Green technology holds the promise of significantly reducing carbon emissions and helping humanity to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. But without buy-in from individuals and groups — whether it’s building new habits and routines to conserve energy or galvanizing support to enact policies that will enable the transition to cleaner tech — progress is likely to occur far more slowly than what is needed.

As Princeton University undertakes its journey to reach net-zero campus carbon emissions by its 300th anniversary in 2046, it has made this kind of change a key component of its overall plan. In addition to installing a new system of energy-saving and combustion-free technologies powered by renewable energy sources such as solar and wind, Princeton is assessing its campus culture around energy use to further reduce energy demand and promote a conservation mindset.

“Addressing the climate problem is not a technical fix alone,” said Ijeoma Nwagwu, assistant director for academic engagement and campus as lab initiatives in Princeton’s Office of Sustainability. “We are on the road to doing everything we can technologically to get us to net-zero. But there is an underlying human element to addressing climate change. To see lasting progress, everyone has to be aligned with where we are going.”

The University has engaged Evidn, an international behavioral science company, to support the design, delivery and evaluation of pilot initiatives across campus to reduce energy consumption and contribute towards the attainment of Princeton’s sustainability goals.

“Figuring out the interplay between energy systems and behavior, between infrastructure and personal action, is part of the vanguard in sustainability thinking,” said Shana Weber, director of Princeton’s Office of Sustainability. “And working at the demonstration scale is essential. Any successful methods that emerge may very well be repeatable and scalable.”

Weber added: “If we expect to shift behaviors at any scale, a pervasive, persistent and sustained narrative from all levels of leadership is almost a prerequisite for success. We all need reminders when trying to adopt new habits — they rarely happen on their own, even if the desire is there.”

As a member of Princeton E-filliates Partnership, a corporate membership program administered by the Andlinger Center for Energy and the Environment, Evidn already is collaborating with Princeton scholars to research factors that may inhibit successful energy transitions globally and to devise interventions that could facilitate the adoption of new energy technologies. Evidn is also engaging postdocs, graduate students and undergraduates in thinking through behavior around energy use and developing solutions.

Evidn’s consultancy with Princeton is comprised of three stages. The first stage, which began in the summer 2021, is an analysis exploring the myriad underlying and interconnected factors that impact energy consumption on campus. The second and third stages, which will extend through 2022, focus on the initial design and testing of strategies grounded in behavior science.

To date, Evidn, in partnership with Princeton’s Office of Sustainability, has engaged individuals within more than 25 campus departments and groups.

John Pickering, chief behavioral scientist for Evidn and a non-resident fellow at the Andlinger Center, said Princeton can achieve approximately 80% of its campus carbon emissions goal through its combustion-free energy system (currently under construction) — which combines heat pumps, thermal storage and geo-exchange — along with energy improvements in its buildings, and also through its transition to renewable electricity sources. The remaining percentage, however, rests with the campus community, he said.

“There’s a component of this transition to net-zero that is behavioral, and it involves people and decision-making,” Pickering said. “Our aim is to understand what those behaviors and decisions are, and how we meaningfully influence them.”

“Princeton is leading the work of net-zero transitions internationally and what’s involved in doing that successfully,” he added. “There’s an opportunity for Princeton to show how all the parts interconnect — the technology, the science, the infrastructure, the behavior, the governance — and how all of it works together to achieve net-zero.”

Remember to shut the lights — and the fume hoods

Fume hoods used in labs throughout the University, such as those shown here in Frick Chemistry Laboratory, are an important safety feature, but they also are among the largest energy consumers on Princeton’s campus — requiring as much energy as one or more single-family homes. As the University is taking steps to reach net-zero campus carbon emissions, it is seeking ways to reduce their energy consumption by encouraging researchers to shut fume hood sashes when they are not in use.

Evidn’s initial analysis of the University community zeroes in on three areas. One is the use of fume hoods in Princeton’s labs. Across campus there are 738 fume hoods, which pull dangerous or odorous substances from the air.

Each fume hood can use as much energy as one or more homes, so it is important that their sashes (the barriers that protect researchers from experiments inside the fume hood) are shut when not in use. When the sashes are closed, the fans that pull air through the hood ramp down and use less energy.

In fall 2021, students in an undergraduate computer science course began developing a web-based dashboard that could help researchers in Princeton’s labs track their energy use.

