June 8, 2005: Features

Have an opinion about this issue of PAW? Please take a minute to click here and fill out our online survey. It’s an easy way to let the editors know what you like and dislike, and how you think PAW might do better. (All responses will be anonymous.) |

(© DAVID BINDER)

GROWING

UP

THE

CAMPUS ACTIVIST

LIFE

AFTER PRINCETON

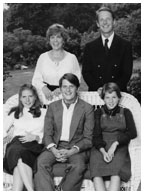

THE MASSIE FAMILY From top, sons John, left, who is entering his junior year in high school, and Sam, who will attend Yale in the fall. Massie with wife Anne Tate ’78 and their daughter, Katie. |

‘What

it means to be human’

For Bob Massie ’78, a new life of waiting

and reflection

By Pam Belluck ’85

Robert Kinloch Massie IV ’78 came to terms long ago with the mysterious vulnerability of the human body – specifically, his.

He was born a hemophiliac, started showing bruises from bleeding joints by the time he was 4, wore leg braces until he was 12, and used an electric cart to get around at Princeton. The year he graduated from Princeton, he received an unwelcome gift: HIV-positive blood in one of the daily transfusions he needed to keep his hemophilia from bleeding him to death.

But the HIV didn’t kill him. To the contrary, he became something of a legend in medical circles because he has never shown any symptoms of AIDS. Doctors put him under the microscope, and the man who spent a lifetime receiving blood from others became a source of blood himself, shipped to researchers around the world to help them decipher what it was about Massie’s immune system that made him resistant to AIDS. “They would be saying life expectancy is five years, and I would be at the five-year mark; seven years, and I would be at seven years,” Massie says. He did not feel invulnerable; he did feel lucky. All the while, Massie, a man whose deep intellectual curiosity was matched by a boundless energy, built a full and active life, becoming an Episcopal priest, traveling to South Africa and writing a book about apartheid, running for public office, teaching at Harvard Divinity School, and leading a nonprofit organization.

But a few years ago, Massie fell victim to a different scourge: liver disease. Another blood transfusion years earlier had given him hepatitis C, which eventually caused cirrhosis, a severe and deadly scarring of the liver. He will need a liver transplant to save his life.

Today, Massie occasionally closes his eyes when he speaks — it helps him focus better on what he’s saying when he gets tired. Besides the physical symptoms of his illness — “you feel like you’ve had a very, very bad flu almost all the time,” he says — there are mental repercussions too, something Massie calls “brain fog.”

“It is to the brain what extreme fatigue is to the body,” Massie says, sinking into an overstuffed chair near a fire glowing from the hearth in his Somerville, Mass., home. “You just go through a period where everything slows down. You’re still very awake, but you can’t think about things as quickly. Your range of view is foreshortened a bit.”

He is well aware of the paradoxes in his life, and out of a lifetime of illness, he has extracted a philosophy of optimism, resilience and a refusal to wallow in self-pity. “In some sense, I meet all the characteristics of privilege — I’m a straight, white, Anglo-Saxon Protestant male,” Massie says in his low, warm voice. “But what I identify with inside is all the people who have to contend with fear, this sense of being on the margin.”

Early on, his parents, writer and scholar Suzanne Massie and Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer Robert Massie, decided to be candid with their son and with others about his illness, which, with daily transfusions and frequent trips to the hospital, would come to govern so much of the way they lived. In a groundbreaking book about the family’s experiences, Journey, they described dealing with others who were ignorant or wary of their son’s illness. “Sometimes my mother would find people staring at her in grocery stores, wondering whether she was abusing me because I had some scary-looking bruises,” Massie explains. “You have to determine how you’re going to react to people. One choice is to be more hidden and pretend like the illness isn’t there. Secrecy offers the illusion of safety, but in the end, openness will help build relationships.”

