April 2, 2008: Books and Arts

Reading Room

A world traveler

Linda Colley uncovers the atypical life of an Englishwoman

From chamber music to multimedia

installations

Young composers find their own sounds at Princeton

Gilbert Levine ’71 brings ‘Missa Solemnis’ to public television

For a complete list of books received, click here.

Professor

of history Linda Colley explores the restless life of Elizabeth Marsh

and how it reflected the increasingly interconnected, global world

of the 18th century. (© Niall McDiarmid, courtesy Pantheon &

Schocken Books) Professor

of history Linda Colley explores the restless life of Elizabeth Marsh

and how it reflected the increasingly interconnected, global world

of the 18th century. (© Niall McDiarmid, courtesy Pantheon &

Schocken Books) |

Reading

Room

A

world traveler

Linda Colley uncovers the atypical life of an Englishwoman

By Deborah Yaffe

The contact had been made in the modern way, via e-mail. Princeton history professor Linda Colley had found a genealogical Web site whose creator had offered to show her a cache of family documents about her latest research subject, an obscure 18th- century Englishwoman named Elizabeth Marsh.

But when her cab pulled up outside a small house deep in the English countryside, Colley suddenly was struck by Hitchcockian overtones. “Nobody knows I’m here,” she thought. “I don’t know this man.”

Fortunately,

her host was no Norman Bates — just a family-history buff who had

filled an entire floor of his house with centuries-old documents, some

offering irreplaceable insights into the background of Marsh, an ancestor.

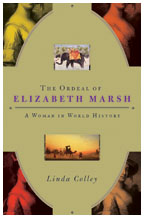

Colley’s book, The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A Woman in World

History, was published last summer by Pantheon; The New York Times

named it one of the 10 best books of 2007.

Fortunately,

her host was no Norman Bates — just a family-history buff who had

filled an entire floor of his house with centuries-old documents, some

offering irreplaceable insights into the background of Marsh, an ancestor.

Colley’s book, The Ordeal of Elizabeth Marsh: A Woman in World

History, was published last summer by Pantheon; The New York Times

named it one of the 10 best books of 2007.

Colley, who specializes in 18th-century British history, first discovered Elizabeth Marsh while researching a previous book, Captives, which tells the stories of Britons kidnapped overseas as their country built its worldwide empire from 1600 to 1850.

Marsh was one of them: In 1756, at the age of 20, she was fleeing a feared French attack on Gibraltar when her ship was commandeered by North African corsairs in the Mediterranean. Taken to Morocco, she crossed the desert on mule-back, met the acting sultan, declined to join his harem, and eventually was permitted to return home. The captivity narrative Marsh wrote years later became the first English book about Morocco written by a woman.

Colley, who retraced Marsh’s journey through the Moroccan desert, initially planned to turn this “rattling good story” into a quick little book. But as she delved deeper into Marsh’s restless, eventful life, Colley came to see it as something more emblematic — “a global story ... a world in a life and a life in a world,” as she would eventually write.

Marsh was conceived in Jamaica, where her British father worked as a shipwright, and was born in England in 1735. Over the next 49 years, Marsh lived in British outposts in the Mediterranean, married an up-and-coming merchant with commercial ties to Asia, Africa, and the Americas, and moved with him to India after bankruptcy forced him to start afresh as an employee of the colonialist East India Company. Later, though still married, she spent 19 months traveling around the Indian subcontinent with a man she described ambiguously as her “cousin.”

In the rapidly changing, increasingly interconnected world of the 18th century, Marsh’s unusually adventurous life was shaped by war, migration, slavery, global trade, naval power, and empire building. Marsh’s experience was atypical not because she was touched by key developments, notes Colley, but because she was touched by so many of them.

“It’s important to show the linkages between these great

global shifts and the intimate structures of human lives and families,”

Colley says. “Because, after all, this is something that we experience

ourselves today — the impact of globalization can affect ordinary

lives.” ![]()

Deborah Yaffe is a writer in Princeton Junction, N.J.

For a complete list of books received, click here.

X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft But Can Still Keep Everything

From Sucking — Jeff Gordinier ’88 (Viking). In this

witty book the author argues that those born between 1960 and 1977 —

Generation X — quietly have changed American culture by influencing

art, comedy, technology, activism, and business. Though marginalized and

accused of being slackers, Gordinier’s generational comrades, he

writes, are responsible for YouTube, Google, and The Colbert Report. Gordinier

is the editor-at-large at Details magazine.

