|

|

January 25, 2006: Features

Architecture

New

designs

A hotbed of theory gains influence on the ground

By Fred A. Bernstein ’77

In October, Elizabeth Diller, one of Princeton’s best-known architecture professors (and a founder of the Manhattan firm Diller Scofidio + Renfro), received the National Design Award at New York’s Cooper-Hewitt Museum, in the category of architecture. “This is quite an honor,” Diller announced, “for a firm that has only recently added buildings to its repertoire.”

In the 15 years she has taught at Princeton, no one doubted the quality of Diller’s thinking — in 1999, she and her husband, Ricardo Scofidio, won a MacArthur “genius” grant for creating an “alternative form of architectural practice” in which installation art, electronic media, and performance were as important as building design. Their architecture-themed writings and contemporary art installations had been attracting attention for two decades. But suddenly, Diller and her partners have several large projects under construction (see page 48). In that sense, she is emblematic of Princeton’s architecture school, which itself is adding buildings to its repertoire. For the first time in a quarter-century, the school’s work is becoming, literally and figuratively, concrete.

For years, Princeton has been “the most theoretical program around,” observes Toshiko Mori, head of the architecture program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. Students learned to talk the talk of architectural theory — an approach that produced some important critical thinking on architecture. But it had less impact on what actually got built, and though Princeton has produced leaders in both teaching and practice, Dean Stanley Allen *88 acknowledges that in the past there was “a sense that [students] did not necessarily have the professional skills necessary to be competitive.”

To some, that’s an indictment of the architecture school. But Princeton has long eschewed professional education; until the 1960s, the school was closely affiliated with the department of art and archaeology. Robert Venturi ’47 *50, perhaps the most famous architect to graduate from Princeton, recalls that in the postwar years, when other schools were “in the process of erasing history,” Princeton was embracing it. And if that made Princeton anathema to the modernists at other Ivy League architecture schools — particularly at Bauhaus-influenced Harvard — it enabled Venturi to develop a style informed by classical precedent, which eventually caught on: Picture Princeton’s Renaissance-inspired marble-and-granite façade of Gordon Wu Hall (1983) or the patterned brick of the Lewis Thomas Laboratory (1985), both designed by Venturi and his wife and partner, Denise Scott Brown.

In the 1960s, the school began attracting young faculty with more concepts than clients. Among them was Michael Graves, whose approach involved the use of columns, decorative moldings, and classical pediments in surprising combinations and colors. For much of the 1970s, the school had the quality of a cult dedicated to Graves’ aesthetic, which existed largely on paper. But then, in 1980, Graves exploded into three dimensions with a municipal building in Portland, Ore., featuring historical motifs writ large. The building helped usher in a style called postmodernism, in which ornament was de rigueur. It was a heady moment for Princeton, when the ideas that had swirled around the architecture school found real-world applications.

Postmodernism, it turns out, was short-lived. But now, 25 years later, the school seems to be entering another crossover moment, when ideas hatched in the architecture building are turning up in bricks and mortar (or, more likely, aluminum and high-tech plastic). Several longtime faculty members, once considered full-time intellectuals, are

suddenly spending much of their time at construction sites. Among them are Diller and visiting professor Peter Eisenman, who at 70, has more than $1 billion worth of projects in the ground. Both Eisenman and Diller are extraordinarily influential among younger architects.

Allen, a New York architect who became dean in 2002, says Princeton’s shift is illustrative of the entire discipline’s turn away from theory — though not from intellectual rigor. Mainstream practice today, he says, recognizes “that the ability to think through complex problems in an intellectually sophisticated manner — which is the competitive advantage our students and faculty have — is, more and more, a necessary attribute to successful design practice.”

In the school’s master’s program, which has 56 students enrolled this year, Allen is working to reduce the emphasis on theory. “In the ’90s,” Allen says, “the school had these amazingly interesting people in history and theory, but not much design to go with it.” Now, he says, “we’re getting the students to draw more, to build models more, to be more engaged and more hands-on — not to treat design as a kind of afterthought.” But at the same time, Allen is shifting the undergraduate program, with 31 concentrators, to center less on design and to be more consistent with Princeton’s liberal arts emphasis. This move began even before Allen’s arrival, when the school began encouraging all seniors to do written theses instead of design projects (although the theses often incorporate drawings). “We want to do what the college does well, which is teach people in a broad liberal arts context,” he says. “What we don’t want to do is give undergraduates a watered-down professional education.”