At Princeton, Massie was open about his illness as well. To help him get around, the University installed outlets where he could charge his electric cart, and a post where he could chain it. McCosh Health Center prepared for his visits “so that five or six times, when I had a knee bleeding and needed to stay put, the infirmary gave me a place where someone brought me meals and something to drink while I worked on my homework.”

He was “absolutely the slowest member” of the swim team, he recalls. But most of Massie’s energies went into being a student activist, quitting Ivy Club to protest the selective eating clubs, and pressing the University to divest from South Africa.

He says that there are still Princeton policies that he would like to change. “Naming all these buildings after the capitalists who paid for them — I think that sends a very bad signal,” Massie says. “It’s recognition based on who’s got the money, and that’s not Princeton in the nation’s service.”

Massie pauses for a moment and chuckles at his impassioned tone. “That,” he says, “is my little ‘Bob is not dead, he still has things he wants to say’ comment.”

His Princeton years also spurred him to a religious epiphany, Massie says. His grandfather was a minister, but Massie at first rejected that path for himself. “I knew that I was just too flawed a human being. I was too ambitious, too noisy,” he says. Then, as a history major, he spent a summer in France between his junior and senior years, researching his senior thesis on French leftist politics. Someone asked him if he believed in God.

“I found myself saying ‘God, if you’re out there, I’d like to feel more of your presence,’ and truthfully, I began to feel what can only be described as the warmth of the love of God,” Massie says. When he returned to campus, newly spiritual, “people thought something weird had happened to me,” he remembers. But he went on to divinity school after graduation, choosing Yale Divinity “because the people who couldn’t hear the divinity could still hear the Yale.”

During his first few months at Yale, in the fall of 1978, Massie got “overwhelmingly sick with an undiagnosable illness,” he recalls. Yale’s hospital couldn’t figure out what it was, but it was so severe that Massie withdrew from school and went home for the rest of the year.

Years later, in 1984, Massie, by then married and a junior Episcopal minister, was told matter-of-factly during his participation in a hemophilia research study that he was HIV-positive. It turned out that he had gotten the virus from a transfusion in 1978, and that his mysterious illness that year was almost certainly his body’s initial violent reaction to HIV.

He was not really surprised. “I didn’t react to it one way or the other,” he says. “I’ve received the blood of tens of thousands of people, maybe hundreds of thousands of people, and I have so many things” — including antibodies and infections — that came from that blood. Plus, he had no symptoms of AIDS. He and his wife, who had moved to Boston so she could teach and he could attend Harvard Business School, got extensive medical counseling as they prepared to have children. They had two healthy boys: Sam, who will be a freshman at Yale in the fall; and John, a junior in high school.

It was a surreal position to be in, confronted by 1980s AIDS hysteria everywhere he turned, reading the screaming tabloid headlines, hearing the proposals to quarantine AIDS patients. Massie remembers that some of his friends had the attitude: “Isn’t it a shame that Bob doesn’t realize he’s going to die soon, and he should act like it.’” Massie continued on. He received a doctorate in business administration from Harvard in 1989 and began teaching at Harvard Divinity School. He was sufficiently optimistic about his prognosis that he ran for lieutenant governor in 1994, attracting quite a bit of notice, this minister with HIV who played the banjo at campaign rallies and barnstormed in a ramshackle station wagon. “At first it was like, ‘Who is this? Some kind of Make-a-Wish Foundation last-ditch candidate?’” Massie remembers. “I would say, ‘I want to remind you that it’s not like I’m mortal and you’re not.’” He won the Democratic primary, but his ticket lost to Republicans William Weld and Paul Cellucci.

Two years later, Massie became executive director of the Coalition for Environmentally Responsible Economies (Ceres), an organization of more than 80 environmental groups, public interest groups, and investors and analysts who represent more than $400 billion in invested capital. He created guidelines to keep track of the environmental, economic, and socially responsible progress of companies, countries, and nongovernmental organizations. And he started a program to encourage corporations to measure and control their greenhouse gas emissions.

