October 9, 2002: Features

Whitman

College architect Demetri Porphyrios *80 sees contemporary significance

in traditional themes

Whitman

College architect Demetri Porphyrios *80 sees contemporary significance

in traditional themes

By Catesby Leigh ’79

Corinthian columns, a feature of much classical architecture, rise four stories in Three Brindleyplace, an office building in Birmingham, England (1995), designed by Demetri Porphyrios *80 (inset).

The office building on London’s Great Portland Street where Demetri Porphyrios ’80 has his architectural practice is a century-old classical edifice whose nicely detailed stone façade is aging gracefully. The Porphyrios Associates office, in contrast, is starkly modern, with walls and partitions painted bright white.

Perhaps the contrast is deliberate, because Porphyrios does not want to be taken for an antiquarian. Nevertheless, his firm is one of the five leading classical architectural practices in Britain, and Porphyrios assigns great value to cultural continuity in architecture and urbanism. Having won major commissions at Oxford and Cambridge during the 1990s, he will now bring his rigorously formulated architectural philosophy to the design of a collegiate-gothic Whitman College, which will house 500 students — mainly from the four undergraduate classes but also some graduate students — when it opens on a site between Baker Rink and Dillon Gymnasium four years from now.

Whitman College will be the first new collegiate-gothic building at Princeton in more than half a century. “The shrinking mass of the historic campus relative to the university as a whole became a matter of great concern, because it’s there that many alumni have their happiest memories of the Princeton campus,” says architect and well-known urban planner Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk ’72, who chairs the trustees’ Committee on Grounds and Buildings. As a result, “there’s been more discussion of style as it bears on the image of the campus. And with the concern that the university’s identity was perhaps disappearing came the realization that it could be reinforced.”

|

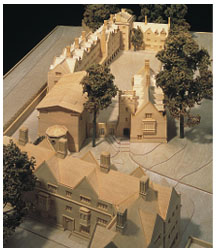

The Battery Park City Pavilion in New York (1990) is an example of Porphyrios’s philosophy of design, where the focus is on classical proportion and structure. The Grove Quadrangle at Magdalen College, Oxford (1991), where Porphyrios combined two styles — the classical auditorium on the left and the gothic dormitory on the right — meshes almost seamlessly with the college’s existing gothic buildings

A model of the Grove Quadrangle.

The town of Pitiousa on the eastern end of the Greek island of Spetses was designed by Porphyrios in the 1990s. He was able to bring his instinct for pleasing proportions to the project, which included residential neighborhoods and public spaces.

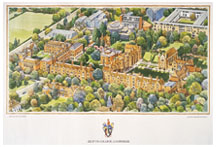

The plan for Selwyn College, Cambridge, comprises residential accommodations, administrative facilities, a library, and an auditorium.

The seven-story atrium of the office building Three Brindleyplace in Birmingham (1995) features soaring Corinthian columns; a skylight allows natural light to pour in. Photos courtesy Porphyrios Associates. Slender columns rise to the roof of this glass-walled museum pavilion in Athens (1996), evoking the Battery Park City Pavilion shown on page 14. |

For the time being, the university is operating on the premise that Princeton’s buildings located in the older parts of campus should remain traditional in style, while those in the modernist precincts that have appeared since the 1960s should continue to push the proverbial envelope. “That immediately places Frank Gehry in the southeast part of the campus,” Plater-Zyberk notes, referring to the science library project assigned to the architect of the widely publicized Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain, and plotted for the south corner of Washington Road and Ivy Lane.

In contrast, “The new Whitman College should make reference to the wider context of the historic Princeton campus and the great humanist tradition of its collegiate architecture,” Porphyrios wrote in a feasibility study his office carried out before Princeton’s trustees entrusted him with the project.

When Porphyrios speaks of “making reference to” Princeton’s historic campus, he means it. Whitman College will be built with traditional load-bearing masonry walls finished in the argillite fieldstone found on dormitories like Pyne, Laughlin, and Lockhart Halls, and its window and door frames and moldings, as with the older gothic buildings at Princeton, will presumably be of limestone.

But Whitman’s articulation could strike a significant contrast with those buildings. Porphyrios’s architecture is traditional, but it is also somewhat severe, and its abstract lines are scarcely modulated by the figurative sculptural accents — the statues, gargoyles, grotesques, relief panels, heraldic shields, and, of course, tigers — that are one of the glories of Princeton’s gothic buildings.

