March 13, 2002: Features

Beyond the call

Armed with the skills to heal the sick, alumni physicians help the underserved and disabled

By Kathryn Federici Greenwood

The job of a doctor is a demanding one, today perhaps more than ever as pressure mounts to squeeze in as many patients as the day allows. Nonetheless, the desire

to help and to heal — the impulse that often motivates people to go into medicine in the first place — continues to inspire a number of doctors to do even more than their practice requires. The following three Princetonians are just a few of the physicians who go beyond the call of duty in their professional lives.

Theresa

H. Liao ’92

Theresa

H. Liao ’92

Fighting the system

Caption: Theresa Liao ’92 consults with a patient in her office in a New Haven clinic. (photo by Ricardo Barros)

For a doctor in a federally subsidized community health clinic, practicing medicine is not as easy as making a diagnosis and filling out a prescription. For every 15 minutes internist Theresa Liao ’92 spends with a patient at the Fair Haven Community Health Center taking a history, performing a physical exam, and discussing his condition, she estimates she spends “another 15 minutes maybe making a special sheet for the patient where you tape down the pills and make some symbols next to it so they can understand because they can’t read.”

Thirty-five percent of the clinic’s patients have no insurance or are underinsured. Many of them are undocumented Latinos, and some are homeless. Many of Liao’s patients can’t afford to pay for medications and diagnostic tests, or come up with bus fare to travel to a specialist. Even discussing test results can be difficult, because some patients have no phone.

So Liao and her colleagues help the New Haven, Connecticut, residents fill out forms to receive free drugs, and with social workers arrange transportation to other offices for consultations with specialists. The wait for free drugs can take up to six months. In the meantime, Liao makes do with the appropriate free samples from the clinic’s supply room. But “that’s totally confusing to the patient to be switching medications,” says Liao.

As for lab work and tests, sometimes she can’t even order what she believes is critical. “In some ways you have to be a better clinician. If you don’t have access to all these high-tech diagnostic tests where you can get your answer back quickly, you have to get the history better, do a better physical exam. It’s a little bit more like Third World medicine.”

For Liao’s patients, just getting to the clinic is a challenge. “You have people who are working three jobs. They are supporting their entire family, and they barely have time to come see you because they can’t possibly take off,” she says. They “have to make a choice between buying food or buying medication. It’s something that day to day we see.” She even sees patients who should be hospitalized but refuse to go because they know they can’t afford the bills. And then there are the specialists who tell her, “Please don’t send your uninsured patients to me.”

Helping the indigent population navigate the public health system can be emotionally draining. “The system is designed to thwart us at every turn,” says Liao, who speaks Spanish, Taiwanese, and Mandarin.

Still, she loves her work. “I’ve been so lucky to fall into this job. I’m doing what I really want to do,” says Liao, an East Asian studies major whose parents emigrated from Taiwan to the U.S. “As a human being this is my responsibility. This is something that I should do, that I want to do, and I’m happy doing it.” In college, she thought hard about “what would be the most useful thing to be” and determined that it was a primary care doctor. “So many people are in need of basic health care. So many people are suffering needlessly, and if I can do small things to help them, then I’ll be very happy.”

Liao, who earned her M.D. from the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey (UMDNJ) in Newark, then completed a three-year residency at New York University Hospital, estimates she earns about three-quarters of what a starting internist in a private practice in New Haven would make. She’s on salary and can’t expect any increase besides cost of living. “Some people might look at me and say, ‘You’re not getting paid nearly what you could be getting paid.’ But I make more money than 99.9 percent of the world. I’m comfortable. I don’t need three cars.” In fact, she feels guilty every time she rolls into the clinic parking lot in her new Subaru Forester. Still, “There’s nothing I’d rather be doing than working here,” she says.

Bill

Greene ’68

Bill

Greene ’68

Bringing healing, finding peace

Caption: Bill Greene ’68, fifth from left, has twice traveled to Haiti to provide medical services to the impoverished people there and finds the journey spiritually satisfying as well as helpful.

William R. Greene ’68 knew there was something else he was supposed to be doing with his life. A urologist in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, he “became increasingly aware of a sense of frustration, a lack of fulfillment in my daily routines.” A committed Catholic, he prayed about it frequently, and found his call in the people of Haiti after learning about a colleague’s volunteer work there.

His wife and daughter were understandably apprehensive about his going to Haiti to treat the sick, many of whom are HIV positive. Political corruption is the rule in Haiti. With no stable industry, people are poor and desperate. “Haiti is a very dangerous place,” says Greene, who has made two week-long trips, in August 2000 to H¯opital Lumière in Bonne Fin with three U.S. colleagues and in November 2001 to H¯opital Albert Schweitzer in Deschapelles by himself.

Greene calls the trip to H¯opital Lumière “the most miserable journey I have ever made.” He witnessed “almost indescribable poverty: People lived in shanties with slabs of tin as roofs and plywood or branches for walls, garbage covered the island.”

Patients walked for miles to be seen by the visiting U.S. surgeons. The temperature in the operating room “started at 90 degrees” and went up during the day, says Greene. “Instead of instruments arranged on shelves in cabinets, there was a central mound two feet high and four feet wide. We would rummage through the inventory to find what we would need for each case. The hospital pharmacy was limited and disorganized. Postoperative analgesics were almost nonexistent.” Despite the primitive conditions and the serious illnesses of many of the people, during his two missions to Haiti Greene performed 52 surgical operations without losing a patient.