The school’s design studios, where students toil day and night, have become less about aesthetics and more about technology. “We’ve found technical people who are used to collaborating with architects, and brought them into the studios,” he says. An example is Marc Simmons, an expert in the high-tech skins (called curtain walls) that cover commercial and institutional buildings. Thanks to Simmons, students, instead of thinking of a building envelope as a solid surface, are beginning to think of it as a “system” that controls light, temperature, and other building conditions, Allen explains. Allen has also recruited “digital assistants” — staff members who help students learn to use computer-aided design programs as they work on their studio projects. “The technical demands on the architects these days are huge,” Allen says.

Allen also has given the school a strong international focus — beyond the study of Greek and Roman architecture that influenced Graves and Venturi. The Japanese architects Kazuyo Sejima and Ryue Nishizawa (designing the New Museum for Contemporary Art in Manhattan) have joined the faculty as visiting professors and will teach a master’s

studio this spring. At the same time, longtime faculty member Mario Gandelsonas has devised a cooperative venture with an architecture school in China; Princeton students will collaborate with students in their Chinese counterparts on a project in Shenzen. Passports are now as necessary as pencils.

Allen is on an advisory committee that helps pick architects for campus projects, and says he is heartened by some of the recent choices, which bring architecture lessons home. The architecture school itself is about to begin a $2 million alteration that will make it ADA- and fire code-compliant, with an elevator placed in a new, transparent “link” that will replace the current lobby and main stairway. Allen says he hopes that students will benefit from watching the project unfold: “We make the argument that it’s a demonstration case of what a creative young architecture firm can do with a modest project under a strict budget and very tight constraints.”

The creative young firm in question — New York’s Architecture Research Office — was founded by Adam Yarinsky *87 and Steve Cassell ’86, who remember the days when the school was largely about theory. Fittingly, their link will help bridge the gap between the building’s two wings — student workspaces, where the focus is on drawing and model building; and faculty offices, where books and articles are the primary tools. That makes the link a physical manifestation of the school’s efforts to integrate thinking with doing.

The following pages show how some architecture faculty members are bridging theory and practice.

Stanley Allen

*88 |

Stanley Allen *88

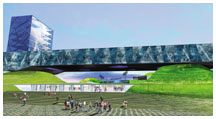

Even a leading architectural theorist can’t predict which way the profession is heading. But Stan Allen *88 does know that the days when clients came to architects with complete lists of requirements are over. Take Allen’s music center for the Taiwanese city of Taichung. Local officials knew they wanted an amphitheater and a concert hall. But Allen realized that the hall would be used only about 18 days a year. So he began investigating ways to “activate the site” with additional programs, such as galleries, a library, and “jamming garages” where local groups can come and practice.

Now Allen is involved in both winning planning approval and raising funds for the building, which, at 50,000 square feet, will be his largest completed project by far. The lengthy process helps explain Allen’s desire to ensure that students learn about more than architecture. Today’s architects, he says, “are typically engaged in the entire series of public processes — designing the building is only one small part of what we have to offer.”

A view of Stan Allen *88’s design for a contemporary music center in Taichung, in central Taiwan. The plan features an 18,000-seat amphitheater, a 400-seat concert hall, rehearsal facilities, and exhibition and education facilities that occupy a bridge – what Allen’s firm calls “a kind of horizontal skyscraper.” (courtesy Stanley Allen *88)

Paul Lewis *92 |

Paul Lewis *92

If anyone exemplifies Princeton’s move from theory to construction, it is Paul Lewis *92, an assistant professor of architecture who studied under Professor Elizabeth Diller and now employs half a dozen recent Princeton graduates in his Manhattan office. His firm, Lewis Tsurumaki Lewis (the other Lewis is his twin brother), recently completed a 47,500-square-foot dormitory at the College of Wooster in Ohio, after conducting a lengthy analysis of how students — who tend to work alone at computers — could be lured into more “social spaces.” The result, in part, was study carrels that face into a courtyard, like theatrical seating.

