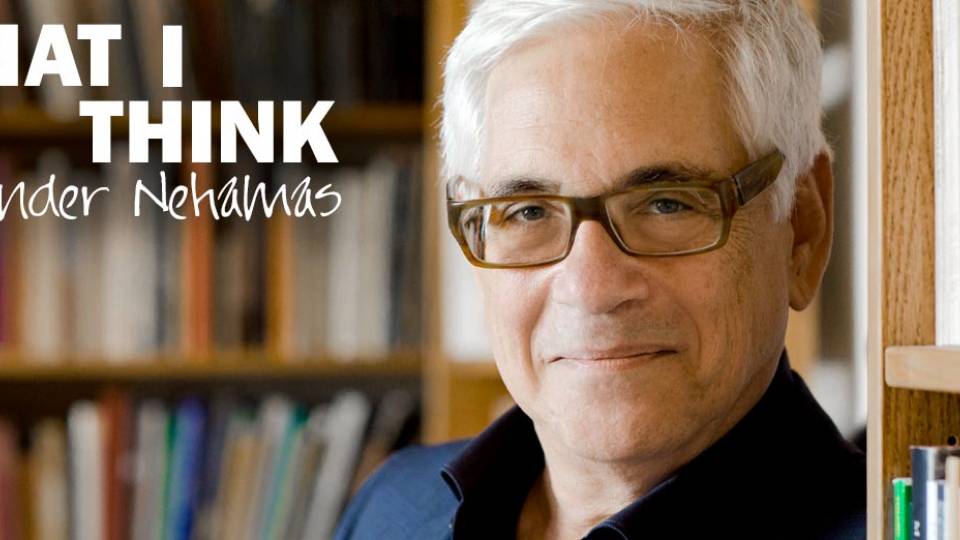

"His great contribution was in his teaching and his close personal relations with his students," said Alexander Nehamas, the Edmund N. Carpenter II Class of 1943 Professor in the Humanities and professor of philosophy and comparative literature. Nehamas met Szathmary as a graduate student in the late 1960s, when he led the precept for Szathmary's undergraduate course on the philosophy of art.

"His courses, especially the undergraduate courses he taught, attracted large groups of students, including, among others, the painter Frank Stella," Nehamas said. "He was an infectiously enthusiastic teacher, with high standards, but always profoundly generous, encouraging and full of good will."

Szathmary's impact on his students often lasted long after they left Princeton. In 2008, Gregory Callimanopulos, a member of the Class of 1957 and a noted art collector, donated the first Picasso painting to enter the Princeton University Art Museum's collection, "Tête d'homme et nu assis ("Man's Head and Seated Nude"), in honor of Szathmary.

While earning a master's in architecture and urban planning at Princeton in the mid-1970s, Jeffrey Ng, now an architect based in Fairfield, Conn., took two courses on the philosophy of art taught by Szathmary. Remaining friends over the years, their last visit took place just before Szathmary's 97th birthday in April.

"As an architectural graduate student, I found his courses particularly relevant by offering a philosophical context for my studies," Ng said. "Like a modern day Socrates, he taught us to be skeptical of conventional thinking of art and aesthetics and even of accepted theories and modes of analysis. The world has suffered a great loss of a wise, gentle and inspiring teacher."

Szathmary is survived by his wife, Lily Hayeem; his brother, Bill Dana; and his children, Robert and Helen.

Both the family and the Department of Philosophy are planning memorial services.