|

January 26, 1965 Princeton Portraits: Bill Bradley '65

By Frank Deford '61

This acute portrait is by the skillful hand of Frank Deford, former PAW sports and "On The Campus" columnist, now a staff writer on 'Sports Illustrated,' where it appeared in December -- before the Madison Square Garden tournament in which Bill Bradley won the Most Valuable Player award (and before the announcement of his Rhodes Scholarship). It is reprinted by permission (c) Time Inc. 1964. The photographs show him at Chung Chi University at Hong Kong, where he was sent (also Tung Hai University on Taiwan) after the Olympics by the Princeton in Asia Foundation which helps support them. There he conducted basketball clinics and spoke to the students about the relation between athletics and Christian beliefs; according to this week's 'New Yorker' profile, "religion is his central source of motivation," and he told his hosts he valued this fascinating missionary trip more than the Olympics.-ED.

|

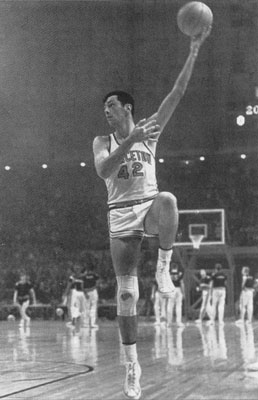

Bill Bradley '65 takes a hook shot

|

IF YOU look at all of him squarely, Bill Bradley seems too good-and too much-to be true. He is the best college basketball player in the world (he won an Olympic gold medal and was the best on the U.S. team in Tokyo); he is studious, religious, ambitious, popular and respected by his peers; he is trustworthy, loyal, helpful, courteous -- he is, in short, Jack Armstrong and might also be Horatio Alger, except for the fact that his father is a bank president and is paying for Bill's room, board and tuition at Princeton.

Fortunately -- you have to look hard for a flaw -- the quirk of a permanently arched left eyebrow gives him a mischievous, almost Satanic, appearance, but that, too, is quickly disputed by the sober, purposeful eyes, far more accurate gauges of this young man's personality. Bradley is dark, angularly strong, with a few more than 200 pounds on a lithe 6-foot-5 frame. His smile truly reflects his warmth, though he can hardly be called the happy-go-lucky type. But it does belie his rigorous determination and self-discipline. Bradley insists that he is not a natural athlete. Without detracting from the immense effort he has put into basketball, few observers would agree with this estimate. It probably is true that his more modest academic success is the result of hard work rather than natural aptitude. Any Princeton student will tell you that a man who studies as much as Bradley does should be better than a B student -- even if that would be A at most other schools.

Despite the fact that Bradley and Princeton get along marvelously, there is still mild astonishment that the best player in the country should be matriculating at Old Nassau, an institution which has produced twice as many presidents as basketball All-Americas, i.e., James Madison, Woodrow Wilson and William Warren Bradley. But there are certainly no regrets on Bradley's part about his choice of college. He picked Princeton in the 11th hour, leaving Duke at the very altar and about 60 other schools and their coaches on the road to the church. All had been attracted by a high school career in Crystal City, Mo.. that included 3,066 points and two years of prep All-America. One of the losing coaches said sourly that Bradley could have been the greatest college player ever, but performing in the relative obscurity of the Ivy League would deprive him of that chance.

It has worked out, of course, in reverse. The novelty of having such an athlete performing in the shadows of ivy-walled Nassau Hall -- without a grant-in-aid, without ersatz courses of study -- has only enhanced Bradley's reputation. In the unique setting of the Olympic trials, where all of the best amateur players are thrown against each other in direct competition, without the support of familiar teammates, Bradley was the only undergraduate selected. Further, he had to make the team as a guard, after playing almost exclusively as a forward for Princeton, because the coaches thought he was too small for the forecourt in this competition. When they discovered they were wrong, he went back to forward and became the most valuable player on the winning U.S. team.

At Princeton, Bradley blends in easily though, basketball aside, he is still not a typical undergraduate -- he is more serious and less blasé than most. He plays basketball with an air of nonchalance, however, and is treated with roughly that attitude on campus. This delights him. He enjoys contrasting his reception after the Olympics with the full-blown parade that the town of Princeton gave its gold-medal winner, Diver Lesley Bush. "I flew back," he says, "and took a bus from New York and finally got to Princeton about 9 one morning. Thirty straight hours of travel. There was nobody to meet me. I just walked down to my room. A few people said hello or welcome back, but that was about it."

Actually, Princeton does take a prideful interest in its All-America -- in its own fashion -- and Bradley has had something of a lasting effect on the school. When he arrived, games at snug little Dillon Gym (2,600 rollout seats) were characterized by the atmosphere of a public hanging. Students showed up mostly to take out their wintertime frustrations on opponents. On one notable weekend the visiting Harvard captain was driven into fighting with some of his tormentors on Friday night, and on Saturday night the Dartmouth players were pelted with rubber-band-propelled paper clips. [The offending individual was promptly expelled.-ED.] An appeal by the coach and captain during Bradley's sophomore year helped, but it was more his regal presence on the floor that finally brought an urbane attitude to basketball watching. "It's like -- well, I don't think you could chuck garbage at anyone on stage when Caruso's up there too," an undergraduate explains.

