|

Web Exclusives: Bonus Stories November 6, 2002: An opinion

With

all of the new construction occurring on campus, I knew that Princeton

would one day seem very different to me. I just didn’t expect

this to happen so soon. In mid-September, I read the final report

of the Four-Year College Program Planning Committee — the group

responsible for developing the social, dining, residential and educational

objectives for Whitman College and the other two planned four-year

residential colleges. At first, many of the ideas in the programming

committee’s report impressed me. But then I realized that the

Princeton described in the report was not the Princeton that I knew.

It

is truly unfortunate that the programming committee’s report

failed to engage this question. I’m otherwise enthusiastic

about the report’s goal of diversifying social options and

encouraging normative changes that will enable the viability of

new opportunities. However, I can’t understand why the report

articulated these visions in a vacuum. By not discussing the opportunities

and obstacles represented by the eating clubs, the report neglected

to grapple with the realities of campus social life in formulating

the four-year residential college system. I keep asking myself if

this was an effort to avoid controversy, or if the university has

a hidden agenda. Here’s

a doomsday scenario. Upon the opening of the four-year colleges,

many upperclassmen elect the four-year residency plan because of

its affordability compared to the high cost of eating club membership.

At the same time, the institution of a flexible dining plan makes

it easier for upperclassmen to choose independent status. These

two factors will likely lead to decreases in club membership. Lagging

club enrollment accompanied by rising cost of facility maintenance

and need for capital improvements could pose serious financial constraints

for the clubs and force some of them to close. As it has done in

the past, the university will purchase these defunct clubhouses

and convert them to academic or non-social functions. The remaining

clubs may be forced to raise membership fees to stay afloat. Inflated

club membership fees and fewer clubs to choose from could lead to

a socio-economic rift on campus between club members and independent

or four-year residential college students. This situation would

exacerbate existing racial and ethnic divisions on campus. But yet,

since the new four year college system will not offer alternative

venues for large groups of people to socialize, listen to live music,

dance, or drink, much of the student body will still migrate to

the street each weekend for entertainment. Consequently, the eating

clubs will subsidize the social life—and alcohol consumption—of

a student body that has grown by 500 students, even while enrollment

at the clubs is on the decline. To avoid financial ruin, the clubs

might cease to allow entrance to non-members, thereby intensifying

exclusivity at the street and severely limiting social options for

students who don’t join clubs. In the meantime, Princeton Borough

will intensify its use of public pressure and legal means to end

nightlife at the street. With this type of pressure on the eating

club system, a meltdown of some sort is inevitable.

Far

more favorable scenarios for the future of campus social life are

possible. I know this because students envisioned these scenarios.

