|

June 6, 2001 Features The Scholarly Effort Senior theses are wide-ranging and all-consuming, and often lead to more questions by Kathryn Federici Greenwood Each year Princeton's senior class sweats through the making of a thesis. Students spend hours poring over books and periodicals, conducting interviews, collecting data, and trying to put into words what they have found. Some seniors push themselves to their creative limits, producing novels, collections of poetry, dances, plays, works of art. The topics covered this year are as varied as the students themselves: black holes, purgatory in medieval art, infant mortality in Mexico, and voodoo in America, to name just a few. The five students profiled here became consumed by their subjects. Although it would be nice to come to some clever conclusions and feel as if they have mastered their topics, these seniors don't claim to do anything of the sort. Their research has often left them with more questions - such is the scholarly effort.

Hillary Freudenthal investigates Philadelphia's inadequate defense system Hillary Freudenthal '01 spent two days a week in Philadelphia, looking through court records and interviewing attorneys. Hillary Freudenthal has learned the difference between having a legal right to public documents and being able to actually put her hands on them. "It's been incredibly difficult to get data to work with and to figure out first what I needed and what's available . . . and then how to get through the bureaucracy," says Freudenthal, a sociology major from Wyoming who studied Philadelphia's mediocre indigent capital defense system. In Philadelphia, poor people accused of capital crimes are randomly assigned either to a court-appointed (private) lawyer or to the Defender Association, similar to the public defender's office in other cities. Since 1993, when the Defender Association started taking on such cases, none of its clients have received the death penalty compared with over 60 of those assigned to private lawyers. Freudenthal set out to explain that discrepancy by looking at, among other things, the fees paid to the two groups of lawyers, the financial resources available to them for investigation expenses, and the lawyers' qualifications. "I spend two days a week in Philadelphia, looking through court records and/or interviewing attorneys. The other three days a week, I spend the mornings on the phone trying to track down information," Freudenthal said in February. Finding a valid sample of homicide cases proved difficult because of labyrinthine record-keeping by the Philadelphia Court Administration. So she had to create her own database. Next she tracked down the court files for the cases - no easy task, and they turned out to be incomplete. It took five months to acquire records of the payments to attorneys for each case in her sample. Despite Philadelphia's disorganized and unaccommodating record-keeping system, she was able to gather enough data to come to some conclusions. The information she collected suggests that the private lawyers' pay is insufficient (on average $3,000 per case), they receive minimal training, and they have a hard time securing money from the courts to pay for investigators and experts that would help their clients' cases. Add to the problem a DA's office that aggressively seeks the death penalty, and their clients are prone to receiving that sentence. The Defender Association attorneys are salaried and have much more time and many more resources to properly prepare for their cases. Come April 20, Freudenthal handed in her thesis without completely finishing her study, due to the difficulty of acquiring documents. But she continued to push for information well past the thesis due date. "This thesis will be big news when it's finished," said Freudenthal's adviser, Bruce Western, a professor of sociology. "At least one prominent criminologist who has done death penalty research (Jeff Fagan at Columbia) is very interested" in her data. "I don't think this research in itself is going to change the world or the world in Philadelphia," says Freudenthal, who wants to volunteer for Africa's AIDS relief effort next year and then attend law school. "But what I hope is that it will give them indications of what parts of the indigent defense system they need to look at again."

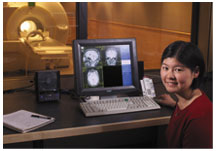

Amy Wong studies the brain and perception Amy Wong '01 in the neuroimaging facility in the basement of Green Hall. We've all probably seen the Necker cube, a line drawing of a transparent, three-dimensional cube. When we look at it, we perceive it in one of two ways: as if we are looking down at it or as if we are looking up at it. "This is intriguing because the picture of the image itself is not changing," says psychology major Amy Wong from Palo Alto, California. "But the brain automatically switches from seeing the figure one way (percept) to the other." Wong spent her senior year trying to figure out whether we have control over how we perceive the cube, what is occurring in our brain to cause the percepts to flip back and forth, and what parts of the brain are at work. To do that, Wong conducted a behavioral study and then took brain images and measured blood flow in six volunteers using a multimillion-dollar functional magnetic-resonance-imaging (fMRI) scanner located in the basement of Green Hall. While inside the scanner, each volunteer looked at the cube on a computer screen and performed one of three tasks at a time. For the "passive" command, they reported which percept (top-down or bottom-up) they saw by pushing buttons on a small keyboard they held in one hand; for "active" they tried to induce a percept switch; and for "stay" they tried to prevent the switch from occurring. "Ambiguous figures [also called reversible figures, of which the Necker cube is one] have always intrigued me," says Wong, who will attend medical school next fall. "I remember the first time I was introduced to these figures, trying to switch percepts, and really being able to feel my brain at work - almost giving me a headache." Wong has found that people can control their perceptions to a limited extent - our effort to sustain a desired percept eventually fails - and she identified areas of the brain involved in attempts to control perception. Her results suggest that "our ability to control what we perceive . . . uses higher-level brain regions [which are involved in more complex activities] that impose top-down influence. So although the image on the retina remained the same, our brains can draw upon our knowledge of the two forms of the Necker cube to partially control what we perceive. "There are so many things in the world that we see on a daily basis," says Wong. "And our brain automatically interprets what these things are so they make sense to us." Ambiguous figures "challenge the brain at this task."

