|

|

November 16, 2005: Features

(Selçuk Demirel)

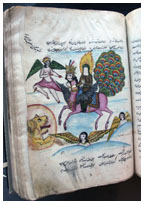

Princeton has one of the world’s finest collections of Islamic manuscripts, including this chronicle of Islamic history from the 18th century, a gift from Richard and Rosalie Norair, both members of the Class of 1976. (Denise Applewhite/Office of Communications) |

The

paper chase

As the cost of acquiring manuscripts soars, Princeton increasingly

finds itself on the sidelines

By Merrell Noden ’78

Last year, with mortality on his mind, Norman Mailer decided it was time to shop his papers around. Fortunately, Mailer didn’t have to do this literally, for in his 82 years, he seems to have been quite a pack rat, collecting — along with one National Book Award, two Pulitzers, and six wives — more than 10 tons of papers, including a dozen finished screenplays and 25,000 letters. So where did the Brooklyn-bred, Harvard-educated, Cape Cod-dwelling enfant terrible of 20th-century American letters choose to place this coveted collection? In Austin, Texas, at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas.

“Norman is not a sentimental man,” says Glenn Horowitz, the New York bookseller who brokered the deal.

Mailer kept a straight face as he described his long-standing affection for the Lone Star State. He noted that during his years in the Army he served with a number of Texans and learned a “good bit about Texas and Texans, so that may have been a factor in choosing the University of Texas.” A bigger factor, surely, was the fact that the Ransom Center was willing to pay him $2.5 million for the archives.

That figure is eye-catching for a number of reasons, but none more than the fact that it is almost three times the $835,000 budgeted by the Princeton library system this year for rare books and manuscripts (though additional money often can be found from donors and other sources) — a difference that has some Princeton librarians feeling frustrated. Princeton, says Ben Primer, the associate University librarian for rare books and special collections, “has increasingly fallen behind its peers in its ability to acquire rare and unique materials, particularly in the area of modern literary manuscripts.”

In the past 15 years, the most the department has been able to muster for a single literary archive was $250,000. To get some idea of what that will — or, more accurately, won’t — buy, recall that in 2001 Jim Irsay, the owner of the Indianapolis Colts football team, paid $2.43 million for the tattered, 120-foot-long manuscript of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and that more recently Susan Sontag sold her papers to UCLA for $1.1 million. When a bidding war for Allen Ginsberg’s papers broke out between his alma mater, Columbia, and Stanford, Ginsberg put school spirit aside and sold them to Stanford for nearly $1 million. That was back in 1994, and prices have only escalated since then.

Increasingly, Princeton curators have found themselves standing glumly on the sidelines. “Because we don’t have a lot of money, dealers don’t even bother to come,” says Primer.

Horowitz confirms that. He did not call Princeton about the Mailer papers. Why bother? He knew that Princeton almost certainly would not match the kind of money he could expect to get from the Ransom Center. Horowitz believes it’s a simple difference of priorities. “At Texas,” he says, “they have identified the pursuit of literary scholarship through original manuscripts as a way of being in the world. Princeton, for whatever reason, does not seem to share this sentiment.”

Ben Primer’s office in the rare books section of Firestone’s ground floor is, as you might expect, wall to wall with beautiful old books. These particular books were once the collection of a Philadelphia stockbroker named Morris Parrish, a member of the Class of 1888, who is notable not only because he chose to donate this painstakingly assembled collection of some 6,500 Victorian novels, but because he did so having spent less than a year at Princeton. It was Princeton’s good fortune that, when he died in 1944, Parrish left his collection to the University. People were more likely to do that sort of thing back then than they are now.

It should not surprise us that the world of book and manuscript collecting has changed. It’s still a fairly insular world, and one that places a huge emphasis on discretion. “We don’t like to talk about numbers,” says Don Skemer, Firestone’s curator of manuscripts. “It’s all very confidential. And we don’t want to say things that make it sound as if we are in cutthroat competition with other institutions. That would be tacky.”

And as Dr. Thomas Staley, the Joyce scholar who is director of the Ransom Center, points out, there are strong practical reasons for honoring this code of discretion: “You don’t want people to think you are very wealthy because you don’t want to inflate prices. But on the other hand you don’t want people to think you’re poor because you want them to call you first.”

Make no mistake: Staley is near the top of many a dealer’s speed dial. Not only does the Ransom Center have extremely deep pockets, its money has enabled Staley to build a superb collection, cared for by 100 curators and extensive conservation laboratories. The Beinecke Library at Yale and the Houghton at Harvard are also flush. That’s not new; it’s been a fact of life around Firestone for years. “Our Department of Rare Books and Special Collections does not enjoy the large, long-standing endowments of many of our peers, which means that we can hardly ever compete for collections like Susan Sontag’s papers or the archives of the Paris Review,” allows University Librarian Karin Trainer, via e-mail. “To provide a permanent source of support for these acquisitions, we need to increase the size of the department’s endowment, and I’m trying very hard to do that.”

What makes her task more of a challenge than ever before is how many more players there are now, and how flush some are with absolutely crazy money. Pharmaceutical money supports the Lilly Library at Indiana University, while a good chunk of whatever oil money doesn’t go to the Ransom ends up at the Bridwell Library at Southern Methodist University, in Dallas. The Bridwell recently celebrated the acquisition of its 1,000th incunable (books from the dawn of printing, defined as before 1501), though Primer cautions that that’s not necessarily a measure of a collection’s quality. “There are incunables worth having and others not [worth having],” he says with a shrug. “But it does tell you something about the mentality of some of these people who are collecting.” According to an online guide to its special collections, Princeton owns about 500 incunables, and another 150 reside in a collection that is owned by William Scheide ’36 and housed in Firestone Library.