Many patients don’t see a doctor in Haiti until they are at the end stage of a disease, says Greene, who was accepted into Upstate Medical Center in Syracuse after his third year at Princeton. Some people go first to voodoo priests, who are “charlatans with nothing to offer.” Because of this neglect, Greene treated people with conditions that he has never seen in the U.S. — malaria is epidemic, and tuberculosis and tetanus are common. One man for years had carried around 10 pounds of fluid in his scrotum (a hydrocele), due either to an infection or an injury.

Greene’s journeys to Haiti are as spiritual as they are medical. Struck as he was with the poverty of Haiti, Greene was also impressed with the inner strength and depth of the faith of its people, 90 percent of whom are Catholic.

After his first trip, he says, “I left totally drained — but what a marvelous feeling of satisfaction and inner peace. I will never forget the kiss I received from the woman with urinary incontinence, or the smile on the boy with the bowlegs now straight.”

His experience in Haiti has changed his life. “There’s so much in the U.S. that we just don’t appreciate,” says Greene, who has raised $50,000 in cash and about $20,000 in medical supplies for the Haitian people. “I can’t sit down to any meal and not think about the people in Haiti, 60 percent of whom go to bed hungry every night.”

He’s already planning his next trip. “I feel like I’m on a journey and I’m not sure where I’ll end up,” says Greene. Serving the poor in Haiti “might end up being my life’s work.”

Jenfu

Cheng ’93

Jenfu

Cheng ’93

Helping kids scale mountains

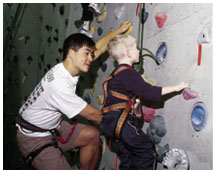

Caption: JenFu Cheng ’93 helps Patrick Garvey up the climbing wall. (photo by Dan Katz)

On a Tuesday evening in mid-December, Joanne Garvey drove her twin boys, John and Patrick, an hour to an indoor rock-climbing gym in Fairfield, New Jersey. This wasn’t just another extracurricular activity for the skinny, blond, six-year-old brothers. John, who suffers from cerebral palsy, can’t walk. Patrick, who is afraid of heights, has been diagnosed with developmental delay and attention-deficit disorder. But by night’s end, both boys had made it to the top of the wall, thanks to a handful of volunteers organized by JenFu Cheng ’93, a resident in physical medicine and rehabilitation at UMDNJ. A year and a half ago, Cheng founded Peak Potential, a nonprofit program that provides children with physical disabilities with the opportunity to rock-climb.

The activity disguises therapy as play. “These kids need therapy for their entire lives,” says Cheng. “Standard therapy can get tedious,” but making it fun “will keep their interest and optimize their enthusiasm.”

Most of the children who participate in Peak Potential have cerebral palsy, which affects their muscle strength and coordination. The children wear full body harnesses attached to a rope anchored at the top of the wall and controlled by a volunteer on the ground who can help support the child’s weight. Early on during the December 18th session, Patrick started crying halfway up, so Cheng quickly scaled the wall to lend emotional and technical support. A psychology major at Princeton who earned his second bachelor’s degree, in biology, at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and his M.D. from UMDNJ, Cheng is good with the kids. He makes them laugh and feel comfortable. “I think I’m just a climber who happens to be a doctor sometimes,” he tells John and Patrick.

Rock-climbing not only develops strength and coordination, but it also builds self-esteem, confidence, and trust, says Cheng, who has been rock-climbing since he first scaled the wall in Princeton’s Armory his junior year. Patrick’s mom, who was busy taking photos and encouraging her sons — “Get your feet on, let’s go!” — says, “John can’t do a lot of things,” but he’s proud that he can rock-climb.

Parents and their kids, ranging in age from 3 to 15, travel from as far away as upstate New York to attend free sessions at Rock Gym, which donates the time. Cheng runs two to three 90-minute sessions per week, but those aren’t keeping up with the demand. About 30 kids participate now, and Cheng, who along with his relatives put up money early on to get the program going, has had to start a waiting list because he doesn’t have the money to provide more sessions.

The volunteers, some of whom are doctors, offer lots of encouragement to the kids, whether they get all the way to the top or just partway.

Cheng has been especially impressed with a seven-year-old girl with spinal muscular atrophy. When she started with the program about a year ago she was still able to walk, but she has become weaker at each session. Even so, “she’s trying and fighting on the wall as hard as she did the previous time even though she requires more assistance. It doesn’t seem to faze her,” says Cheng, who lives in West Orange and grew up in Roseland, New Jersey.

“I love kids in general but these kids in particular because they

are especially inspiring to me,” says Cheng, who plans on subspecializing

in pediatric rehabilitation. “For these kids who have these special

needs, it’s even a challenge to play. But when you provide them with

an opportunity to do that, that’s all they want to do.” ![]()

Kathryn Federici Greenwood is PAW’s staff writer.

PAW Online: For photos and an essay by Bill Greene ’68 describing his first trip to Haiti, go directly to PawPlus at www.princeton.edu/paw/plus.

For more information:

Dr. Theresa Liao: liaotheresa@hotmail.com

Dr. William Greene: gudoc96@hotmail.com

Dr. JenFu Cheng: www.peakpotentialclimbing.org