X Saves the World: How Generation X Got the Shaft But Can Still Keep Everything

From Sucking — Jeff Gordinier ’88 (Viking). In this

witty book the author argues that those born between 1960 and 1977 —

Generation X — quietly have changed American culture by influencing

art, comedy, technology, activism, and business. Though marginalized and

accused of being slackers, Gordinier’s generational comrades, he

writes, are responsible for YouTube, Google, and The Colbert Report. Gordinier

is the editor-at-large at Details magazine.

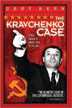

The Kravchenko Case: One Man’s War on Stalin —

Gary Kern *69 (Enigma Books). Based on documents obtained under the Freedom

of Information Act and interviews with the defector’s sons and associates,

this biography explores the life of Soviet defector Victor Kravchenko,

who emigrated to America in 1943, and his role in the Cold War. Kern also

wrote A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror.

The Kravchenko Case: One Man’s War on Stalin —

Gary Kern *69 (Enigma Books). Based on documents obtained under the Freedom

of Information Act and interviews with the defector’s sons and associates,

this biography explores the life of Soviet defector Victor Kravchenko,

who emigrated to America in 1943, and his role in the Cold War. Kern also

wrote A Death in Washington: Walter G. Krivitsky and the Stalin Terror.

Embryo: A Defense of Human Life — Robert P. George

and Christopher Tollefsen (Doubleday). Saying they put forth a scientific

and philosophical argument, not a religious one, the authors maintain

that the fetus, from the moment of conception, is a human being, and therefore

due moral and political rights. As a result, they argue, society should

not condone or publicly fund embryonic stem-cell research. George is a

professor of jurisprudence and director of the James Madison Program at

Princeton. Tollefsen is an associate professor of philosophy at the University

of South Carolina. ![]()

By K.F.G.

David T. Little

Seth Cluett

Betsey Biggs (photos, from top: Bender Photography, courtesy David T. Little GS; courtesy Seth Cluett GS; courtesy Betsey Biggs GS) |

From

chamber music to multimedia installations

Young composers find their own sounds at Princeton

By Alicia Brooks Waltman

When graduate students in Princeton’s music-composition program compose, one might sit down at a piano, while another taps on a laptop computer. Yet another grabs a microphone and video camera to capture the sounds and images of everyday life and present them as art.

Doing pieces on subjects ranging from the political to the whimsical to the everyday, there is no single sound among the works of the program’s 26 students, whose compositions include chamber music, pieces for laptop computers, and multimedia, installation art using objects and sound.

Accepting just four new Ph.D. candidates each year from a pool of up to 100, the program is highly competitive and in the top 10 around the country, says associate music professor and director of graduate studies Barbara White. Though it’s small, it’s diverse, attracting students who have degrees and careers in areas outside of music as well as those who have composed professionally, with students ranging in age from their 20s to their 40s. There is no core curriculum; course offerings change each semester, depending on faculty and student interest. And professors don’t set out to hone any one sound in their students. “We’re known as pluralistic and open to all sorts of styles,” says White.

Take the work of David T. Little. At 29, in his fourth year at Princeton, he’s already written more than 50 compositions — orchestral music, percussion solos, and music for Newspeak, a group he founded in 2001 that specializes in political and socially oriented music.

Little is at work on a dissertation on political music, specifically music used in revolutions. His recent work, Soldier Songs, is an hour-long theater piece featuring strings, clarinet, and piano that incorporates dialogue from veterans, among them a soldier describing what it’s like to run from incoming missiles. (It will be presented by the New York City Opera on May 11 and in Houston on May 29.)

“I wasn’t trying to make a statement about war, so much as letting the soldiers tell their stories,” says Little, who with fellow Princeton graduate student Judd Greenstein has formed a collective of composers called Free Speech Zone, which produces politically themed music.

Third-year student Seth Cluett’s work looks at a different revolution: that of how we listen to music. Cluett’s dissertation is a “social and artistic investigation of the loudspeaker,” exploring the idea that, as fewer people attend concert halls to hear music, “home studios and headphones are becoming a venue,” he says.

Cluett, 31, who has a master’s degree in electronic art from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, composes works using computerized sound, photography, video, and live performance, to name just a few elements. He’s also co-director of PLOrk, the Princeton Laptop Orchestra.