Now, while designing a museum in Austin and a spa in Las Vegas, the firm has completed four Manhattan restaurants, handling not just design but construction (assuming, Lewis jokes, that sticking 120,000 bamboo skewers into a restaurant ceiling qualifies as construction). Lewis says that’s very much in keeping with what he teaches at Princeton: “You don’t just design the building; you design the way the building will get built — a tactical approach to realizing a project.”

Above: Two views of Bornhuetter Hall, a dormitory at the College of Wooster. Before designing the building, Paul Lewis *92 studied how students could be lured into “social spaces.” The hallways and outdoor courtyard were designed to encourage social interaction. (Michael Moran)

Lewis’ firm designed the Xing Restaurant in New York City with four distinct areas, each marked by specific materials. For example, the front seating area is wrapped in bamboo, while the back dining area is defined by red velvet panels. (Michael Moran)

Elizabeth Diller |

Elizabeth Diller

If Michael Graves led the school’s postmodernist era, Elizabeth Diller, who joined the Princeton faculty in 1990, may be the leading light of its post-post-postmodernist phase. Her architecture, like orthodox modernism, eschews unnecessary ornament, but it tends to be whimsical and offbeat, straying far from the pure rationalism that was modernism’s raison d’être. Diller’s best-known creation (with partner Ricardo Scofidio) was the Blur Building, or The Cloud — a series of thousands of nozzles that created a cumulus formation over a Swiss lake. (Ephemeral, like most of the couple’s work to date, the structure was torn down after its six-month run in 2002.)

That same year, the firm won a competition to design Eyebeam, a media museum in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. Though the building was never constructed, the design, in which a single surface undulated to become walls, floors, and ceilings, spawned a generation of imitators. Last year, the couple was selected to lead the redesign of Lincoln Center — about as high-profile a project as any firm could hope for. Their plan includes peeling away parts of the skin of Alice Tully Hall, turning forbidding surfaces into tantalizing peeks at architecture’s underside. Also under construction is their new building for the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, which will cantilever over Boston Harbor. And their design for the High Line will turn lower Manhattan’s abandoned elevated railway into a linear park.

Above, the Blur Building in an artificial cloud at the base of Lake Neuchâtel in Switzerland. The structure was part of Swiss Expo 2002; visitors were meant to “experience a sense of physical suspension.” (images courtesy DILLER SCOFIDIO + RENFRO)

Right, a rendering of the new façade planned for Alice Tully Hall and the Juilliard School, part of a redesign, led by professor Elizabeth Diller’s firm, of cultural facilities at Manhattan’s Lincoln Center.

Guy Nordenson

|

Guy Nordenson

Master’s students who take “Introduction to Structures,” a course taught by Guy Nordenson, are in good hands: Nordenson has established himself as the engineer many top architects depend on to solve complex structural problems. (Among his current projects is a home for the art school at the University of Iowa, designed by Steven Holl; Nordenson had to figure out how to cantilever the building over a pond, on an extremely tight budget.) But working with architects on individual buildings is only one small part of Nordenson’s career, which he says mostly concerns “democracy.” Engineering, he explains, is largely about infrastructure (the delivery of water, electricity, and other services), and infrastructure, in turn, is about who makes decisions in a society.

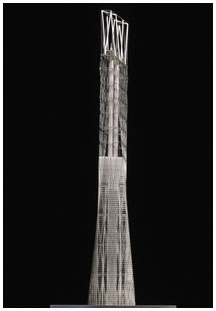

After 9/11, Nordenson helped design a 2,000-foot tower at the World Trade Center site with architect David Childs — a response, he says, to a Daniel Libeskind design that he found

“fascistic.” That design was altered at the direction of Gov. George Pataki, and Nordenson withdrew from the project. But last year he returned to Ground Zero, where he is designing the structure that will support the slurry wall, the section of the World Trade Center foundation that will remain on permanent display.

For all the machinations at Ground Zero, he says, he is relieved that “with so many constituencies, things move slowly, and, as a result, the decisions are pretty good. It ain’t Robert Moses,” he says, referring to New York’s ultimate power broker, who was anything but democratic.

Princeton professor Guy Nordenson worked on this design for a 2,000-foot tower at the World Trade Center. The design was altered to become the 1,776-foot-tall Freedom Tower, and Nordenson withdrew from the project. (courtesy Guy Nordenson)

![]()

Fred A. Bernstein ’77, who majored in architecture, writes about the topic for The New York Times and other publications.