November

6, 2002: Pespective

November

6, 2002: Pespective

“The

government’s job is to protect me”

How one fall day changed a life

By Harrison J. Goldin ’57

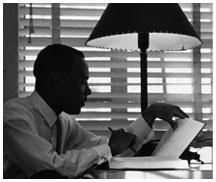

Photo: James Meredith studies in his dorm room at Ole Miss in 1962. (flip schulke/Corbis)

Harrison J. Goldin ’57 was planning a career on Wall Street until his third year in law school, when an instructor told him that Robert Kennedy was assembling a team of trial lawyers to handle civil rights cases in Mississippi. Goldin signed up and, 40 years ago this fall, was working in the Justice Department when he was assigned to be the roommate of James Meredith for two weeks as Meredith became the first black student to attend the University of Mississippi. Here, Goldin — a former New York City comptroller and New York State senator who now runs a corporate restructuring advisory firm in New York — recounts his time with Meredith and its impact on the rest of his life.

On a lovely Sunday afternoon, September 30, 1962, accompanied by U.S. marshals and FBI agents and armed with a federal court order mandating his enrollment, James Meredith, the first black to matriculate at the University of Mississippi since at least Reconstruction, arrived on the Ole Miss campus to register for classes.

Meredith’s presence attracted a crowd, which soon turned into a mob. That night President Kennedy mobilized the National Guard and installed a large federal security presence on the campus to protect Meredith and enforce the order of the federal court. But before order was restored, two people were dead and many wounded.

Before 8 a.m. the following morning, a telephone call summoned me from my first-floor office in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division in Washington to Attorney General Robert Kennedy’s suite on the second floor. It was an anxious moment for a newly minted young lawyer, barely a year out of school. The majestic dimensions of Kennedy’s office were intimidating, and the attorney general was surrounded by a phalanx of young aides. Still, he quickly put me at ease. He outlined the situation: To maintain order at Ole Miss and ensure full implementation of the federal court writ mandating Meredith’s status as a student, the president had determined to maintain an armed presence on the campus for as long as necessary.

With Nicholas Katzenbach ’43, the deputy attorney general, in charge of overseeing all federal forces on the ground at Ole Miss, Robert Kennedy felt it would be useful for a Justice Department official to become Meredith’s dormitory roommate. I was young and single, and Kennedy assumed I could move quickly. Would I be willing to leave immediately for Ole Miss to live with James Meredith and relay his anticipated movements to Katzenbach?

A military helicopter got me to Ole Miss before 5 p.m. I was taken immediately to meet Katzenbach in the field kitchen tent where he was eating dinner.

The campus had a surreal quality: Before the week was out, more than 25,000 troops would be committed to the operation. I quickly settled into a routine with Meredith.

Each morning as we dressed he would outline his schedule: say, breakfast in the campus cafeteria, his first class, a visit to the campus bookstore, a stop at the library, a second class, lunch, etc. I would brief Katzenbach, and he would gather the commanders of the various security forces and plan that day’s protection strategy.

After dinner Meredith and I would sit in the dormitory room while he studied and I read the newspaper. On Wednesday evening, my third day on the campus, Meredith looked up from his books and casually mentioned that the next morning he was planning to pick up tickets for the opening football game that Saturday.

I was stunned: “Oh, Meredith,” I said, addressing him as he preferred, “you can’t do that. The football stadium will be a disaster for you. Thousands of fans will be in a fever pitch; by halftime a lot of them will be drunk. You’ll be the only black face in the whole arena. There’s no way to protect you in an enclosed space like that.”

Meredith dismissed me quietly and firmly: “Look,” he said, “I’m here because a U.S. District Court judge said I have the right to be here and do what every other student does on this campus. Saturday, they’ll all be at the football game, and I will, too. The job of the government is to protect me.”

I found Katzenbach, who came immediately to reason with Meredith. “Look, Mr. Katzenbach,” Meredith said, “I’m at Ole Miss only because a federal court has ruled that I have the right to be here and do on this campus what every other student is doing. Saturday, they’ll all be at the football stadium, and so will I. The job of the government is to protect me.”

Katzenbach remonstrated, but to no avail. Meredith and I went back to our reading. Twenty minutes later the telephone rang. I answered it. “This is Robert Kennedy. Can I speak to Mr. Meredith, please?”

Meredith listened to the attorney general, and I soon heard him say, “Mr. Kennedy, I appreciate your concern. But I’d like to remind you that I’m here only because a U.S. District Court has said I have the right to be here. Under that order, I can do whatever any student on this campus can do. On Saturday they’ll all be at the stadium watching the football game. I’m going to be there, too. The job of the government is to protect me.”

The conversation ended. Less than half an hour later the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was on the phone.

Again, Meredith listened respectfully to his caller, and again provided his usual response, ending, “The government’s job is to protect me.” No more than 10 minutes later, when the phone rang the voice at the other end said, “This is the White House. The president would like to speak to Mr. Meredith.”

I knew the script: “Mr. President,” Meredith said, “I appreciate your concern. I’m here only because a federal judge has said I have the right to be here. On Saturday the other students will all be at the football stadium, and so will I. Your job is to protect me.”

People often have asked me why I spent nearly a quarter-century in elected public service. The events that Wednesday evening in 1962 were an epiphany: For all its failures and shortcomings, what an extraordinary country this is! Where else do a constitution and judicial system allow a single individual to assert his rights so forcefully, confront a president, and invoke the full majesty of a nation to protect him?

The outcome? In a hurried conversation later that

evening (which can be heard at the National Archives) President Kennedy

and Governor Ross Barnett of Mississippi decided that the only solution

was to move the game to another part of the state. The sanctity of the

order of a federal court was preserved. ![]()