It was around this time that one of Massie’s Princeton roommates, Stephen Chanock ’78, an infectious disease specialist, suggested that he see a doctor because he had stayed so “persistently well” with HIV. So Massie walked into Massachusetts General Hospital and presented himself to Bruce D. Walker, director of the AIDS division at Harvard Medical School. “He was basically coming in and saying, ‘I want to get an opinion about what’s going on — and maybe you guys want to study me,’” Walker says. “At first I had my doubts about whether he was really infected, but we confirmed that very quickly and discovered that the viral load on him was below the limits of detection. That really seemed to go against what we thought HIV did. It made us extremely interested in how he was able to succeed in combating this, where others were clearly failing.”

Walker says that in most HIV patients, cells that fight infection — what he calls the “infantry” — are present, but what’s missing are the “generals,” cells that tell the infantry what to do. With such an “uncoordinated defense,” he explains, the patients succumb to AIDS.

But Walker and his colleagues discovered that unlike most HIV patients, Massie had both infantry and generals in abundance. “For me it was the first indication that the immune system might actually be able to get the upper hand against HIV,” Walker says. “He’s really the person who allowed for that discovery to happen. Bob was really the sentinel case.” The doctors did extensive research on Massie — aka number 161J — and have sent his blood to interested laboratories around the world.

The doctors launched an experiment to see whether the “general” cells could be saved if patients received strong drugs at the beginning of their HIV infections. They studied 14 people, Walker says, and found that “by treating them early they got the kind of immune response that Bob Massie has.” Ultimately, however, all but two had a recurrence and were started back on treatment. “We’re trying to understand what happens to make them lose control,” Walker explains. To determine whether Massie really was an anomaly, the doctors also recruited other HIV-infected but asymptomatic patients whose viral loads were very low or undetectable, and are studying their genetic makeup and immune systems to see what they have in common. Walker estimates that such patients comprise about 1 percent of all those with HIV.

“It is now clear that Bob Massie’s immune response can be replicated in other people,” Walker says, although researchers still are not sure how Massie came to have such an immune response. More importantly, he explains, studying Massie was “pivotal in terms of our thinking of how to make an HIV vaccine. When a vaccine gets developed, it’s going to incorporate the kind of immune response that Bob has.”

The findings of the research made Massie have “less of a kind of survivor’s guilt and [feel] more like at least he could make a contribution,” says Anne Tate ’78, who married him in 1997 (Massie and his first wife, Dana Robert, divorced in 1995). Tate, an architect, notes that when people realized that Massie had HIV but no symptoms of AIDS, they “would look at him sideways — [they would think] this person’s dying and that person’s dying — how come you’re not dying?” When they actually started to study him, she says, “the fact that he was doing so well became not just a private victory but a public asset because there was information that would help people.” Massie often joked that he would become known not for his accomplishments in his career or public service, but for his role as 161J.

Neither Tate nor Katie, their 6-year-old daughter, has the virus, and for years, Massie lived a life full of vigor, traveling and climbing mountains.

The onset of liver disease required Massie to relinquish much of that life. He gave up his fast-paced, globe-trotting schedule after his health forced him to bow out on the eve of a speech in Johannesburg in 2002. Two years ago, he had to quit his job altogether, except for a few consultations by phone.

It became clear that, at some point, Massie would need a new liver. At first, it appeared that not many hospitals would perform liver transplants on HIV-positive patients because most were assumed to have a limited life expectancy. “I was one of the cases that helped them say this rule doesn’t make sense,” he says. For months, Massie and his wife searched for someone able to donate part of his liver, speaking to relatives, friends, and members of their church, keeping them updated on his condition via a Web site (http://bobmassie.org). Their pavement-pounding paid off, and doctors have told them there are now four qualified contributors.