For the project, the students examined energy consumption by fume hoods in the Icahn Laboratory. They used real-time data from the lab of Joshua Rabinowitz, professor of chemistry and the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics, to create a prototype for their dashboard.

When such a dashboard is fully realized, lab members could use it to monitor the impacts of their energy consumption and set energy use goals.

Morgan Teman, a junior who worked on the project team, said an eye-opening takeaway from her team’s research was when they took inventory of the energy-consuming fixtures in the Icahn Laboratory that were constantly in service, even when not in active use.

“Maybe it’s baked into campus culture or baked into the United States’ culture, but no one is recognizing or registering that things are always running, and you need a display to be able to recognize that and impact change,” Teman said.

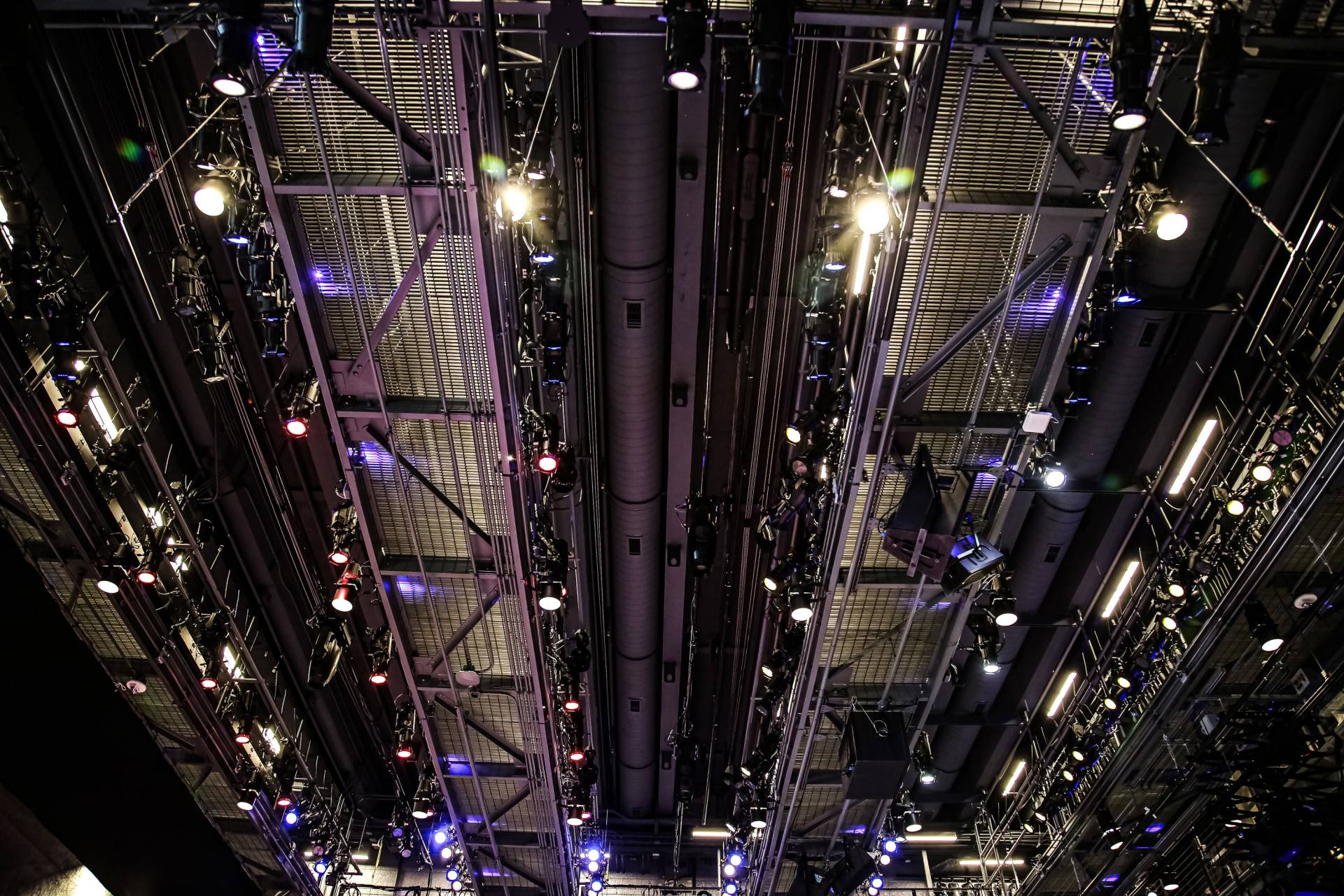

Another area where individual actions can make a significant impact at Princeton is in the use of events facilities including classrooms and lecture halls, arts performances spaces, and athletics facilities. Once a space is reserved for an event, its heating or cooling systems must be turned on (depending on the season), along with lighting and any audio, visual and digital capabilities. These all consume large amounts of energy.

