By George H. Harmon '63

Willem H. (Bill) Van Breda Kolff '45 is a frank and good-humored man, universally liked by all who know him personally. But lately he has been something of a punching bag here in central New Jersey.

After coaching only 12 games, Van Breda Kolff is coping with more pressure than the normal basketball coach has to face in 12 years. Among the punches he is presently dodging: the bother raised over super-star Bill Bradley; a blunt and bloodthirsty home crowd; a team which was given too much publicity too early and consequently came to be overrated in the eyes of its followers; and overt criticism from alumni and students. These jabs, however, have had no more effect on the coach than jabs on an everlast inflatable.

Nor is there much solution to the overrated state of Princeton basketball. The team supported its advance publicity by getting off to an unusually good start, winning its first six games and moving from a dark horse position to sole favorite for the Ivy title. Voices thus began to be raised when it lost two contests (Yale and Pitt) that it shouldn't have. Criticism consequently showered on Van Breda Kolff from the stands, in the morning mail and behind his back. So far, he has allowed it to roll off him like droplets of water.

There is no solution to the problem of Bradley -- he will be hounded by newsmen until the day he graduates. There are only a few magazines and newspapers (National Geographic, The Village Voice, etc.) which have not treated the sophomore in an article. (A bit later than most, Life and Newsweek just finished gathering their information last week.)

January 18, 1963

Winter Sports: A Coach Under Fire

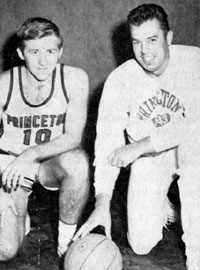

Van Breda Kolff (right)

and team captain Art Hyland

With his usual sprinkling of Anglo-Saxon adjectives, he added, "I enjoyed the boys in gym class last fall. I hate to see nice kids turn out like that." For an example, those "nice kids" were out in full force Friday night as the Tigers lost to Yale by one point. As usual they singled out one opposing player and berated his physical characteristics, adding a new twist in the final minutes by throwing wads of paper on the court. One referee was nearly hit by a large iron screw.

A Coach Under Fire

Van Breda Kolff is likewise powerless to do anything about the second traditional problem faced by the college coach: personal criticism. There are unsigned letters that inform him that he is a rotten coach. There are acid comments which reach him second and third-hand. There are well-wishing alumni who calmly tell him when to substitute and how to set up a fast break.

He and hockey tutor Norm Wood, seated at a desk across the room, worded the coach's dilemma in the same way: "If you win no one says a word, if you lose you get a lot of help." They emphasized that there are many mediocre coaches with consistent winning records, and vice-versa. The difference is really in the players. "I know a guy," said Van Breda Kolff, "whose high school team had a 9-0 record and the Jewish league team he coached at night was 1-8."

To illustrate the way he feels about "helpful hints" from the sidelines, Van Breda Kolff told a parable about Frankie Frisch and his managing days with the old New York Giants which went about like this: Frisch would coach third base, and each day a fan in the Polo Grounds grandstand would tell him, very loudly, how to run the team. Frank never said anything, but he had someone find out the fan's name. One morning when the fan appeared at work, he found Frisch seated beside his desk. Frisch stayed there all day, telling him what phone calls to make, what orders to write and when to expedite.

This is the way Van Breda Kolff looks at his job. It is a vocation ("I don't know what else I would do") and he doesn't want advice any more than Annual Giving needs pointers from him.

What has he accomplished within this context of pressure in the few months he has been here? Quite a bit. Most important of all, he has built a strong feeling of loyalty among the team members, loyalty both to one another and to the coach. He has accomplished it with an explosive but warm personality accompanied by a native ability to understand other people. Through the years-as a Princeton player, Marine, New York Knickerbocker, coach at Lafayette and Hofstra-''Butch'' has gained an extensive knowledge of a basketball player's temperament. "You have to be somewhat of a kid at heart, and know how you would like to be treated," he says.

He treats them firmly. His opening remark at the first preseason meeting was: "we will play by my rules." There is no monkey business, and yet he breaks into roaring laughter when a funny incident occurs, no matter how great the tension at the time. He is like the uncle who used to take you fishing when you were little and always understood you better than anyone else. The players thrive under such a personality. Said captain Art Hyland, with his characteristic economy of words, "He's really great."

And if the players are impressed by him, Van Breda Kolff is just as favorably impressed by them. He describes his team as "pleasant" and "intelligent." He smiled and added, "I've been waiting to say 'how can you guys be so smart in class and so dumb on the court?' but I haven't said it yet. They learn stuff awfully fast."

Speaking generally, he thinks Princeton students are more serious, with much less time for frivolity than in the 1940's. "Maybe it was because it was after the war, but the students always used to do crazy things. If you dropped into the 'Nass' on a week night, the place would be filled with guys, drinking beer out of pitchers and throwing glasses around," he remembered. Now, he says, all you see are businessmen and a few scattered undergraduates. The students these days seem a bit more withdrawn and "maybe that is why they let loose at the games." he said.

But during a game, he himself does a bit of letting loose, for then Van Breda Kolff is no longer quiet and analytical. He chews gum violently, leaps in the air and changes from his usual affable self into a man with a mania for vicarious game participation. He has no qualms about shouting at the referees when a violation is missed, just as he has no qualms about being outspoken on any subject. So far this year, he has had two technical fouls called against him, but in the quiet of his office he will tell you that he thinks the technical ought to be used more often against coaches. However, at a moment's notice. he can stop his sideline ravings and turn into a calm tactician.

Against Yale and Brown last weekend, his conduct was normal. He talked the whole time, sometimes to |\r coach Warren Harris, sometimes to no one at all. He did some loud talking to the referees, mostly about Yale men doing work with their elbows: "they're shovin' their way underneath . . . aren't you going to call anything under there? . . . doesn't that whistle work, Lou?" During one timeout, he grabbed a towel from one of his players and spent the period drying himself off. Such violent action sometimes provokes the crowd. But

Van Breda Kolff is calm when he needs to be, and once he called Hyland over for a quiet dressing-down after the captain got a little too rough. With two seconds left in the Yale game, he ran to the scorer's table and rattled the timekeeper's eardrums. Then he went back and casually set up a court-length play to give Bradley a final shot at the hoop.

Van Breda Kolff's enthusiasm has been exceeded only by his success. His record was 204-77 at Lafayette and Hofstra and in 1955 he was named Coach of the Year by the New York Metropolitan writers. In 1960 he had the No. 1 small college team in the nation with a 23-1 season at Hofstra. All of it has been done with a tight, man-to-man defense and a fastbreaking offense that he describes as "organized confusion." The method seems to work.