Sixth-year student Betsey Biggs, 42, who writes music employing instruments, vocals, electronics, and visual art, wants her works “to resonate memory” among her listeners.

“Sound is uniquely powerful at bringing up memories we didn’t know we had, in a pristine way,” says Biggs. With this in mind, she is working on a series called “Park Bench Cinema.” The first installment, performed last fall at the Conflux Festival in Brooklyn, was a city soundscape that festival-goers downloaded to their MP3 players. Meeting during the festival on a street in Brooklyn, they turned on the players and took a 25-minute walk to the East River, listening to Biggs’ recording of sounds of the area combined with instrumentation.

“I’m interested in getting people to listen to their environment more and see wonder and beauty in little, strange gestures,” says Biggs.

The composers say Princeton is a fantastic place to practice their craft. The complete academic freedom, says Little, has been exhilarating.

“You’re here to become your own artist, that’s what’s

valued at this place,” he says. “It can be hard — you’re

out in the desert, and you have to find your own way. But when you do,

it’s so rewarding.” ![]()

Alicia Brooks Waltman is a writer in Hopewell, N.J.

Gilbert Levine ’71 screened his latest PBS program, which airs this month, at Princeton. (Courtesy Gilbert Levine ’71) |

Gilbert Levine ’71 brings ‘Missa Solemnis’ to public television

It took Beethoven four years to compose what he considered one of his greatest works, Missa Solemnis, a setting for the Catholic Latin mass. But he never witnessed the performance of the entire work, and the premiere of three of the five movements occurred in a concert hall, not a church, as he had intended. But thanks to conductor Gilbert Levine ’71, Beethoven’s complete work debuted in the magnificent Cologne Cathedral, a place that Beethoven himself knew well, having grown up in nearby Bonn, Germany.

In 2005, Levine conducted the Missa Solemnis in Cologne Cathedral with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, the London Philharmonic Choir, and four soloists; he produced a program of that concert that will air on PBS in the Philadelphia, New York, and Washington, D.C., regions on April 13 to coincide with Pope Benedict’s first visit to the United States. (It will air in other regions on different dates beginning April 6.) In late February Levine screened the PBS program, From Heart to Heart: Beethoven’s Plea for Peace (the title is based on the composer’s notations on his manuscript), in Fine Hall’s Taplin Auditorium. The program includes a recording of the Cologne concert and close-ups of the cathedral’s stained glass and artwork — corresponding to sections of the mass — as well as panoramic views of the inside and outside of the building. As an introduction, Levine gives a brief overview of Beethoven and the Missa Solemnis, and Pope Benedict describes the spiritual underpinnings of the work.

Levine, who has conducted orchestras around the world, including the New York Philharmonic, the London Philharmonic, and the Hamburg Philharmonic, has produced six other concert-documentaries for PBS. “There are very few concerts on public television,” says Levine. “Ours have succeeded because we give the viewer enough historical information, but not too much. We don’t want to detract from the musical experience itself.”

Levine’s long friendship with Benedict’s predecessor, Pope

John Paul II, who knighted Levine in 1994, has helped the conductor approach

the work of Beethoven and other composers “in a deeper way,”

he says. He first met the pope in 1987, soon after Levine had taken over

as artistic director and principal conductor of the Krakow Philharmonic,

and later he performed at the pope’s 10th anniversary, at the Papal

Concert to Commemorate the Holocaust, and at the Papal Concert of Reconciliation.

The pope, said Levine, who is Jewish, believed music could “bring

people of different faiths together.” As a result of that friendship,

Levine says, he looks to better understand composers’ spiritual

lives. Without that friendship, he says, “I wouldn’t have

had the spiritual tools to understand Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis.”

![]()

By K.F.G.

|

(Frank Wojciechowski) |

Katie Wong ’10, left, and Elizabeth Schwall ’09, photographed during a rehearsal, and 16 other students performed choreographer Susan Marshall’s “Name by Name” at the Spring Dance Festival held Feb. 22 through 24 at the Berlind Theatre in the McCarter Theatre Center. The dance evokes the driving strength of women overcoming tradition and creating their own identity. The annual festival, produced by the Program in Theater and Dance and directed by program founder Ze’eva Cohen, features student dancers and choreographers who have worked with faculty members, guest choreographers, and professional artists during the fall semester.