Short in stature, with jet-black hair combed straight back, sartorially refined, bespectacled, cerebral, and very precise in his manner of speaking, Porphyrios, 53, is a somewhat untraditional traditionalist. “I always felt very uncomfortable with the restitution of the past exactly as it was,” he said during an interview in his office last spring, a few days before he presented his feasibility study to the trustees. “Every significant cultural period has actually taken the past and put its own stamp on it, which was the contemporary element. And that’s why, for me, it’s not like we’re bringing something back. I never really felt that I was looking back, because the past for me is now — the ideas we have, the images we have, the aspirations we have.”

It was not always so. Like just about every other architect of his generation, Porphyrios started out as a modernist. Raised in Greece, he came to Princeton in the early 1970s, having completed his undergraduate studies in Athens, with an interest not just in architecture but also in architecture’s relationship to broader cultural trends.

“I was always very much interested in relating formal aspects of architecture to its social and economic aspects,” Porphyrios says. “I was interested in the relationship between form and the history of ideas and social history as well. Princeton was an excellent venue to pursue these issues.” Princeton professors who influenced Porphyrios included two historians of architectural theory, Anthony Vidler and Alan H. Colquhoun; David R. Coffin ’40 *54, a noted authority on Renaissance architecture and landscape design; and Carl E. Schorske, the well-known cultural historian. After earning master of arts and architecture degrees in 1974 and 1975, Porphyrios spent more than half a year in Finland, gathering material for his doctoral dissertation on the modernist architect Alvar Aalto.

Born in 1898, Aalto was the last of the modernist pioneers whose ranks included Frank Lloyd Wright, Mies van der Rohe, and Le Corbusier. He eschewed the International Style’s glass-and-metal boxes, often building irregularly shaped brick buildings, such as his Baker House dormitory at M.I.T. But Aalto, like most architects of his era, had received classical training, and retained a strong interest in classical buildings and the way they shape cities.

It was something of an embarrassment, Porphyrios admits, to have Aalto “asking me about this or that temple in Greece that wasn’t really familiar at all. I had never had any interest in classical architecture before, although I was surrounded by it.”

While working on his dissertation, Porphyrios embarked on a study of classical architecture. A change of design philosophy, and a systematic philosophy of design, resulted from that study. First and foremost, Porphyrios came to appreciate traditional architecture and urbanism’s incalculable value as a source of enduring human meaning in a world undergoing vertiginous technological change. Porphyrios’s artistic views have come a long way since his student days, in other words, but he has retained a broad cultural outlook. His aversion to a modern, utilitarian ethos that regards buildings as commodities and promotes shoddy construction with “off-the-shelf” materials that don’t age, but just fall apart — an ethos, unfortunately, that is shaping more and more of the Western world’s built environment — is shared by England’s Prince Charles. Indeed, Porphyrios is regarded as one of the small number of architects who have significantly influenced the prince’s architectural outlook.

In sum, Porphyrios is a noted theorist as well as a practicing architect. And while some architects have written treatises that proved largely irrelevant to what they built, Porphyrios’s buildings clearly reflect his principles.

For Porphyrios, the key to understanding a given architectural tradition lies in the structural methods in which that tradition originated. In his influential treatise Classical Architecture (1992), Porphyrios notes the ancient Greeks’ development of a standard approach to timber construction in a primitive era in which they were concerned only with the craft of building shelter — an era antedating the emergence of the art of architecture. Over time, formal characteristics of this standard method assumed a symbolic and mythic significance, and the classical orders — the several types of column (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian) and the entablatures they support — represent the ultimate stylistic development of those characteristics, as well as the ultimate refinement of primitive post-and-lintel construction. Classical architecture, which we commonly associate with marble temples, thus commemorates its origins in timber construction. It is also grounded in reverence for craftsmanship, because the tradition would not exist but for the excellence of the carpenters who unknowingly gave birth to the canon.

Poetic allusion to classical architecture’s historic origins and an insistence on sound craftsmanship and good materials — these are the heart and soul of Porphyrios’s philosophy of design. Decoration is not a primary concern, he said during the interview. “My interest is much more with proportions, with tectonic aspects, with composition, with the rational element in architecture.”

This structural focus is the source of the modern quality Porphyrios seeks in his architecture. It explains his Battery Park City Pavilion (1990), located alongside the Hudson River and a short walk from Ground Zero in Manhattan. This eccentric, picturesque structure, situated on a stepped granite platform, evokes classicism’s origins. The shafts of its 12 outer columns, which could pass for telephone poles, are devoid of the gently swelling contour of classical columns. These columns are perched on quarry-faced granite blocks that serve as crude bases. Metal capitals are wrapped around the shafts, which support beams and the rafters beneath a low-pitched roof with long eaves. The rafters taper at their ends to suggest the modillions, or horizontal brackets, of a classical cornice. Inside the pavilion, four stout Doric columns built of exposed brick are perched on the podium’s summit and support thicker beams than do the skinny outer columns. The Doric capitals combine wood and limestone — reflecting the orders’ eventual perfection in masonry rather than timber construction — and there is a metallic necking band beneath them.

