Despite the threat of a global antibiotic-resistance crisis, the worldwide use of antibiotics in humans soared 39 percent between 2000 and 2015, fueled by dramatic increases in low-income and middle-income countries, according to a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The study, which analyzed human antibiotic consumption in 76 countries, is the most comprehensive assessment of global trends to date.

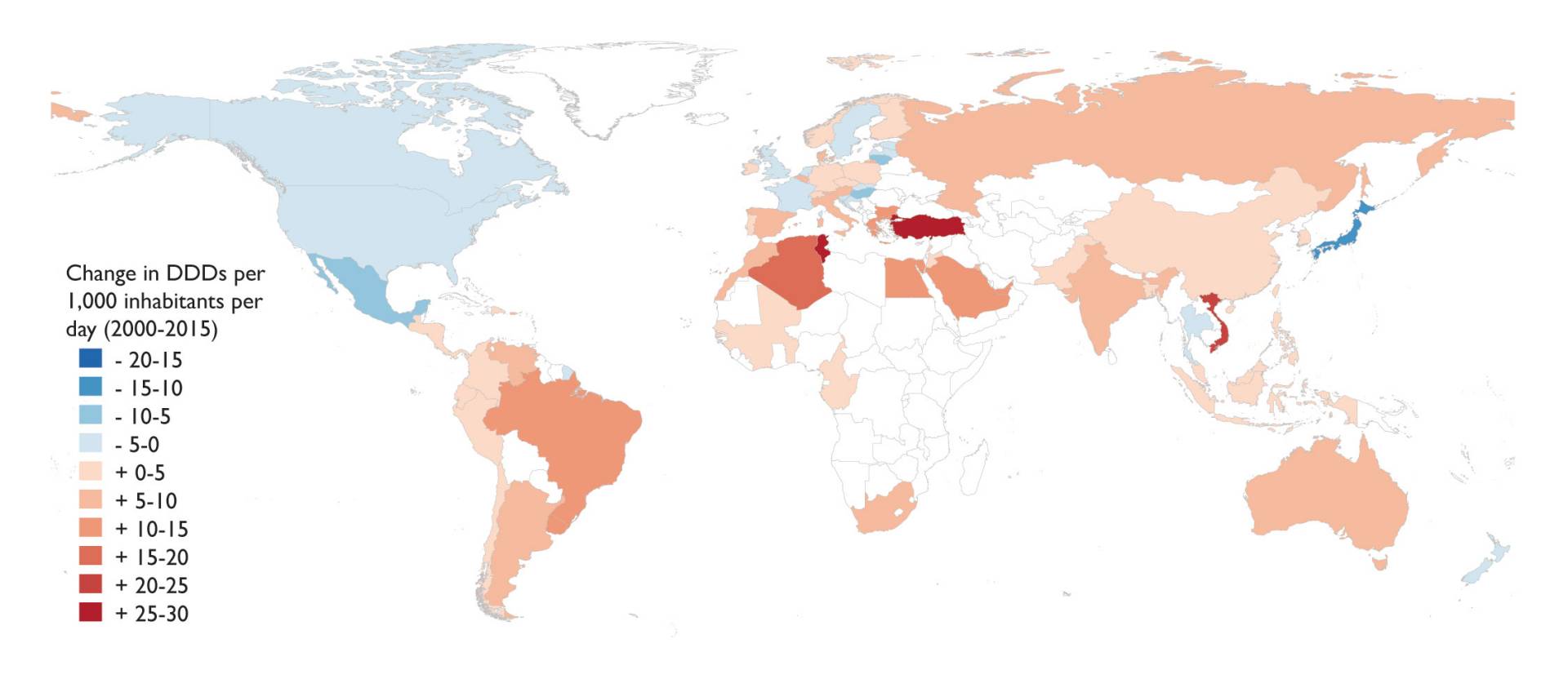

Researchers found that the worldwide use of antibiotics in humans soared 39 percent between 2000 and 2015, particularly in low- and middle-income nations. The map above shows increases in defined daily doses (DDDs) — a statistical and standardized measure of drug consumption — per 1,000 inhabitants. Red shades indicate an increase in antibiotic consumption, while blue shades indicate a decrease.

