It was a colony of Great Britain until 1948 when independence was achieved. But in the 1960's, the country was taken over by a military junta that cut it off completely from the rest of the world: no one was allowed in or out for over 30 years. Then, a few years ago, the dictators decided they could use the money that tourism would bring, and they began to allow in a limited number of tourists, but only as members of tour groups. Just recently, they went further and opened the country to a limited number of independent travelers who can get past a grilling interview process. The paranoid leaders try to keep out all writers and lawyers. So Susan claimed to be a housewife and I claimed to be a biologist.

From the moment of our arrival, we felt like we had passed into the Twilight Zone. Every city has two names -- the old one and the new one that the dictators have imposed. So the capital Rangoon has become Yangon. Corruption is everywhere, and so is paranoia. The immigration officer readily accepted our bribe of $10 to let us pass into the country without giving a $200 entrance payment to the government. As we waited in the transit lounge for a plane to Mandalay, a smiling government agent kept his eye on us. We boarded the small plane and watched the flight officer determine the flight pattern with a pencil and paper since the domestic airlines have no computers. We arrived safely in Mandalay, found a hotel, registered with the police (as all foreigners are required to do), and went to sleep.

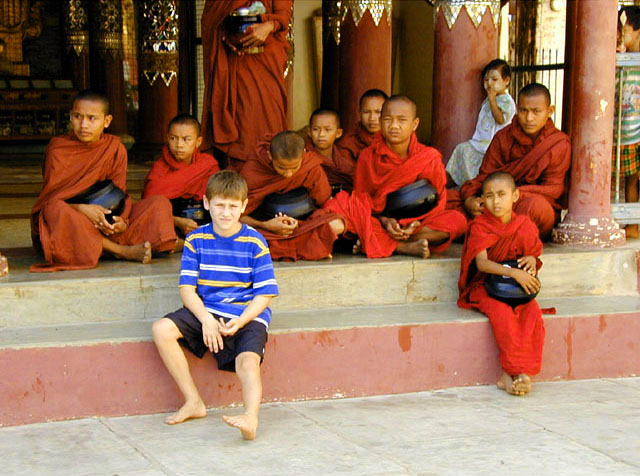

The next morning, we took an hour long walk up Mandalay Hill to see a famous Buddhist Temple at the top. For the first part of the walk, we were tailed by a government agent who didn't even try to hide from us. Halfway up the hill, the monk shown in the picture below, approached us and told us that only 7 months earlier, he had learned how to speak English. He kindly asked if he could practice by talking to us. We were more than happy to agree, and for the next three hours, our monk stayed by our side as we visited various temples and shrines. He even taught Max how to count to 10 in the Burmese language. Meanwhile, the government agent had disappeared.

By late afternoon, we had decided to move on to another part of the city and hopped on to the most common form of local transport called a trishaw, which is a bicycle connected to a two-seat sidecar in which passengers face forward and backward. Max, Rebecca, and Ari (sitting on the back wheel behind the driver) went onto the one shown below, and Susan and Lee took another. Our monk told us that trishaw drivers were sleazy characters not to be trusted, but we decided to go on them anyway. As soon as we started moving, our driver whispered to us that our monk really wasn't a monk, but was a government spy in disguise. Suddenly, Susan and I realized that our monk had behaved in ways that were unbecoming of a true monk; his fluency in English was far too great for someone who had just learned the language seven months earlier; and our previous tailing agent had left the scene just as our monk had picked us up. But we couldn't be sure. Who was telling the truth?

This is a very poor country without running water, phones or electricity in most places. Motor vehicles are very scarce and in each city and town a different solution to the transportation problem has evolved. The next city, we visited, called Pyin U Lwin, was up in the hills with a cooler climate, and the streets were filled with horses and buggies like the one shown below (left over from the British era). As you can see in both this photo and the ones above and below, the men all wear a traditional form of clothing called a longyi, which is like a wraparound patterned skirt.

For transportation between towns and cities, people are dependent on "buses," like the two shown below. The buses are actually modified pickup trucks with rows of seats on either side of the truck bed. There are so few buses that they are always overloaded with people sitting on the roof and hanging off the back and sides. These buses are on a three hour journey between Pyin U Lwin and Mandalay.

Although this may look like a scene from 19th century America, it is actually an encampment of covered wagon homes belonging to a present-day nomadic Burmese tribe.