Todd Johnson probes death row conversions "There is so much religious life within death row inmates," says Todd Johnson '01, who wrote to prisoners he found through the Internet. Todd Johnson has received a lot of mail this year, from men living in Texas, Louisiana, Alabama, and Ohio. They aren't his high school buddies. They are inmates convicted of murder. "This is my thesis right here," says Johnson, pulling out a stack of white envelopes. A religion major and premed student from Florence, Alabama, Johnson studied the spiritual journeys of inmates condemned to death. He's interested in how death row "causes people to consider questions [about God, evil, justice, forgiveness] in a different light." Because such prisoners can count the number of years or days they have left, "the questions are so much louder," says Johnson, who attended a conservative Christian high school. With few secondary sources, Johnson conducted much of his own research by writing to inmates he found through the Internet, asking them how death row has shaped their faith, and analyzing the responses he received from 30 men. He heard from Christians, Buddhists, Muslims, and atheists. For some inmates, time on death row saves them from themselves and the evil they were committing on the streets. They view their incarceration as an act of God's will and an opportunity to grow closer to God or, for atheists, a chance to find the "Truth." For Brett Harfmann, on death row in Ohio, religion offers hope. In a letter dated November 16, 2000, he wrote to Johnson, "I know [God] allows things to happen for a reason. I may not fully understand his reason for this, but I'm sure it will be clear one day. . . . I am innocent of the crime I am here for, but I was leading a life style of drugs and alcohol that if I had not ended up in here and gotten away from all that I would have ended up dead or in here for something I did do." But other inmates in his study haven't found solace in faith. They are angry with their predicament, claiming innocence and wondering how God could do this to them. Some prisoners have turned away from religion and God altogether. Johnson came to no grand generalizations regarding people's experience of God on death row - why some grow more spiritual while others turn away from religion. But he noticed several conditions that become catalysts for religious conversion: the knowledge of the exact date of execution, the finite amount of time left to inmates, the institutionalization of pain in prison, and the search for forgiveness. He steered away from tying everything up in a neat package. "I don't want to give the impression that [spiritual life on death row] can even be put into words. . . . I'd like to leave some of it as being ineffable." Working on this thesis hasn't been a chore, says Johnson: "There is so much religious life within death row inmates. It's really been edifying for me personally." The hardest part, he says, has been "the emotional involvement." The men he corresponded with told him about their fears, their families (many of whom have abandoned them), their hardships. Some asked for financial help. Most were happy just to receive a piece of mail. All are marking time. Rolando Ruiz, on death row in Texas, wrote, "Here lately, I've had a lot of questions. The one I repeatedly ask myself is . . . Can I ever be forgiven?"

