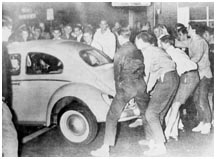

As onlookers watch happily, Princeton undergraduates move a car from street to sidewalk during a disturbance that drew national news coverage in May 1963. (princeton university archives) |

When I first read Selden Edwards ’63’s essay on one of Princeton’s great pranks, the holdup of the Dinky by four students on horseback in May 1963, I wondered what had become of students’ imaginations. Today’s pranks pale by comparison – fake e-mails, strange club initiation rites, occasional acts of nudity. Last year, senior class president Catherine Farmer ’03 sent an e-mail to her classmates stating that the comic Carrot Top would be Class Day speaker; after all, his hair screamed “Orange!” Her classmates were incensed until, that evening, Farmer announced that they would not hear from Carrot Top at all, but from comedian Jerry Seinfeld.

Not bad, but hardly up there with the likes of the train robbery, the admission of (nonexistent) William Oznot into the Class of 1969, or the antics of those wacky early Princetonians, who once brought a cow to the pulpit of the Chapel just before morning services, to protest mandatory attendance. “I have scoured my memory and come up with very little, which probably does support the ‘organization kid’ theory of today’s Princeton students,” one Princeton dean said recently.

In his Perspective essay, Edwards, the secretary of his class, describes the train robbery, on Houseparties weekend, as a spirited last hurrah to Princeton and youth, as one last tweak at tradition before graduation, when students would join that traditional, real world. But three days after that prank, Princetonians would make a similar statement, in a more sobering way. A three-hour disturbance that began with the toots of musical instruments and a few cherry bombs led to what news outlets from the Daily Princetonian to the New York Times called a riot involving 1,500 students. On campus and in town, the students lit fires, trampled gardens, tore up iron fences, broke windows, ripped off house screens, and sent a one-ton air compressor crashing into a lamp post. Some students blamed an absence of outlets for their energy and frustrations — a lack of cars, theaters, and girls. “We want, and need, a little excitement or adventure; a little of the feeling that we are men and alive,” one student wrote to the Prince.

The riot took place around the same time that thousands of people were marching in Birmingham, Alabama, for civil rights for black Americans, a fact not lost on President Goheen ’40 *48. “No one can justly complain about the emphasis given by the national press to this congruence of events,” he wrote to undergraduates. “We are too much inter-involved, community to community and nation to nation, to regard the senseless frenzy and random violence of the night of May 6 in Princeton as a matter of local consequence only. When so much is at stake . . . which calls for the best efforts of educated and thoughtful men, what appropriateness is there to be found in this kind of behavior by individuals whom nature and opportunity have so favored?”

In recounting the great train robbery, Edwards recalls a time of personal

transition – those expectant moments between youth and adulthood,

before the bonds of reality took hold. Four decades later, we know that

the transition that began in those days was so much greater.![]()

![]()