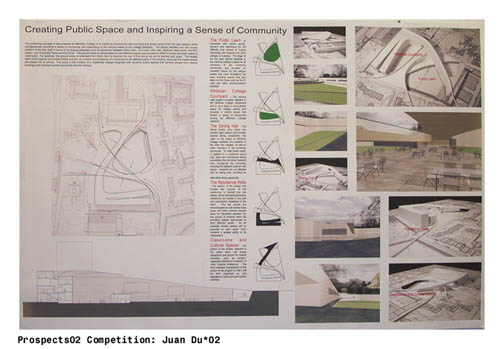

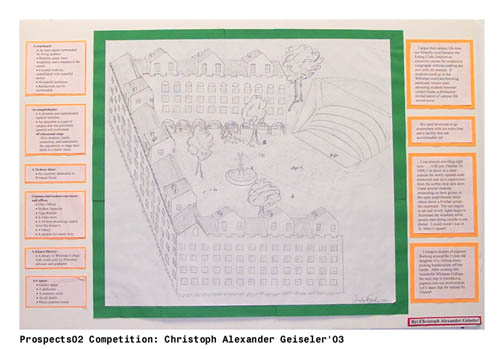

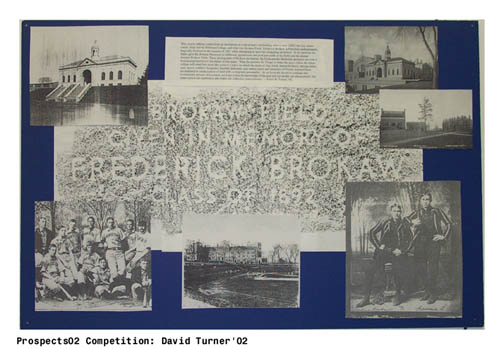

During my senior year I was a part of a student group called Prospects

that sought to stimulate dialogue about the future of social life

at Princeton. Prospects organized a design competition in the spring

of 2001 asking for proposals, primarily from students, for how spaces

along Prospect Avenue could be enhanced, changed, redefined or added

to in ways that would create a more diverse, inclusive and stimulating

social life on campus. The competition received 50 energetic and

provocative proposals and a jury comprised of university officials,

trustees, professors and students met publicly to award $5000 in

prizes. A year later, Prospects organized a second design competition

asking students to generate proposals for Whitman College, the first

of the new four-year residential colleges. The second competition

received more than 65 entries and awarded $10,000 in prizes to the

winners. For more information, download the 2002 competition catalogue

below or check out www.princeton.edu/~rethink. Taken

as a group, the Prospects competition proposals illustrate how the

university could combine ambitious plans for the new four-year college

system with thoughtful initiatives at Prospect Avenue to improve

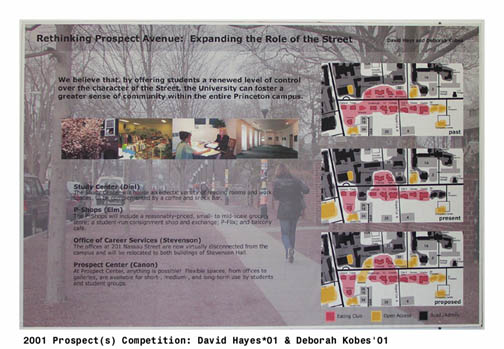

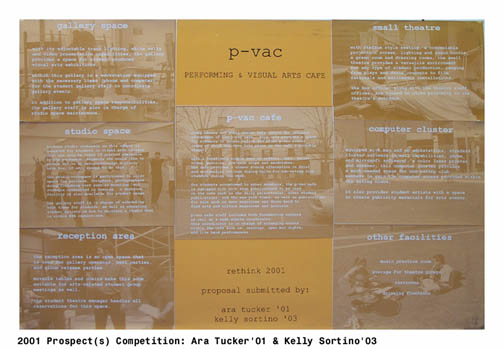

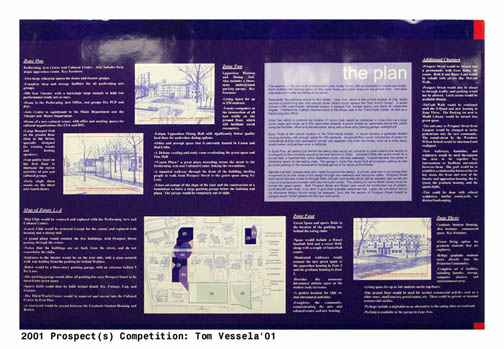

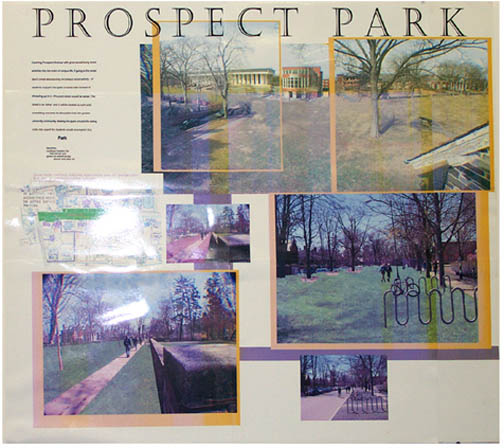

campus life comprehensively. The 2001 Prospects entries challenged

the university to reinvest in the street’s social geography

through urban design and policy initiatives. A number of the proposals

critiqued the university’s recent conversion of defunct clubs

into non-social spaces and its proliferation of new academic buildings

on Prospect Avenue, posing an alternative development model in which

the university creates spaces that would reinvigorate social life

at the street. Many entrants proposed building a performance hall,

galleries and art studios at available locations along the street,

citing the desperate need for these spaces on campus. Other entrants

advocated providing neutral social spaces at Prospect Avenue that

could be used by anyone for parties and other events. A number of

entrants proposed revitalizing the Third World Center (now the Carl

A. Fields Center for Equality & Cultural Understanding) or recommended

building a new cultural center at a central location on the street

to activate a spirit of multiculturalism. A few proposals even suggested

knocking down all physical barriers between the clubs and creating

a vast stretch of green space that students could freely traverse

and utilize for recreation. Pointing out that the university owns

much of the land surrounding the clubs, these proposals suggested

the possibility of far-reaching urban design initiatives. Accompanying

these urban designs were policy proposals aimed at making the clubs

more affordable, diverse and inclusive. One consistent proposal

was for the clubs and the university to coordinate purchasing, maintenance

and security operations to reduce membership costs and keep them

within reach of all students. Other proposals envisioned a highly

integrated dining plan allowing effortless meal exchange at any

club or university dining hall. As a body of ideas, the 2001 Prospects

proposals illustrated how an activist agenda on Prospect Avenue

could engender tremendous vitality at the street, while validating

the role of the clubs and improving their social contract with the

University. — Steve Caputo ’01 Steve Caputo majored in architecture and urban planning and received a certificate in East Asian Studies. He is currently working as a designer at Polshek Partnership in New York City. sacaputo@alumni.princeton.edu Write to PAW about this article.

|

||||||||||||||||||