May 12, 2004: Notebook

Too many A’s?

University offers proposals to address grade inflation

Breaking ground—Politics

Money counts — even more than expected

Friends donate $10 million for new dorm

The road to success

Understanding tenure at Princeton

Ice and the Arctic: Finding the Northwest Passage

University offers proposals to address grade inflation

Grades at Princeton, like those at many of its peer institutions, have gotten progressively better in the last 30 years. A straight-B average in 1973 put a senior in the middle of the class; the same average put a student in the bottom 15 percent in 2002. And according to Dean of the College Nancy Weiss Malkiel, inflated grades do not draw out the students’ best work.

When the University began addressing grade inflation six years ago, Malkiel believed incremental change could reverse the trend, but departmental initiatives merely slowed it down. “The department chairs said, essentially, my faculty won’t act unilaterally to address this issue, but they will act cooperatively,” Malkiel says.

In April, the Faculty Committee on Examinations and Grading released its proposal for a common grading standard, limiting the number of A-range grades for each department to less than 35 percent in all undergraduate courses and less than 55 percent in junior and senior independent work. The levels are roughly consistent with the grades given in the five academic years from the fall of 1987 through the spring of 1992. Enforcement of the policy, Malkiel says, will “rely on publicity, persuasion, and encouragement.”

Student responses to the plan focused on two concerns, according to Undegraduate Student Government president Matthew Margolin ’05, who received more than 300 e-mail messages on the topic. The undergraduates worried that lower grades would affect their chances to compete for jobs after graduation, gain admission to graduate and professional schools, and win fellowships and scholarships. The grading proposals, students also said, could change the collegial atmosphere on campus. “Princeton is not cutthroat,” Margolin says. “Princeton is a welcoming, thriving intellectual community. I don’t think this can improve that in any way.”

Malkiel, who chairs the grading committee, acknowledges that the proposal is bold, but adds that it was not presented without considering the consequences. “We’ve worked very hard to inform ourselves about the likely impact of such a move,” she says. “I’ve consulted with deans of admission from top law and medical schools, employers who recruit on campus, and the major national fellowship competitions.” The University plans to explain what Princeton grades mean with a memo attached to every transcript it sends, and the effort to inform employers and schools will be sustained over time with reminders, she says.

Juewon Khwarg ’05, a history major who hopes to attend medical school, is wary of the plans. Conventional wisdom says that medical schools prefer to see an upward trend in a student’s grades, he says, and Khwarg believes a dropoff in his senior year could hurt his admission chances. “Thirty-five percent seems so rigid,” he says. “It doesn’t really take the teacher’s discretion into account.”

One of Khwarg’s premed classmates, Scott Grant ’05, had initial trepidation as well, until he saw the statistical breakdown of current grades. Grant is a chemistry major, and the natural sciences awarded A’s to 36.8 percent of its students in the last five years. So less grade inflation in other departments could improve Grant’s standing. “As long as there is documentation attached to student transcripts that Princeton has instituted this policy, professional schools will look at this favorably,” he says. “I don’t think it will have an adverse effect.”

The policy’s impact on the recent trend of grade compression is unclear. Will instructors just give more high B’s, or will they scrutinize the distribution of grades? C’s have become rare in Princeton coursework (7.3 percent in the last five years) and almost nonexistent in junior and senior independent work (2.6 percent and 4.1 percent respectively). “We’ve reached a different stage in our grading,” says Robert Tignor, chairman of the history department “The C used to stand for the average grade. It doesn’t anymore, and it’s not going to.” But Tignor says instructors are willing to take a closer look at, for instance, the difference between a B and a B-, based on the grade definitions included in the new proposals.

While lower grades may be hard for students to swallow, the grading

committee insists that the benefits will outweigh the drawbacks. “We

know that Princeton students represent the top talent in the nation,”

Malkiel wrote in a letter to students. “But such high and homogeneous

grades do not help you to distinguish your best work from your ordinary

work, and they do not motivate you to stretch to do the most imaginative

work of which you are capable.” ![]()

By B.T.

Money counts — even more than expected

Martin Gilens, associate professor of politics, has long studied citizens’ public-policy preferences. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski) |

The idea that wealthy Americans have political influence is hardly news, but according to new research from Professor Martin Gilens, the magnitude by which public policy favors people with high incomes is more overwhelming than previously known. The preferences of Americans in the 90th percentile of income affect policy twice as much as the preferences of people with average incomes, and three times as much as those in the 10th percentile — and these figures may be understated, since high- and low-income citizens agree on many policy issues.

Gilens, who joined the politics department last fall, found significant disagreement among the rich and poor on issues such as income taxes, free trade, Social Security reform, and affirmative action. On these kinds of “high-disagreement” issues, the probability of policy change increases dramatically as the percentage of high-income Americans favoring such change increases. But the probability of enacting change shows virtually no relationship to the preferences expressed by poor and middle-income Americans.