Patrick Zahn tackles the rising tides Patrick Zahn '01 explored the pros and cons of installing mobile floodgates to hold back high tides at each of three inlets to the lagoon surrounding Venice. As a civil and environmental engineering student, Patrick Zahn is accustomed to finding clear-cut answers to problems. But he hasn't come up with one to his senior thesis. He tackled the centuries-old flooding problem of Venice, a remedy for which scientists, engineers, and politicians cannot agree on. So far, Italy has been addressing the sinking by building up the walkways every couple hundred years or so. But with Venice's architecture and livelihood at stake and high tides becoming more frequent, more needs to be done. The solution on the table, proposed by the Consorzio Venezia Nuova (CVN), an Italian agency comprising public and private civil engineering firms, is mobile floodgates. The floodgates are controversial, and their erection has been stalled by a group of archaeologists and geologists at Colgate University who have introduced new data. Zahn explored the pros and cons of the floodgate solution and looked for any consensus among the parties involved. CVN and an independent research team from MIT that oversaw the environmental impact assessment of the mobile-floodgate solution both claim that the ground beneath Venice is sinking about four centimeters per century and that the sea will rise anywhere between zero and 49 centimeters, if global warming is taken into account. CVN only factors in global warming's effects on sea level in its high-end scenario. Under CVN's proposal, floodgates, lined up next to each other, would be built at each of the three inlets of the lagoon surrounding Venice. They would be raised by air pumps only when water rises one meter, and they would hold back a tide-level rise of up to two meters. CVN predicts that the gates would close off the lagoon about seven times a year for an average of four and one half hours per closure. Under those conditions "the ecology of the lagoon is not really affected," says Zahn, of Riverside, California, who plans on eventually applying to graduate school to study climate change or meteorology. The gates are only a temporary solution - by the middle of this century they might be closed 70 times per year due to rising sea levels. The group of scientists from Colgate believe that the data the CVN and MIT scientists used to predict sinking rates and rising sea levels are inaccurate. Factoring in global warming as a baseline rather than a high-end scenario, the Colgate scientists predict Venice will sink at a much faster rate relative to sea level, at least 30 centimeters over the next century. This will lead to more frequent floodgate closures and adversely affect the lagoon's ecology. "It's surprising that they just can't sit down and say 'Let me see your numbers. They're different from mine. What should we do?' " says Zahn, who has interviewed people from the CVN, MIT, and Colgate camps. As it is, the two sides criticize each other's methods in journal articles. When pressed for his remedy to the situation, Zahn sighs, "The problem is there are so many things we don't know that we could know better" - the effect of global warming on sea levels, how many gate closures would be necessary, and how that would affect water quality and port traffic. "It's a mess." Perhaps, he says, Italy could install the gates but not use them until further studies are conducted. His senior thesis has taught Zahn not only about Venice, but also about tackling a wily engineering and environmental problem, which is sort of like a philosophy class he once took: "It wasn't for me. I mean, there are no answers. I'm always looking for answers. And there are limits to that - is what I'm recognizing."

Ryann Manning traces AIDS in South Africa Ryann Manning '01 twice traveled to South Africa to interview political players in the AIDS crisis. "I don't think you can spend any time at all looking at the AIDS epidemic in South Africa without becoming emotionally involved. You can't read about this many people dying without feeling like you want to do something to stop it," says Woodrow Wilson School major Ryann Manning from Marlborough, New Hampshire. For almost a year, Manning has immersed herself in the AIDS crisis in South Africa, reading anything she can on it, traveling to the country to conduct interviews, and staying up to all hours of the night in her carrel in the basement of Robertson Hall trying to figure out what has gone wrong with the South African government's response to the disease. A Woodrow Wilson task force on South Africa's economic development, taught in her junior year, turned Manning on to the country and its problems. "I realized it was somewhat artificial to talk about anything else in terms of development when AIDS threatens to kill - in estimates released by UNAIDS in July - half of all current 15-year-olds in South Africa," says Manning. South Africa has one of the fastest-growing epidemics in the world. In her 125-page thesis, she traces the government's response to the disease, starting around 1990. The major culprit in the mismanaged AIDS crisis, says Manning, has been politics: the transition from apartheid to a new and inexperienced democracy, key government officials unaccustomed to developing and implementing a national policy, few capable officials at the provincial level, and lack of effective leadership from Nelson Mandela and his successor, Thabo Mbeki. Her recommendations to South Africa's government: Stop reacting defensively to policy criticism, make implementation the highest priority, incorporate NGOs into the national plan, and improve the monitoring and evaluation of programming. But, she says, "Who am I to say what the South African government should do?" Visiting the country and meeting the people proved particularly valuable to her research. "It's difficult to write with any legitimacy about a place you have never seen. I didn't really understand South Africa - not that I do now, but I didn't understand it at all until I was there." Manning isn't turning

her back on her thesis topic. She was awarded a one-year Labouisse

Fellowship and in August will return to South Africa to study and

conduct research on AIDS at the University of Natal in Durban, as

well as work with community organizations. "I couldn't bind

my thesis and hand it in and walk away from this issue at this point."

Kathryn Federici Greenwood is PAW's staff writer.

|

||

Defending

the poor

Defending

the poor Mind

control

Mind

control Letters

from prison

Letters

from prison Death

of Venice

Death

of Venice A

population decimated

A

population decimated