Sellouts at Dillon were common enough, but after Bradley started playing, basketball seating had to be restricted on the same basis as football. About 440 extra (and bad) seats will be crammed in this year, but still only students, faculty, a few alumni and opponents will be able to get in. It is no coincidence that Princeton has finally become serious about building a much larger indoor athletic complex. Plans are being speeded for a new arena that will seat upward of 7,000.

Prodigious Purpose

But Princeton students hold Bradley's basketball skill less in awe than they do his prodigious purpose. He studies in virtually all of his free time and seldom gets more than six hours' sleep. Before one game last winter, when he was completing an important history department paper on nativism in the U.S. after World War I, he trained with four straight nights of about two hours' sleep each. His teammates say that he plays so well on the road simply because travel keeps him away from Firestone Library and obliges him to sleep more. Two hours before every home game he goes back to his room in Dodge-Osborn Hall and is able to drift right off for a 40-minute nap. "Well, you know, I'm so tired, it's not hard," he says. He is so conscientious that he has been known to ask roommates to wake him up from a nap at, say, 5:27 instead of 5:30. To save other minutes he takes many of his meals at the student union, which is several hundred yards closer to the library than his eating club, Cottage.

Bradley lives -- after the library closes at midnight -- with five roommates. The only other basketball player among them, Bill Kingston, is perhaps as close to him as anyone. "Getting to know Bill has been worth the four years here," Kingston says. "But always, I just wish he could be more outgoing." Donald Mathews, a young instructor who was Bradley's advisor last year and became a friend as much as a teacher, says: "He comes to generalizations painfully. I think Bill is becoming more mellow, but he will never shoot the breeze, as it were, without having done some studying on the subject."

Bradley is restrained intentionally because of the special pressures upon him -- he says things like, "No one has to know my motives," and "I don't have to wear my heart on my sleeve" -- but he is also naturally reticent. "Of course," teammate Ed Steube says, "it would be nice to have Bill loosen up, but then you see, it wouldn't be Bill Bradley."

Bradley does find the time for an occasional party, to stomp out a little rock 'n' roll and to see some musical comedies. He is socially popular, not through wit or special grace, but because he is genuinely interested in others. Conversely, the vast amount of public interest in Bill Bradley often confuses and disconcerts him, especially the talk that he "made good on his own" despite family affluence. Filling out Princeton's standard athletic forms in his freshman year, he identified his father as "banker." On the same form, as a sophomore, he changed that to read "works in bank." As a junior, he just left the "Parent's Occupation" entry blank.

Bradley toured Europe after his senior year in high school, so he was not exactly fresh off the Midwest front porch when he arrived at Princeton. He is not naive about the challenges he faces, but neither have his schoolboy precepts been altered very much. In his room at Princeton a few days ago, he said: "If the time ever comes when I can't cry sometimes or can't jump up and down and get really excited or get moved to the point of chills, then I've changed and I'll know it. But just because I am an All-America, that doesn't mean my opinions have changed. I hope I have matured but -- and I don't mean this literally, of course; not out of context -- but I guess I'm still the same boy from a small town in Missouri."

Coming from a small town named Crystal City seems almost too perfect for an All-America, and the fact that Bradley is not already being called the Crystal City Kid or something similar is a pretty good indication that he is not colorful. He sure isn't. And because he is so uniformly excellent that no facet of his game stands out, it is even difficult at first to tell how good he is on the court. In high school and at Princeton for instance, he has had to be the big shooter, and he has averaged 30 points per game in college. Yet when he played an exhibition game against Baltimore with the Olympic team, the Bullets' Bailey Howell qualified his praise to say: "He didn't seem to even look for shots." Only once -- when he scored 51 against Dartmouth last winter -- has he ever deliberately tried to push his own point total. He had tied his Ivy record of 49 in the game, and the fans cried for more. "I just took three shots to make two points," he says, "so I could get out of there." It is a good guess that he will not score as much this year for Princeton, since the team has picked up more talent.

On the Olympic team, where scorers abounded he was content to be more of a playmaker, though with his diverse skills he was actually an all-court catalyst, sparking, every phase of team play. Significantly, he played much more than any other American. "He just seems to know what to do, when to do it and how to get it done," says Alex Hannum, the San Francisco Warrior coach.

Bradley was the only U.S. player smart and flexible enough to convert his style to take advantage of the international rules, which so favor an aggressive offense. He drew many more fouls than his teammates by driving far more than he normally does. And his foul-shooting is already legendary; once he hit 58 in a row. With meticulous practice he has developed just about every shot. He can hook as well as jumpshoot or drive. He is equally adept at going to his left or right and shoots with either hand. Cincinnati Royal Coach Jack McMahon recalls when Bradley was a high school junior: "He went to Ed Macauley's basketball camp. He had hurt his right arm, but he went down there anyway, and Ed said, 'Just practice with your left hand.' So he hit nine of 10 free throws lefthanded."