If the systems are enabled too early before an event or shut down long after they are needed — or if they are left running continuously — the energy wasted is significant.

Event spaces across campus consume large amounts of energy, especially when their systems are enabled too early before an event or shut down long after they are needed — or if they are left running continuously. Event schedulers can help to cut back on energy usage by scheduling only for the time a space will be in use, or by cancelling a reservation if an event no longer is being held.

Finally, there is an opportunity for the University to target student, faculty and staff habits more broadly. While this represents a smaller percentage of energy use — student residential hall energy consumption, for instance, accounts for about 10% of Princeton’s total — motivating the campus community to use energy more intentionally day to day offers an opportunity for engagement and community building around sustainability.

“On campus it’s the lowest impact of the three areas, but it ties into the overarching point, which is we need a cultural and behavioral glue that brings this all together,” Pickering said.

When it comes to behavioral science, getting people to change their behaviors is not the hardest part — it’s getting that behavior change to last, Pickering said. And that can’t happen unless there is systemic change from the bottom to the top of any organization. In other words, individual choices and actions are important, but so is their context and meaning within a larger group or organization.

“If it’s not part of a call to action, people don’t realize why they are doing it, and the behavior atrophies quickly,” he said. “So you need a suite of strategies. It’s the overarching vision and the mission, and the reminder of the why.”

The power of the individual

Individual change starts with helping people to feel that they have agency, and that their actions will make a difference in the global climate problem, said Elke Weber, the Gerhard R. Andlinger Professor in Energy and the Environment, professor of psychology and the School of Public and International Affairs.

Weber, who studies human responses to climate change and energy transitions, explained that people make decisions by three different processes: through reason, through emotion, or based on rules. When all three of these come into play appropriately in a decision, lasting behavioral change can take root.

“Behavior change requires intimate knowledge about the group whose behavior you are trying to change — what their goals and fears and hopes are, and how they prefer to process information and from what sources they get it,” Weber said.

Thought also needs to be given to how to package information. “If you build it, they might not come,” Weber said. “So engineering solutions in their own right are not sufficient.” Encouraging change in a way that resonates with the community is essential, and something that needs to happen on a large scale as governments and institutions consider ways to reduce energy consumption and enact new policies and technology.

Policy solutions need well-considered research, targeting and messaging, Weber said, especially since motivating people to make certain choices can take on many different forms. “I think our policymakers are not fully aware of the wealth of information related to human behavior that is available and that they need to consider to formulate good policies and to implement them optimally,” Weber explained. “Let’s say you want to subsidize electric cars. You can do that in different ways. You can do that at the point of purchase or as a refund on people's annual income tax return. The first way is far superior for a long list of psychological reasons.”

Learning from the community and as a community

As with most of Princeton’s sustainability initiatives — many of which are at the forefront of similar energy transitions occurring nationally and internationally — faculty, postdocs and students are able to join through coursework and research.

Holly Caggiano, a Distinguished Postdoctoral Fellow at the Andlinger Center, is one researcher who will be involved with faculty, staff and student initiatives that emanate from Evidn’s research about Princeton’s campus culture and specific energy conservation needs.

Caggiano said she is interested in examining what actions around sustainability are learned on campus and formed into practices that become part of our everyday lives. Through her research, she also plans to investigate whether students feel they have agency to make change, how they respond to top-down directives, and what is the impact of peer influence.

“Princeton has the opportunity to not only reduce its environmental impact, but also engage in conversations with students, faculty and staff in a more holistic way that informs the way they think about energy and resource consumption,” Caggiano said.

Such findings can help inform effective messaging around energy use, not just at Princeton, but elsewhere. “One of the most exciting parts of this work is the chance to situate Princeton as an incubator for change that starts on campus, but follows the diverse members of our community around the world,” she said.