Researchers from the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP), Princeton University and the Princeton Environmental Institute (PEI), ETH Zurich and the University of Antwerp found that antibiotic consumption rates between 2000 and 2015 increased worldwide from 11.3 to 15.7 defined daily doses per 1,000 inhabitants per day. Defined daily doses are a statistical and standardized measure of drug consumption that represent the assumed average daily maintenance dose for a drug used for its main indication in adults. Altogether, the total global use of antibiotics in humans was estimated to be 35 billion defined daily doses in 2015, a 65 percent increase from 2000.

Antibiotic use in low-income and middle-income countries, antibiotic use — particularly of broad-spectrum penicillins — increased by 114 percent in the same 15-year period, spurred by economic and population growth. Some of those countries had consumption rates that surpassed those of high-income countries, but many still have considerably lower per-capita levels of anitbiotic consumption than high-income countries due to limited access. The United States remained one of the largest consumers of glycylcyclines (tigecycline) and oxazolidinones (linezolid).

Despite the rising rates of antibiotic use worldwide, the study results suggest that reducing antibiotic consumption is possible, the researchers said. Consumption in high-income countries actually fell slightly over the study period. In addition, the considerable variation in per capita use across high-income countries suggests that there are lessons to be learned.

"Finding workable solutions is essential, and we now have key data needed to inform those solutions," said corresponding author Eili Klein, a CDDEP researcher and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Johns Hopkins University who received his Ph.D. in ecology and evolutionary biology from Princeton in 2012. "Now, more than ever, we need effective interventions, including stewardship, public education, and curbing overuse of last-resort antibiotics."

Antibiotic resistance is a global health problem; when it emerges in one place, it quickly spreads to other parts of the world. The study underscores the need for consistent global surveillance of antibiotic resistance and policies to curtail unnecessary antibiotic use. The loss of effective antibiotics is driven in large part by antibiotic consumption, most of which is inappropriate and does nothing to improve health, the researchers said. Bacterial resistance to antibiotics can be detrimental to people in developing nations that actually need improved access to antibiotics to help fight their higher rates of illness and death caused by infectious diseases.

"We must act decisively and we must act now, in a comprehensive manner, to preserve antibiotic effectiveness," said co-author Ramanan Laxminarayan, senior research scholar in PEI and director of CDDEP. "That includes making solutions that reduce consumption, such as vaccines or infrastructure improvements, particularly in low-income and middle-income countries. New drugs can do little to solve the resistance problem if these drugs are then used inappropriately, once they are introduced."

The United Nations General Assembly recognized the global threat of antibiotic resistance in 2016, yet little action has been taken since then, the researchers said. Social norms and weak regulations are driving antibiotic resistance, said co-author and PEI associated faculty Simon Levin, Princeton's James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology and director of Princeton's Center for BioComplexity.

People feel they need antibiotics, doctors feel pressured to prescribe them and governments do little to control the supply, said Levin, who is working with Laxminarayan on a project through the James S. McDonnell Foundation to examine the role of social norms in driving antibiotic overuse.

"In many countries, antibiotics are not regulated, or weakly regulated, and antibiotics are easily available over the counter," Levin said. "No doctor is likely to be sued for prescribing antibiotics when they are not needed, but lawsuits would be more likely if a child with an ear infection didn't get antibiotics and had a complication. Such issues are in part responsible for the overuse of antibiotics when undergoing dental work, although this can be ascribed in part to risk avoidance and risk-averse behavior by doctors and patients alike."

Rachel Heckscher of CDDEP and Morgan Kelly of PEI contributed to this report.