But there is a catch. Although Massie’s condition is serious, his liver is not debilitated enough to allow him to have the transplant. Even with willing donors, doctors will wait to perform the surgery because they consider the risk of surgery for both the donor and the recipient to be greater than the risk of not doing it.

So Massie, now 48, is floating in a painful limbo, waiting until his health gets even worse before getting a chance at a procedure that might make him better.

“It’s forced me to make the transition from what my family used to call ‘the non-stop big deal,’ going from someone who was very busy, which in itself is a sign of status,” Massie says. “To go from that to [saying] ‘I have all the time in the world, I’m not doing anything’ — that requires an adjustment. [It’s] the fatigue and the inability to translate the many ideas I still have into action. I’m not the head of the organization anymore. I have an idea, but I don’t have the staying power to make it happen.

“When I had physical limitations I could always take refuge in the fact that I could read or think,” Massie says. “Now there are periods of time when I can’t rely on that.”

Sometimes, he says, he drifts off during phone conversations or doesn’t recall what someone wrote in an e-mail. “Hemophilia was really about battling physical limitations, and either learning to live with them and overcome them, or not,” Massie says. “HIV was a challenge to the heart and soul in a different way, with really no physical symptoms, but many spiritual and emotional consequences. This hepatitis C has required me to get to a much deeper level of understanding of what it means to be human. We are not just our bodies, and we are not just what we think.”

Massie’s liver disease has also presented Walker and his research team with another mystery. “Unfortunately, it’s an increasingly frequent story — hepatitis C is a major problem for people who have been HIV-infected,” Walker said. “We’re seeing a lot of morbidity now from people who have HIV and hepatitis C.”

Massie’s case “remains incredibly perplexing. He does a phenomenal job of controlling his HIV infection — he’s as

impacted by HIV as someone who’s not infected. But his Hepatitis C has become so severe that it’s destroying his liver,” Walker says. “At the same point in time, the immune system

is doing such a great job with one virus and such a terrible

job with another. It is something that we’re desperate to understand.”

These days, Massie spends his time reading voraciously — ordering books online and using the Internet to learn about everything from the history of film to the Middle Ages to global exploration. He has mastered a mean recipe for popovers.

“He is not typically a very patient person,” Tate says. “But I have never seen anyone who has this capacity to suck it up and adjust and move forward. Everything that happens, he digs into it and digs out of it.”

Faith has undoubtedly helped Massie frame his predicament. “A critical portion of my faith has to do with the idea of grace, that we are the constant recipients of wonderful things from each other and from God, that we’re not fully aware of or that we take for granted,” he says. “No matter how screwed up we become, how many failures we commit, in the end the default position is a position of forgiveness and grace.”

To be sure, every once in a while, usually in the middle of the night, Tate acknowledges, her husband says he is tired of his predicament, “of being me.”

But on balance, Massie says, “I have three wonderful, incredible children; I have an amazing, brilliant wife; I live in an extremely comfortable home; I have people who call me up just to talk about interesting things; I am able to walk, which I was not able to do through my whole childhood. I even have time now, which many adult Americans don’t have.”

There may be other paradoxes on Bob Massie’s horizon.

Walker says the transplant surgery requires suppressing Massie’s immune system, and that could suddenly lessen his resistance to HIV. Symptoms could start emerging, and “we’ll definitely be monitoring that incredibly closely,” says Walker. He says he is comfortable that existing HIV medications would be able to treat any symptoms that Massie might develop.

By the same token, Massie says, “There’s also the possibility that you feel much better and that, because a new liver would make a clotting factor, my hemophilia might be cured. That was something that I have never imagined from the moment I was born. I have the possibility that there’s a whole new life on the other side of this.”

He voice flutters slightly, as if he is trying to visualize a life without fatigue or pain or brain fog.

“That,” Bob Massie says quietly. “Wouldn’t that

be a peculiar twist?” ![]()

Pam Belluck ’85 is New England bureau chief for the New York Times.