Wealthier Americans are more likely to participate in the political process, through active membership in political groups, personal expressions of opinion like letter writing, and voting, which explains some of the income bias. The U.S. also lacks the powerful labor unions and labor-affiliated political parties that empower lower-income citizens in some European nations. “We go to considerable lengths to try to limit the disproportionate influence of people with greater resources, through things like campaign finance laws,” Gilens says, “but it’s unclear how effective those efforts are.”

Previous research in the field has looked at government responsiveness to the public as a whole, but studying responsiveness to specific population subgroups is relatively new. Professor Larry Bartels, director of Princeton’s Center for the Study of Democratic Politics, used public-opinion data to assess biases in congressional representation in a 2002 study.

Gilens is using survey data collected from 1980 to 1998. Respondents were asked to express support, opposition, or a neutral position for hundreds of potential policy changes; Gilens allowed a four-year window after the time of each survey to determine whether Congress enacted each policy. His initial findings come from data collected from 1991 to 1998, and his next step is to go back further in time to compare the bias from different time periods. Future work may also include a look at biases based on gender, age, race, and party affiliation.

Gilens’s other research interests include changes in the media coverage of presidential elections since the dawn of the television age. In one recent paper, he writes that both news viewership and the amount of substantive, issue-based information in news coverage has declined in the last 50 years. Yet Americans are just as well informed about and able to identify the policy stances of candidates as they were in previous decades, thanks in large part to paid political advertising.

But there is a price. “While the increase in the amount of resources

that are going to paid advertising is a benefit, from the point of view

that it does have an education effect for the public,” Gilens says,

“that money has to be raised from somebody, and the candidates become

beholden to the campaign donors.” ![]()

By B.T.

A new dorm, funded by, from left, Peter C. Wendell ’72, Lynn Mellen Wendell ’77, Scott D. Cook, and Signe Ostby, will be called Wendell Hall. (Steve Castillo) |

Four friends together have donated $10 million to pay for the largest dormitory in the new Whitman College complex. The gift comes from charter trustee Peter C. Wendell ’72 and his wife, Lynn Mellen Wendell ’77, and Scott D. Cook and his wife, Signe Ostby.

The Wendells, who have six children, including Pyne Honor Prize recipient Christopher S. Wendell ’03, live in San Francisco. Lynn Wendell is a classmate of eBay president and chief executive officer Meg Whitman ’77, who along with her family, donated $30 million to the new college. Cook and Ostby live with their three children in Silicon Valley.

Peter Wendell, the founder and a general partner of the venture-capital firm Sierra Ventures, met Scott Cook, the cofounder of Intuit, when the two were students at Harvard Business School. Wendell’s firm subsequently provided venture capital for Intuit, maker of financial software programs, including Quicken and TurboTax; Cook now serves as a director of eBay.

The new dormitory, one of seven in Whitman College, will be named Wendell

Hall, in honor of Peter Wendell’s late parents, Virginia and Eugene

Wendell.![]()

Dean of the Faculty David Dobkin says research is paramount for obtaining tenure at Princeton. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski) |

The

road to success

Understanding tenure at Princeton

Tenured faculty posts at Princeton are among the most sought-after jobs in academia. Success rates for assistant professors seeking tenure vary by department; for example, a sample of science faculty hired from 1980 to 1994, profiled in a Princeton report on women in the sciences, showed that physics faculty had an overall success rate of about 20 percent, while the rate in the natural sciences was nearly 50 percent. As the recent cases of Andrew Isenberg (history) and Lynn Russell (chemical engineering) have shown, those who do not get tenure often make the headlines. Professor David Dobkin, dean of the faculty, talked about the tenure process with PAW’s Brett Tomlinson.

Tenure decisions are reviewed by the Faculty Advisory Committee on Appointments and Advancements, also known as the committee of three. Who serves on this committee?

The committee of three includes six members distributed across the University who are elected by the tenured faculty. Three of them must be from the humanities and social sciences, and three must be from the natural sciences and engineering. Obviously, they all have to be tenured full professors. In addition, the dean of the college, the dean of the graduate school, the provost, and the dean of the faculty [are ex officio members], and the president chairs the committee.

Are there enough tenured positions for all the assistant professors, or are professors competing for a limited number of openings?

The way we do it at Princeton, a position is a position, regardless of its rank. An assistant professor is really competing with him- or herself for tenure.

What is the significance of an assistant professor’s third-year review?

We view it as a place where we could do a mid-course correction. In fields where people write books, you want to make sure that the assistant professor is on track to get the book out. In fields where people set up labs, you want to make sure that the lab is coming along. In fields where people build teams of graduate students, you want to make sure that the grad students are getting engaged.