Bradley is not a spectacular jumper, but he gets good position. He is not exceptionally fast either, but he has quick hands, and when he gets loose on a break, his loping, cutting strides make him appear as fast as anyone. He can improve his accuracy from a distance, and he probably will if he decides to turn pro. At Princeton, his dedication to scholarship has restricted his basketball practice, but he has been almost fanatically faithful to the game ever since he was reprimanded for missing a session when he was 12 years old. This was hardly the result of even minor delinquency, however -- he had passed up the practice for a boy scout meeting. (Similarly, the story goes, the only time he was heard to curse was when he muttered "damn it" as he rushed from his room -- late to teach Sunday school.)

But of all his accomplishments, it is most typical that Bradley has now vastly improved the two elements of his game once considered weakest. Princeton Coach Bill van Breda Kolff noted immediately upon his star's return from Japan that he was much better off the boards -- "He's no longer an Ivy League rebounder." Some observers have insisted that he has not sufficiently aggressive overall: but the pros he played against as an Olympian do not agree. "When he puts a block on you, he lets you know it," says Tom Hawkins of the Royals.

Even more significant is Bradley's spectacular improvement on defense. When he came to Princeton he was like many high school stars whose coaches have shielded them from heavy defensive chores in order to keep them out of foul trouble. Van Breda Kolff schooled him thoroughly and made him guard the opponents' toughest men. Jack McMahon says, "I knew about Bradley's offense, and I knew his versatility. I know at Princeton he has to score. But what impressed me when he played against the Royals was that he was so aggressive on defense." The highest accolade of all, however, comes from Hank Iba, the Olympic coach who is a fanatic on this aspect of the game. He names Bradley as the U.S. team's best defender.

A Complete Player

Bradley is, then, a complete player. And a winner, too. He has led Princeton to two Ivy titles, and this year the Tigers should breeze to a third. He has already gathered in every honor this side of Miss Teenage America. His own highest sports goal was to make the Olympics, and having played so magnificently in Tokyo, he may indeed find it difficult to be stimulated in his last college season. As a pro, though, Bradley would have much more of a challenge than just living up to his reputation. At his height, in the NBA, he is pegged as too small for a forward, and too big -- or, rather, too slow -- for a guard. Says Ed Macauley, a St. Louisan who has known Bradley since high school, "I think Bill will have to be a guard in the pros and if he is, he will have to make a major adjustment. He can do everything -- shoot, pass, dribble and play defense. But until he does make the adjustment in style there must be at least some reservations about him."

Harry Gallatin. on the other hand, has hardly any doubts about Bradley's future. The St. Louis Hawks coach feels that he can star as a swing man, playing the way John Havlicek has done. "Bill probably will spend a majority of his time as a guard and he will have his problems" Gallatin says, "but his assets will more than make up for any trouble he might have with the smaller backcourt men."

Speculation about Bradley's ability to play pro basketball is, however, somewhat moot. He is not so sure that he will try it. "If I wanted to prove myself and I knew I had the desire to continue, I'm sure I would," he says. "But right now, there are too many alternatives. I don't need basketball competition. The attitude is what is important, and I've gotten that out of the game already. I love the game. It's part of me. I don't think, how ever, that it's an inseparable -- there ought to be a better word -- oh, well, an inseparable part of me. At one time I thought I couldn't live unless l played baseball, and I gave that up."

Bradley is considering six alternatives to the pros. Some of them are admitted smoke screens -- "I say some of this to confuse people; it's still my business" -- but he is obviously interested in both law school and study abroad. The other possibilities are the ministry, government work, business and the Air Force. His future is likely to remain indefinite for a while because Bradley, right now, is more concerned with the present, and particularly with his thesis, which is a major part of a Princeton senior's grade. His topic is "The 1940 Senatorial Campaign in Missouri," and he did a great deal of work on it over the summer at the Library of Congress when he was in Washington. (He split the rest of his time between helping in Governor Scranton's campaign and practicing for the Olympics.) Bradley has personally interviewed one of the losers of that 1940 campaign and hopes to meet with the winner when he gets a Christmas break from basketball. The winner maintains a library in Independence, Mo. Bradley is also an eager public speaker -- he virtually solicits engagements from youth groups -- and because of his forensic aptitude and his qualities of leadership, it has been suggested that he already has his dark eyes on that Senate seat he is now writing about.

One usually levelheaded New York journalist has asked Bradley -- seriously -- if he would like to be President. Bill dismisses such talk as foolishness and insists it would be presumptuous even to answer the question. But they are going to be writing about this young man for years to come -- and not just about the way he dribbles a basketball.

"He is a Christian the best way he can be, through the rigors of Calvinism." Donald Mathews says, trying to explain him. "He's never going to lose. Bill is always going to come back. Do you know?" He smiled and paused. "Do you know just how hard it is to defeat a 16th century Puritan?"