The women come down to the river each day to wash their clothes and dishes and, at the same time, bathe with their children. In the distance, a mile away, you can see the ruins of an enormous partially completed monument that was meant to rival the Great Pyramid in Egypt. Unfortunately, construction stopped over 800 years ago with the death of the King. A 19th century earthquake cracked it down the middle. We actually climbed to the top of this 500 foot high pile of bricks in our bare feet, with the temperature above 100 degrees. We were not allowed to wear any covering on our feet because this is a religious place and "footwearing" is forbidden in all religious places. It took a week for our feet to recover from the burns.

We boarded a large ferry for a trip down the Irrawady river from Mandalay to Bagan, site of the ancient capital of the country. At stops along the way, the boat stopped and people got off over a rickety wooden plank. Notice the two people (at the right and top middle) standing in the polluted river, trying to sell food to the departing passengers.

This kind farmer showed the children how his ox rotated the mill containing peanuts to produce peanut oil (which dripped into the bowls near the center). The farmer's combined workshop and home is behind the children and shown from the inside in the next photo.

This photo was taken from the "front door" of the home and hearth of the farmer and his wife. It's a simple shack made of bamboo on a sand floor.

Burma is a Buddhist country with thousands of temples, shrines, and pagodas. The most important of these is the Golden Pagoda in Yangon which is series of towers and buildings coated in real gold leaf worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Contrast this photo to the one above and consider whether resources are being properly allocated.

We have seen thousands of Buddha images in various forms. The praying man is being watched over by a smiling reclining Buddha and three Buddhas in the lotus position (all clothed in gold leaf).

Every boy becomes a monk for a short period at a young age; only a few stay on permanently. Every morning at dawn, monks of all ages walk through the village with big black bowls (which they're holding in their laps below) to receive handouts of food for their daily meals. They return to the monastery and from noon until the next morning, they are not allowed to eat. Ari is trying to decide whether to join their ranks.

One thousand years ago, there were three great empires in Southeast Asia -- Burma, Siam (now Thailand), and Kampuchea (now Cambodia). The capital of Kampuchea was Angkor, which we visited at the end of July. The capital of Siam was Sukhothai, which we visited in September. Here we are in Bagan, which was the ancient capital of Burma. From our perch high up on one temple, we could see hundreds of temples and pagodas (there are over 2,000 in all) shining bright orange with the morning sunrise. The river is in the background, just in front of the mist-covered hills.

During our second day in Bagan, while walking through one of the temples, we were approached by a woman named Aye-Aye (behind Ari in the picture below). After a few minutes of limited conversation, she asked us if we would like to experience a real Burmese meal in a real Burmese home. "You should join me and my family for dinner," she continued. Susan and Lee were slightly hesitant, but we agreed and asked her for her address. "Never mind," she said. "I'll send a horse and buggy to pick you up from your hotel at 7:00 tonight." At the appointed hour, she was waiting in front of our hotel with two buggies and drivers and two other friends. We jumped onto the buggies and the horses took off into the night. Within five minutes, we pulled off the main road and started riding down a small dirt road in pitch black darkness. Both Susan and Lee (on separate buggies) began to wonder whether we were crazy to be doing what we were doing, going with unknown people to an unknown location without anyone aware of our plans. Were we being kidnapped or readied for a kill? (The children were totally unaware of our anxiety.) After another ten minutes of bouncing in the dark, we finally came to a tiny village of shacks, and the horses came to a stop. Off we jumped and into Aye Aye's shack we went. Incredibly, there on a small table in this modest abode was a veritable feast with bowls containing meat and vegetable curries, fried eggs, Indian-style breads, rice, and green tea. But around the table, there were only five place settings. The dinner was for us and us alone, while Aye-Aye's friends and family just watched us eat. It was the best Burmese food that we had during our three weeks in the country. Susan begged Aye-Aye and her friends to eat with us, but she said she was content to smell the aromas. Immediately it was clear that Aye-Aye had spent a huge amount of money to prepare this feast in the hope that we would give her a nice "present" in return (and they would eat only what we left behind). She never asked us for anything, but she did tell us that she was a widow raising three children in a rented shack because she couldn't afford the $200 needed to put together her own. Worse of all, the owners of the shack were evicting her at the end of the month and she had nowhere to go.We'll never know which parts of her heartbreaking story were really true, but we were generous with our "present" to Aye-Aye for giving us an unforgettable experience. At the end of the evening, we were driven back to our hotel where we took the picture below. The buggy driver is on the right wearing a traditional longyi, with a soccer T-shirt. Aye-Aye's friend on the far left is wearing traditional Burmese makeup on her cheeks.

That's all for now. On November 10, we leave Bangkok for the last time to travel to Vietnam, India, and from there, we know not where. Our internet access is unknown. Hopefully we will be able to update this site within a month's time.