March 13, 2002: Class Notes

Class Notes Profiles:

Civil

rights under siege

Anthony Romero 87 heads ACLU at a critical time

Apprentice

to dead geniuses

Daniel Castor 88 draws architectural treasures

Activist

for AIDs sufferers

Amy Kapczynski 96 helped make drugs more accessible in South Africa

Email your class notes...many secretaries have email. Check our online Class Secretaries Directory.

Anthony

Romero ’87 heads ACLU at a critical time

Anthony

Romero ’87 heads ACLU at a critical time

So much for easing into a new job. Anthony Romero ’87 had been executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union for less than a month when terrorists attacked New York and Washington, D.C. Suddenly, issues like government wiretapping authority, racial profiling, and the detention of immigrants moved from the realm of the abstract to the subject of a very real national debate. And the ACLU is taking its usual strong (some say extreme) stands in defense of the Constitution.

Romero says the crisis has brought the 81-year-old organization back to its roots. “We’ve been sounding the note that the U.S. must stay safe and free,” he says. “Right now young people will grow up in a new climate of civil liberties and civil rights that is being defined at this moment.”

Reaching out to teens and twentysomethings was one of Romero’s goals when he was appointed to lead the ACLU in May. “It’s always hard to reach the younger generation that didn’t live through the civil rights movement,” says Romero, who earned a law degree from Stanford. It helps that, at 36, he’s just a few years removed from them. He grew up in the Bronx, and as a high school senior received an invitation to visit Princeton through a minority recruitment program. He went, and was so taken with the school that he canceled visits to other colleges. “I loved the focus on undergraduate teaching, and my interests were always in international affairs and human rights,” says Romero, who majored in the Woodrow Wilson School and wrote his thesis on immigration to the U.S. by Latin Americans — a topic near to his heart because his parents came to New York from Puerto Rico.

The ACLU lured him away from the Ford Foundation, where he had been

director of human rights and international cooperation. Romero’s

immediate goals: making sure attempts to catch terrorists don’t lead

to a further clampdown on civil liberties, and boosting the group’s

300,000-strong membership. Internet applications, he says, are already

on the rise. By Katherine Hobson ’94 ![]()

Katherine Hobson is an associate editor for U.S. News & World Report.

Daniel

Castor ’88 draws architectural treasures

Daniel

Castor ’88 draws architectural treasures

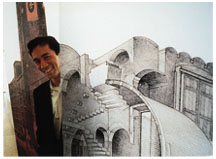

Caption: Castor poses next to a large-scale reproduction of his drawing of Berlage’s Amsterdam Exchange.

Daniel Castor ’88 knew in high school that he wanted to be an architect, and once that decision was made, there was no looking back. His pursuit of the profession has been full of serendipitous turns and a remarkable intensity of purpose that led to the development of an innovative way of drawing buildings. The most recent twist has taken him to where he feels, in some ways, he should have been all along: designing buildings.

Last year Castor established an architecture firm based in San Francisco, Castor Henig Architecture, with a friend from his days at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. “It’s been a bit like starting from scratch all over again,” he says. To date, the firm has worked primarily on residential additions and renovations. “You could say that almost 15 years after leaving Princeton, Danny Castor has finally figured out what he’s supposed to be doing,” he jokes.

You could say that, but if he hadn’t taken the time to figure it out, he wouldn’t have developed his detailed, intricate, and lovely style of drawing buildings, which he spent years laboring over and perfecting.

He calls his works “jellyfish drawings” because of their ability to depict the details of a building’s inside and outside at the same time, which “transform hard walls into looking glasses of architectural revelation,” according to the Los Angeles Times.

Castor began working on this type of drawing in 1992, when he received a Fulbright followed by a grant from a Dutch organization to draw the Amsterdam Exchange, a masterwork designed by Dutch architect H. P. Berlage. “I wanted to draw so much,” he says. “The goal for me was to make a single master drawing, where people could instantly understand a building’s outside and inside simultaneously.”

He spent three years working on 22 drawings of the Amsterdam Stock Exchange, a body of work that was exhibited in Rotterdam, and then at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles and published in Drawing Berlage’s Exchange (1999), for which he received a Citation for Excellence from the American Institute of Architects.

After going back to Harvard to finish his master’s in architecture, Castor spent a year at the American Academy in Rome, where he started on a new series of drawings beginning with Bramante’s Tempietto. But he wasn’t earning a living and he realized that, despite his love of drawing, he wanted to design buildings that people would actually live in.

He likens the years he spent drawing to “apprenticing with dead

geniuses.” It’s a very different type of endeavor than working

with live clients, but many of the same lessons apply. “The buildings

I drew are all icons. I learned so much by trying to find ways to represent

their very powerful experiential qualities,” he says. Although he

hopes to eventually combine design and drawing, for now he’s concentrating

on establishing his firm. “For someone who’s been kind of living

in the ether for so long, [designing buildings] has been tremendous fun,”

he says. ![]()

By Andrea Gollin ’88

Andrea Gollin is a Miami-based writer and editor.

Amy

Kapczynski ’96 helped make drugs more accessible in South Africa

Amy

Kapczynski ’96 helped make drugs more accessible in South Africa

When Amy Kapczynski ’96 began her first year at Yale law school last year, course work wasn’t what consumed her. Instead, the memory of 5,000 demonstrators demanding medication at the July 2000 World AIDS conference in Durban, South Africa, drove her to forsake sleep and leisure in pursuit of affordable HIV treatment for all.

Working with Doctors Without Borders, Kapczynski researched the licensing agreement between Yale and Bristol-Myers Squibb, which holds the patent on d4T — a crucial drug in HIV treatment that was invented by Yale professor William Prusoff and is too expensive for impoverished populations. Her findings helped Doctors Without Borders argue that the public interest was not being served as outlined in the agreement. She then mobilized sympathetic students and faculty — chief among them Prusoff — alerted media to the story, and watched the campaign snowball. The pressure she and her allies exerted led to an unprecedented announcement last spring: Bristol-Myers Squibb would not enforce its patent on d4T in South Africa. As a result, South Africa could import or produce generic versions of the drug.

Surprised at the swift success, a modest Kapczynski was jolted, too, by the “insane glorification of me” that occurred afterward. She insists that the activists before her who put universal treatment of AIDS on the domestic agenda are the ones to be applauded.

The New Haven, Connecticut, resident first confronted the AIDS pandemic in Kenya, where she taught high school students through a summer program after her sophomore year at Princeton. Following her studies at Cambridge University as a Marshall Fellow, she then worked for a British AIDS organization.

Though encouraged by the latest victory, Kapczynski intends to monitor

negotiations between Yale and Bristol-Myers Squibb, which still holds

the patent, and South Africa’s Aspen Pharmacare, which wants to make

affordable d4T. “It’s a common strategy to make big promises

in the press and work out the details in a closed room, months down the

line, when no one is paying attention,” she says. “I’m

cynical enough to believe there is still work to be done.”

![]()

By Regina Diverio

Freelance writer Regina Diverio is the former editor of Drew magazine.