Practice doesn't make it perfect.

Deliberate practice may have less influence in building expertise than previously thought, according to an analysis by researchers at Princeton University, Michigan State University and Rice University.

Scientists have been studying and debating whether experts are "born" or "made" since the mid-1800s. In recent years, deliberate practice has received considerable attention in these debates, while innate ability has been pushed to the side.

The recent focus on deliberate practice is due in part to the "10,000-hour rule" coined in Malcolm Gladwell's 2008 book "Outliers," which says that amount of practice is the key to success in any field.

The new research, from psychological scientist Brooke Macnamara of Princeton and colleagues, offers a counterpoint to this recent trend, suggesting that the amount of practice accumulated over time does not seem to play a huge role in accounting for individual differences in skill or performance in domains including music, games, sports, professions and education.

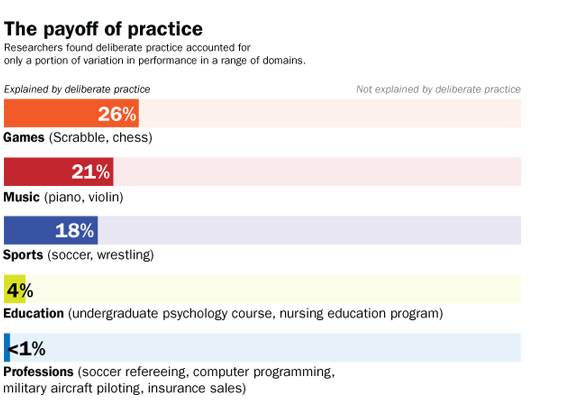

Overall, deliberate practice — activities designed with the goal of improving performance — accounted for only about 12 percent of individual differences observed in performance.

"Deliberate practice is unquestionably important, but not nearly as important as proponents of the view have claimed," said Macnamara, who received her Ph.D. from Princeton in June. As of July 1, she is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology at Case Western Reserve University.

The new analysis by Macnamara, David Z. Hambrick of Michigan State and Frederick Oswald of Rice is the subject of their paper, "Deliberate Practice and Performance in Music, Games, Sports, Education and Professions: A Meta-Analysis," published online Monday, July 1, by the journal Psychological Science.

The researchers scoured the scientific literature for studies examining practice and performance in the different domains.

Of the many studies they found, 88 met specific criteria, including a measure of accumulated practice and a measure of performance, and an estimate of the magnitude of the observed effect. The selected studies had a total sample size of 11,135 participants. The researchers took those studies and performed a "meta-analysis," pooling all of the data from the studies to examine whether specific patterns emerged.

Nearly all of the studies showed a positive relationship between practice and performance: the more people reported having practice, the higher their level of performance in their specific domain.

The domain itself seemed to make a difference. Practice accounted for about 26 percent of individual differences in performance for games, such as chess and Scrabble; about 21 percent of individual differences in music, such the piano and violin; and about 18 percent of individual differences in sports, such as soccer and wrestling.

But it only accounted for about 4 percent of individual differences in education, such as an undergraduate psychology class, and less than 1 percent of individual differences in performance in professions, such as soccer refereeing and computer programming.

Furthermore, the findings showed that the effect of practice on performance was weaker when practice and performance were measured in more precise ways, such as using practice time logs and standardized measures of performance.

"There is no doubt that deliberate practice is important, from both a statistical and a theoretical perspective. It is just less important than has been argued," Macnamara said. "For scientists, the important question now, is what else matters?"

Macnamara and colleagues speculate that the age at which a person becomes involved in an activity may matter, and that certain cognitive abilities (such as working memory) may also play an influential role. The researchers are planning another meta-analysis focused specifically on practice and sports to better understand the role of these and other factors.

David Lubinski, a professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University who has studied talent identification and development, said the researchers' work highlights the importance of accounting for ability, commitment and opportunity to explain individual differences in human performance.

"Although overly stressing one of these critical components may attract attention, the authors show why all three are required for a comprehensive understanding of human performance," he said. "The view that essentially anyone can do essentially anything is not scientifically defensible."