What factors are examined in the sixth-year tenure review?

Research, teaching, and service. Research is certainly the most important – the quality of the candidate’s scholarship. Teaching is also important, [especially when] the research is solid and the teaching excellent, or in a case where the teaching is weak, regardless of the quality of the research. The feeling is that if you are not established as a first-rank researcher, over time the teaching will decay. Similarly, a poor teacher may never improve. We try to project what the candidate’s future trajectory is, and research is the best indicator. Service is harder to measure because you have people who serve in different ways at different times in their career. We would expect an assistant professor to really be focused on his or her scholarship.

How do you measure research and teaching?

For teaching, we do evaluations at the end of each semester, so we have a history. For tenure, we have a five-year track record. We invite students to write us about professors – professors they liked, professors they did not like. We also look at advising – how many students are working with the faculty member? We often get input from those students.

For research, we largely rely on outside experts. We go to the experts in the field and ask them to rate the candidate’s scholarship and to place the candidate within a cohort of scholars in the discipline at the same stage of their careers.

Who submits the tenure request to the committee of three? Does the committee generally agree with the recommendation, or are there conflicts?

The department makes the recommendation. The committee of three does turn over recommendations. It happens. It is not a slam-dunk to go to committee. Often, when a decision is overturned by the committee of three, there is an acknowledgment by the department that this was not an open-and-shut case.

If the committee of three is inclined to overturn the department, the committee chair will invite the chair of the department and typically one other faculty member to answer questions and discuss it. It is a step in the process because we acknowledge that the department has done a great deal of work on the case. We also acknowledge that it is often easier for an anonymous committee to make a hard decision than it is for a department. They see the person, we see the paper.

In some cases, a faculty member will appeal a tenure denial to the Faculty Committee on Conference and Faculty Appeal. What are the guidelines?

That committee deals with the process. So a faculty member who says, “I’m much better than the committee thought; read the letters and interpret them for yourself,” will not be heard there. A faculty member who says, “I’m not sure the process was done fairly,” will be heard there.

Does a tenure rejection have a lasting effect on a professor’s career?

Princeton is viewed as a highly competitive place, a place with very

high standards. Obviously, your résumé is better if you

got tenure at Princeton than if you didn’t, but not getting tenure

at Princeton is not a large black mark. ![]()

Future academic buildings and dorms will be built within a 10-minute walking distance from the Frist Campus Center. (Steven Veach)

Construction of academic buildings and undergraduate dormitories will continue to take place on the Princeton side of Lake Carnegie for at least for the next 20 years, according to a recently released University development plan. But the University will consider developing its land in West Wind-sor, on the south side of Lake Carnegie, for nonacademic uses such as housing for graduate students, faculty, and staff.

To preserve Princeton’s pedestrian campus, planners drew a circle, centered at the Frist Campus Center, with a radius equal to a 10-minute walking distance. All new academic buildings and undergraduate dormitories will be built within that circle, according to the plan, which President Tilghman presented to the Board of Trustees last fall. Robert Durkee ’69, the University’s vice president and secretary, says the plan contrasts with previous forecasts that envisioned a “mirror campus” across the lake, with a mix of academic, residential, administrative, and recreational space.

Future academic construction may require changes to currently occupied campus space, Durkee says. Expanded engineering facilities could replace faculty and staff housing on Western Way. A new chemistry building could be erected on the site of the Armory. This summer the University hopes to hire an architect to design a bridge to span Washington Road near the Carl Icahn Laboratory.

Graduate student housing continues to be a concern. Replacing the Butler apartments is one possible remedy, as is the potential purchase of two properties currently owned by the University Medical Center at Princeton: the hospital’s 12-acre home on Witherspoon Street, and a nine-acre parcel on Bayard Lane. If the hospital decides to leave downtown Princeton, the University may acquire the site to build graduate student housing. Durkee says the West Windsor land between Alexander Road and the Dinky line would be ideal for faculty and staff housing if New Jersey Transit adds a stop for train or bus shuttle service.

The 20-year plan encompasses a small portion of potential long-term

Univer-sity development. When the University first purchased its lands

in West Windsor, it was with the idea that they might not be used for

a hundred years, which has proven to be the case. The new plan does not

look that far ahead. “We’ve learned enough to know that even

trying to look 20 years into the future is difficult,” Durkee says.

![]()

By B.T.

Princeton offered admission to 1,631 high school students this year – 11.9 percent of the 13,690 students who applied for a place in the Class of 2008. The applicant pool was the smallest in four years, dropping 13 percent from last year’s record of 15,725 applicants.

The Class of 2008 is expected to have approximately 1,175 students. Of those admitted, 11.2 percent are legacies, 9.2 percent are international students, and 47 percent are eligible for financial aid. Fifty-three percent are men, and 47 percent are women; 35 percent are from minority backgrounds. About 55 percent are from public schools; 35 percent are from private schools, and 10 percent are from parochial schools. About 35 percent were admitted through the early-decision process.

Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye said her first Princeton class possesses a diverse range of talents and personal qualities. “The entire admission staff was extremely pleased with the quality of this year’s pool,” Rapelye said in a news release. “We had difficult decisions to make. The admitted students stood out for their impressive accomplishments.”

For the Class of 2007, 9.9 percent of applicants, or 1,570 students,

were accepted; 1,171 students matriculated. ![]()

By B.T.

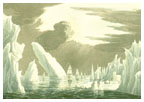

Photo: courtesy John Delaney |

For centuries, Europeans sought a commercial sea route through the ice-clogged

Arctic waters of Canada. Such a route would shorten the distance ships

would have to travel to trade with the Orient, and avoid the sometimes-treacherous

waters around the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn. In an exhibit at the

Leonard L. Milberg Gallery at Firestone Library, “Of Maps and Men:

In Pursuit of the Northwest Passage,” the 400-year history of the

search is documented in maps, books, and photographs. The maps include

Gerhard Mercator’s “Septentrionalium Terrarum descriptio”

(1595), considered the first full Arctic map, in which the North Pole

is depicted as a huge magnetic rock. Also on view are several spectacular

images of ships at sea, including “Passing Through the Ice, June

16, 1818 Lat. 70.44 N” (above), drawn by Sir John Ross.![]()

A new gateway and a trio of congressional visitors highlight the festivities planned for Reunions 2004, May 27—30. The Class of 1979 will lead the P-rade onto Poe-Pardee Field through the triumphal arch of the newly constructed upperclass dormitory, and this year’s alumni-faculty forums will take participants inside the Beltway with appearances by Senators Paul Sarbanes ’54 and Bill Frist ’74, and Congressman James Leach ’64.

On Friday, Frist, the Senate majority leader, will speak on a panel about global health issues, and Sarbanes, cosponsor of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, will discuss corporate ethics. On Saturday, Leach joins Platte Moring III ’79, staff judge advocate for the U.S. Army in Afghanistan, to examine the impact of September 11 on law.

The 16 scheduled panels cover national news, global concerns, lifestyle

choices, and campus issues. “Volunteers from the major reunion classes

have put together the panels and recruited their classmates,” says

Andrew Gossen ’93, associate director for alumni education. “That’s

the real reason why this works as well as it does.” Alumni and faculty

panelists are subject to change. A full Reunions schedule is available

on the Alumni Council’s Web site at http:// alumni.princeton.edu/Events/Reunions.asp.

![]()

By B.T.

Princeton has postponed increasing its student body by one year to 2007, because construction of Whitman College will not be complete until then. “We knew it would be a complicated and challenging undertaking. It’s proven to be even more complicated and challenging than we initially estimated,” says Vice President and Secretary Robert Durkee ’69.’”

English professor Lee Mitchell was put on a one-year unpaid leave of absence, effective July 1, after a University audit found discrepancies in an English department fund he oversaw. Mitchell, who is master of Butler College, also resigned that position effective July 1.

Jeffrey Herbst ’83, professor of politics and international affairs; Stephen Kotkin, professor of history; and David Rousseve ’81, choreographer, were recently awarded Guggenheim Fellow-ships. The fellowships, which averaged $36,000 in 2003, are given to advanced professionals in midcareer.

The University of Chicago has chosen Danielle S. Allen ’93 as dean of humanities, and in that position she will oversee 15 departments. Allen, 32, has been at Chicago since 1997. In 2001 Allen was awarded a MacArthur Fellowship. Her second book, Talking to Strangers: Anxieties of Citizenship Since Brown v. Board of Education, will be published this fall.

Katherine Grim ’04 and Robin Williams ’04 have been awarded ReachOut 56 Fellow-ships. Williams, a Woodrow Wilson School major and photographer, will focus on seven case studies and depict through photography and narrative the personal stories of individuals affected by government policy. Grim, a religion major, will work as a manager at a Newark training program that helps talented teenagers who have a strong interest in the arts. ReachOut 56 is funded by the Class of 1956.

Four Princeton students have been named Goldwater Scholars. They are: math majors Matthew Satriano ’05 and Van Molino ’05; chemistry major Katharine Moore ’05; and Jordan Paul Amadio ’05, a physics and biophysics major and PAW contributor. The scholarship program encourages outstanding students to pursue careers in mathematics, the natural sciences, and engineering.

An exhibit featuring the collection of John Wilmerding, professor of

art and archaeology, is on view at the National Gallery of Art, in Washington,

D.C. The exhibit, “American Masters from Bingham to Eakins,”

closes October 10, 2004. The exhibit’s Web site can be found at

www.nga.gov/ press/2004/204/images.htm. ![]()