Far less eccentric is Porphyrios’s most important work to date, the Grove Quadrangle at Magdalen College at the University of Oxford. Originally designed in 1991, this quad consists of two buildings containing students’ rooms and administrative offices — one range nearly twice as long as the other — and an auditorium. The dorms are gothic, the auditorium classical, and all are built of load-bearing masonry finished in Ketton stone, which is very pale brown. A cloister runs along the longer range, while the shorter residential building leaves an open view to the east, offering a gorgeous vista of a deer park.

These buildings do not strive to distinguish themselves from Magdalen’s historic architecture, which is predominantly gothic. Approaching the quadrangle, the first view is of the gabled end of one of the ranges and its oriel, which includes a row of five narrow, round-headed windows and, beneath them, a painted heraldic insignia of St. Mary Magdalen. To the side and a little behind this range, a low tower with a crenellated parapet serves as the entrance to the quad. An openwork gothic screen extends between this tower and the auditorium, which is entered through a small polygonal pavilion whose roof is capped by a finial and ringed by little anthemia, a classical flat floral motif.

Corbels in the cloister adorned with roses and lilies that are carved and painted are about all the quad offers in the way of sculptural detail. And yet the architect’s sense of amenity and his emphasis on high-quality craftsmanship are both evident. The nicely configured chimneys with their delicate moldings; the half-timbered dormers; the cloisters’ pointed arches, which are crowned by moldings in their own right; the strap-hinged oak doors; the sloping windowsills and deeply set frames that endow rooms with a pleasing sense of mass and stability that modernist curtain-wall construction scarcely permits — all make Grove Quadrangle a very pleasant environment.

On the outside, however, the auditorium is so sparingly articulated that the intended contrast between its classical design and the ranges’ gothic style hardly registers. The auditorium’s exterior boasts a sundial, round windows, and three empty brackets on which the president of the college, Anthony Smith, hopes to place statues of Magdalen worthies, including Oscar Wilde. The little hyphen connecting the polygonal entry pavilion to the building is awkward; a semicircular portico might have made for a seamless transition. Finally, the roofs on the gothic ranges are situated behind low parapets and don’t have the wonderfully picturesque effect of the more steeply pitched and dominant roofs with which many collegiate-gothic buildings — at Oxford, Princeton, and elsewhere — are endowed.

Nevertheless, it is easy to understand why Magdalen’s student union, asked to choose between Porphyrios’s Grove Quadrangle design and a modernist alternative, favored the former by the lopsided margin of 114—2. Smith is delighted with the way the project turned out. “The other college presidents at Oxford are green with envy,” he declared on a tour of the quad. He is also pleased with a brick squash court facility Porphyrios erected on a beautiful site just outside the college walls, near the willows that droop over the River Cherwell. The facility encloses three squash courts, and its three large round-headed windows, which form an enclosed arcade below a second-floor spectators’ gallery, remind Smith of an orangery.

Porphyrios’s design philosophy first emerged two decades ago in an essay entitled “Classicism Is Not a Style,” and since then he’s been much in demand as a teacher. He has held prestigious visiting professorships at the University of Virginia and Yale. In London, he has taught at the Architectural Association, the Royal College of Art, and at the Institute of Architecture — the latter promoted by the Prince of Wales in an ill-fated effort to break the modernist monopoly on British architectural education.

During the 1980s, Porphyrios’s work included a very fine architectural ensemble for a farm in Ascot, England — a residential hall abutting a pond, along with cottages, barns, stables, and a belvedere evocative of the Tuscan countryside. Simply designed and handsomely detailed to reflect the dignity of traditional village architecture, the ensemble is built of brick, timber, and stone. Porphyrios also designed a villa in Athens and row houses in two grand London neighborhoods, Kensington and Holland Park. These classical residences, whose exteriors are finished in white stucco, manifest a subtle and exquisite sense of line and detail, along with the familiar lack of ornamental accents. With the London row houses, such accents are limited to the anthemia with which Porphyrios often crowns his doorway pediments.

