Princeton University Archives |

A

great expedition

An explorer’s biographer makes his own wondrous

discoveries

By Landon Y. Jones ’66

Landon Jones ’66 is the author of William Clark and the Shaping of the West, which was published this month by the Hill and Wang imprint of Farrar Straus Giroux.

It was not exactly a “Eureka!” moment. But it was as good as it gets for a writer rooting for truffles in the depths of C Floor of Firestone Library. My quest had begun a few weeks earlier when, in the thick of research for a biography of William Clark, the explorer and Indian agent, I had come across an intriguing entry in the daybook kept at his office in St. Louis. Amid a numbingly dull parade of entries on weather and river traffic, a clerk suddenly erupted that the steamboat Atlantic had arrived on June 12, 1830 with “the eccentric and no less strange Woman, Mrs. Ann Royal! Her turbulence & wanton vehemence, excites curiosity, while it keeps from her, the real friendship of all.”

Who was Mrs. Ann Royal? Why did she incite such passion in this otherwise phlegmatic clerk?

A hurried search of the library catalog produced no hits. Nor did Google. The mysterious “Ann Royal” might have eluded me forever but for the fact that Firestone’s stacks are as open to explorers as the West once was for Lewis and Clark. I had been looking at a book shelved in the history section when my eye fell on the tier immediately above it. Sitting there, seemingly awaiting my glance since it was published in 1909, was call no. 1083.791.73, The Life and Times of Anne Royall, by Sarah Harvey Porter. Eureka!

The woman whose misspelled name could be recognized by a blind pig, but not a searchable database, was Anne Newport Royall, a crusading journalist, travel writer, and early feminist. She was vilified and once convicted as “a common scold” but managed to interview many prominent Americans of her time, including every president from John Adams to Franklin Pierce. Clark, who had squared off with the Lakota Sioux and countless grizzly bears, was so afraid of facing her that he hid. Mrs. Royall resorted to tracking him down in his back office, as she wrote, “cooped up like an old rooster.”

This was just one of the many instances when, in the course of four years of research, much of it at the Princeton University Library, the force of serendipity seemed to play as large a role in my progress as any computer-research device. On another occasion I was investigating the series of enormous earthquakes near New Madrid, Missouri, in 1811—12. These quakes, the largest known in North America, knocked down chimneys in St. Louis, rang church bells as far away as Charleston, South Carolina, and caused a section of the Mississippi River to heave, buckle, and briefly flow backwards. Clark had written about the earthquakes in his letters.

My system registered an unmistakable seismic jolt one day in the photocopying room on B Floor of Firestone. I had commandeered a copying machine and begun to clear off the papers left by a previous user. Then I noticed that one of the discarded sheets contained the beginning of a scholarly article: “Seismol-ogists’, Geologists’ & Engineers’ Different Perspectives on the N.M.S.Z. [New Madrid Seismic Zone].” There was a large coffee stain on it. It immediately disappeared into my folder.

I spent most of my research time at Princeton below the earth’s surface on C Floor of Firestone, which houses in open stacks hundreds of volumes assembled over many years. Occasional field trips would take me to more exotic outposts in the library’s realm. My first expeditions were to the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, which has among its holdings the amazing McCarter & English Indian Claims Cases collection, an archive of letters and other historical documents used by the Newark, New Jersey, law firm of McCarter & English while representing four Mississippi and Missouri river tribes between 1958 and 1970.

The law firm had dispatched researchers to the National Archives to produce transcripts of the microfilmed Indian records there. As a result, I was able to use neatly typed copies of dozens of letters written by Clark, as well as verbatim transcripts of speeches made by prominent chiefs of the time, such as Keokuk. For the first time I could hear the voices of real Indians and their real antagonists emerging from the pages.

Other trips took me to the Geosciences & Map Library in Guyot Hall in order to find out about Big Bone Lick in Ohio, where Clark collected fossils for Thomas Jefferson. At the Marquand Library of Art and Archaeology I researched 19th-century painters like Chester Harding, Charles Willson Peale, and John Wesley Jarvis, all of whom executed portraits of Clark.

The more I found, the more I wanted. I issued requests to the mysterious Annex libraries for bound volumes of Niles’ Weekly, a 19th-century journal, to find out about Clark’s activities during Andrew Jackson’s inauguration in 1829. Requests for farther-flung books went to Borrow Direct, a consortium that magically whisked books off the shelves at any of six other Ivy League libraries in a few days.

One of the curiosities of William Clark’s life is that he has been defined historically by a series of paired relationships – first with his famous older brother General George Rogers Clark, and then with Meriwether Lewis and with the Indian woman Sacagawea. But the most significant of Clark’s relationships in the second half of his life was with his contemporary Keokuk, a Sauk war chief and rival of the better known Black Hawk. Clark met with Keokuk dozens of times over the years and sought to enhance the chief’s status by frequently giving him gifts. One of these was a Presidential “Peace Medal,” a medallion bearing the likeness of James Madison, Class of 1771, given to Keokuk after the War of 1812.

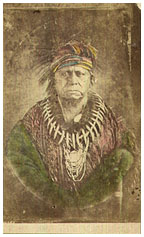

The Library owns a daguerreotype of Keokuk and also owns the peace medal he is wearing in the photograph. After I finished my biography, I went to the Rare Books and Manuscripts room this spring and asked to see the peace medal. A small cardboard box was brought out; in it was Keokuk’s medal, wrapped in clear plastic. It is solid silver, about two inches in diameter, heavier than you might expect.

The medal is an object rich in memory. Keokuk would have worn it to

the 1834 treaty council when, as transcribed in the McCarter & English

papers, he said, “We have sold most of our country to the President,

our land is small, the game is getting very scarce and it takes all our

money to support us, and yet we are frequently in want & many of us

suffer.” Reading that, and holding Keokuk’s medal, I wondered

if the next story to tell was somewhere in my hand.![]()