In 1979 Emory received $105 million in Coca-Cola stock, which it has used to build a superb collection of modern poetry, and of modern Irish poetry in particular. In 1997, it bought the English poet Ted Hughes’ archives for a reported $600,000, and it has since added other important troves of his papers, which will attract not only scholars of modern British poetry, but also those studying Hughes’ wife, Sylvia Plath. In 2003 Emory acquired the papers of Nobelist Seamus Heaney, which join those of Yeats, Beckett, and Princeton’s own Paul Muldoon, among many others.

“It’s not just that they have Coca-Cola money [at Emory],” explains Skemer. “It’s also that they’ve chosen to focus it narrowly, to corner the market on contemporary Irish literature. ... But we [at Princeton] don’t do that, shouldn’t do that, and can’t do that,” Skemer continues, “because Princeton is a much more complex university. No one here wants us to do that. I like to say that our collections are as diverse and complex as the interests of the faculty and students. We can’t put all our eggs in one basket.”

Despite the mandate to collect widely, there are, of course, areas where Princeton more than holds its own, including Islamic manuscripts, 11,000 of which reside in Firestone, making up the largest collection in North America and one of the finest in the world; contemporary Latin American writers; and the archives of many of the top publishing houses — not to mention the papers of F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17, whose daughter, Scottie, donated them to the library in 1950. The extensive, privately owned Scheide Library includes the first four printed editions of the Bible, including the Gutenberg Bible, which Scheide makes available to scholars and researchers.

Why should we care that Mailer’s papers ended up in Austin, rather than in Princeton? Is this just an arcane topping contest between bibliophiles, or is something important at stake?

Discussing why he chose Texas, Mailer also gave another reason. The Ransom’s awesome holdings, which for some time have exerted something like a gravitational pull on other contemporary authors, make it more likely that in the future other writers will want to be part of this amazing collection. This makes perfect sense: Who wants to be a library’s lone big writer when you might be in the thick of things? The same goes for those Irish poets at Emory: It makes sense for them all to be gathered in one place.

The Ransom Center, which was founded in 1957, has pockets as deep as Texas is big, with much of it coming from oil. Staley, its director, reports to the president of the University of Texas, not to the head of the UT library system. It has its own budget and can do its own fund raising. “It’s not just luck,” says Staley. “We’re very systematic. We have a list of 475 authors that our young curators watch very carefully to see what the reviews are, and then we collect their books and then eventually we say, ‘Is this somebody whose archive we might like to pursue?’ This is a very elaborate program here.”

It has paid off. Not only does the Ransom possess treasures like a Gutenberg Bible (there is one in Scheide’s collection at Firestone) and the first photograph, it competes in countless other fields, driving up prices for all. “Our strongest area is probably in the British [writers],” says Staley, sounding positively jovial. “We have Julian Barnes, we have Penelope Lively, Penelope Fitzgerald. Tom Stoppard’s papers are here. So are David Hare’s. The Booker nominations came out yesterday, and three of the nominees are already in our archive.”

And it’s not just literary properties that make the Ransom such a juggernaut: In 2003 the center paid $5 million for the Watergate papers of Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. There’s no ignoring the Ransom’s influence on the market. That $5 million price tag has upped the ante for political papers. “There are now political figures who are approaching me about paying for their papers,” says Primer. “One called recently — I can’t say who it is — who believes his papers are worth $1 million.”

Much as it might pain Princetonians to admit it, this is an open marketplace. If it’s gotten more crowded and as a result more competitive and costly, well ... who are we to complain? Fifty years ago, no one at Princeton was shedding a tear for Texas or Emory when those universities were mostly on the outside looking in as troves of manuscripts headed to rich old institutions in the Ivy League.

When you list a university’s most treasured assets — the things that distinguish it from other universities and make it great — the strength of its library ranks near the top, right up there with its faculty and its students, past and present. “What makes Princeton different from any other academic library is the unique material we have in our special collections,” is Primer’s answer. There’s a lot of intellectual buzz that goes with possessing a superb library and having a parade of top scholars visiting campus.

Princeton, says Primer, is falling behind in two key areas: First, in the area where Texas is so strong, contemporary American and English literary materials. That’s due not just to direct competition with the Ransom, but for the related reason that the Ransom drives prices up. Second, the University is lagging in obtaining specific, high-ticket research materials sought by various departments. The Martin Luther King papers, for instance, which the King family is trying to sell through Sotheby’s, are expected to go for somewhere between $20 million and $30 million. (Representatives of Firestone were invited up to Sotheby’s to salivate, but have no hope of obtaining this trove.) Columbia recently won a bidding war with Duke for the Human Rights Watch archive; the Buckminster Fuller archive was pursued by Firestone but ultimately sold to Stanford for more than $1 million.

Another change in the manuscript-collecting world is the role of agents. “Writers didn’t always have agents,” says Primer. “They do now. Literary figures know the value of their materials. They choose to sell them. I don’t blame them.”

Of course, writers have often needed income beyond what they gain from their art. In Elizabethan England, they found patrons if they were lucky, and in the middle of the 20th century some of the most distinguished American writers — Faulkner and Fitzgerald, for example — routinely swallowed their pride and wrote for Hollywood.

These days, the route many writers take is to teach at a university, which keeps them off the breadlines but hardly makes them wealthy. Though several generous professors have chosen to donate their papers to Princeton, including Edmund Keeley ’48, the former head of the creative writing program, and Arcadio Díaz-Quiñones of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese Languages and Cultures, the University has a rule forbidding the library to pay faculty members for their papers.

If Princeton wants to get back into the fray, it’s a matter of

will, not chance, says Horowitz: “The only way they’re ever

going to [become a force] is if the people at Princeton wake up and say,

this is something that is important to us.” ![]()

Merrell Noden ’78 is a frequent PAW contributor.