During the 1990s, Porphyrios designed a little town, Pitiousa, for the Greek island of Spetses. Building on a vernacular tradition of white stucco buildings in which simplicity is de rigueur, Porphyrios here has made the most of his instinct for pleasing urban spaces and fine architectural proportions and craftsmanship. The architect’s sense of amenity is again evident — in the graceful pergolas, in the terra-cotta tile roofs with their pretty finial-like chimneys, in the rubblework masonry of the garden walls. It is in such informal settings that he seems to get the most mileage out of his innate talent and his principles of design.

Aside from the Grove Quadrangle commission at Oxford, Porphyrios landed a major expansion project for Selwyn College at Cambridge University, involving the construction of new courts with residential accommodations and administrative facilities as well as a library and theater. Construction has not yet begun on this $50-million project.

In 1995, Porphyrios designed an office building in Birmingham, England, which is noteworthy for its dramatic skylit atrium. This generous open space, the glass-enclosed offices and balconies fronting on it, and the glazed roof’s metal structure convey a sense of lightness that derives from the interior’s steel-frame construction and contrasts with the load-bearing masonry façade. The atrium’s articulation — including Corinthian columns rising four stories above the mezzanine, the familiar anthemia, and the classical brackets supporting the roof structure — is masterfully handled. Porphyrios also designed a royal residence in Amman for the late King Hussein of Jordan and Queen Noor ’73, employing a mainly Islamic architectural vocabulary.

Porphyrios has even built a gray-metal, glass-encased pavilion for a modern art gallery in Athens that harks right back to his Battery Park Pavilion, which constitutes a sort of leitmotif in his work. This time, slender exterior columns support beams adorned with nothing more than brass bosses. And last year, Porphyrios won a competition for the design of a new public library for West Palm Beach, Florida. Here again, the pavilion leitmotif occurs both in a plaza and on top of a belvedere. Located on a downtown site overlooking the Intracoastal Waterway and the Atlantic Ocean, the library’s two buildings, finished in yellow-ocher stucco, are arranged alongside classical arcades, and face a public square at oblique angles to one another, with the belvedere in the background aligned with the orthogonal arcades. It is an interesting, complex arrangement that testifies to its architect’s aversion to tidy, rectilinear urban spaces.

Demetri Porphyrios is very concerned with designing buildings that impart both a sense of formal continuity within Western architecture and a sense of modernity. And yet architecture inevitably bears the stamp of its age — it cannot help but do so. While Porphyrios’s focus on architecture’s tectonic aspects has been particularly successful in informal settings such as the English countryside and the Greek islands, such a focus seems too narrow for a high-profile project in an eminently artificial setting such as Princeton’s historic campus. It’s worth remembering that ornamental forms and figurative decoration — festoons and sculptural totems — were present at architecture’s creation, too. In classicism’s case, the ritual significance of such elements was lost long ago, but the evidence of their enduring artistic relevance to traditional design is overwhelming. Guyot Hall would be nothing more than a nice building without the fantastic zoological display protruding from its cornices and portals. Alexander Hall would be an unmitigated disaster without the great sculptural relief on its southern façade. And perhaps most typical of Princeton, a dormitory like Henry Hall would not be the kind of building that so richly rewards close scrutiny were it not for its sculptural enhancement. In Henry’s case, this includes (but is hardly limited to) two relief panels, one showing Washington crossing the Delaware and the other Washington at the Battle of Princeton, beneath a gorgeous pair of oriels and the prowling tigers carved in the half-timbered dormers above. And where putting the stamp of one’s age on buildings is concerned, we should remember that gargoyles and grotesques are a wonderful means of portraying contemporary fashions and foibles.

Cumulatively, such figurative delights make a vital contribution to the creation of a great architectural environment. To put it more crudely, if every traditionally designed building at Oxford were as abstractly treated as the Grove Quadrangle buildings, Oxford wouldn’t be Oxford. Grove is modest in scale, however, and it is handsome, so that minimizes the relevance of such an observation. Considering, however, the immediate impact the $100-million Whitman College project will have on Princeton’s appearance, and its longer-term impact on Princeton’s architectural patronage, it’s obvious that careful consideration should be given to exploiting all the artistic resources the gothic idiom offers.

In any event, there’s little reason to doubt that alumni whose Princeton memories are pinned to the northwest quadrant

of the campus are going to be well satisfied with Demetri

Porphyrios’s Whitman College. Adhering to his architectural philosophy,

Porphyrios will build a good college. Broadening it, he could build a

great one. ![]()

Catesby Leigh ’79, an art and architecture critic in Washington, D.C., surveyed Princeton architecture in PAW’s May 19, 1999 issue.

Editor’s note: The Whitman College plans are available for viewing at Princeton’s Office of Physical Planning.