Detailed records that reveal more information about a controversial period in the lives of aviator Charles Lindbergh and his wife, Anne, were opened Thursday at Princeton's Firestone Library.

Six boxes containing writings relevant to the Lindberghs' views on American neutrality before World War II, as well as more than 1,500 letters in response to their opinions, were opened. The action officially makes the materials available to researchers using Firestone's Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.

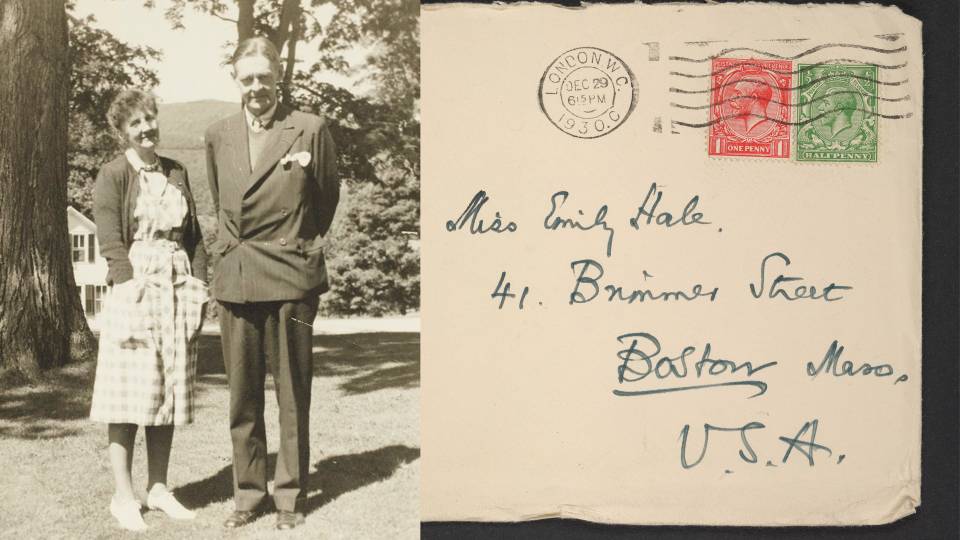

The Lindberghs gave the papers to Princeton in 1941 with the stipulation that they be unsealed only after the death of both Charles and Anne. Anne died early this year, Charles in 1974. In the early 1930s, the couple had lived near Hopewell, site of the tragic kidnapping of their first child. Charles, who also invented a pump that later paved the way for organ transplants, had conducted medical research in a campus laboratory during that time.

In 1927, Lindbergh garnered worldwide attention as the first person to fly solo and nonstop from New York to Paris. Just five years later, he and his wife suffered the kidnapping and death of Charles Jr. To escape the media frenzy surrounding the subsequent "Trial of the Century," the Lindberghs moved to Europe, bringing the couple closer to a world that was drifting toward war.

What Lindbergh saw in Europe -- particularly the growing strength of Germany's Luftwaffe -- made him an avid anti-interventionist, a position he championed upon returning to the United States in 1939 when he became the key spokesperson for the America First Committee. While Lindbergh's position changed with the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the controversy surrounding his thinking during those tense times remains to this day and is a prominent part of the Princeton papers.

The Princeton collection is a small portion of Lindbergh materials housed in archives around the country, but is the first to be opened. Most of the family papers are at Yale University, where they are still sealed. Princeton alumnus and trustee A. Scott Berg, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for his 1998 biography "Lindbergh," says that the couple was "highly unusual in that they recorded so much." Berg, who has written biographies of book editor Maxwell Perkins and film mogul Samuel Goldwyn and who is now chronicling the life of Woodrow Wilson, says that "one would be hard-pressed to find anyone who was not a president who had this much material recorded and saved."

Berg explains that even as a boy Charles had the tendency to save and catalog things, and that Anne "felt that no event was ever complete unless she had written about it." Berg also credits the Lindberghs for feeling that they had a responsibility to engage with and characterize their changing world.

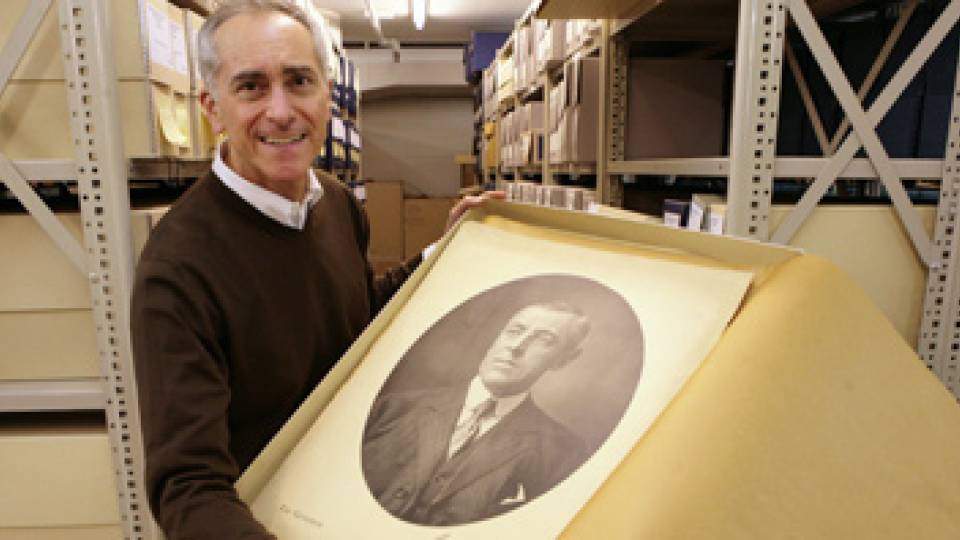

Describing the Lindberghs as "pack rats at the highest level," Don Skemer, curator of manuscripts at Firestone Library, marvels how the couple saved everything, from fan mail to the most unflattering criticism. Their conscientiousness should prove hugely beneficial to historians and biographers who now can learn from the Lindbergh archive. In 1993, Skemer and Berg, along with Reeve Lindbergh, the youngest of the couple's children, temporarily opened the original wooden crate of documents, having received permission from Anne for the purpose of Berg's research.

"What was in the crate was exactly what Julian Boyd, the University librarian at the time, had described on the outside," says Skemer. The contents were later parceled out into the six boxes. One contains the manuscript, edits, galleys and final publication of Charles' article "A Letter to Americans," which was printed in the journal Collier's on March 29, 1941. A second holds the manuscript and entire publication cycle of Anne's book "The Wave of the Future: A Confession of Faith," published in 1940. The other four contain between 1,500 and 2,000 letters from the general public responding to these two publications.

As most of the letters in the boxes reflect, the majority of Americans in 1940 were opposed to intervening in Europe. Berg compares Lindbergh to a "Paul Revere warning the nation that Europe would enter a war and that the United States would not be ready." Berg counts that between October 1939 and October 1941, Lindbergh delivered about two dozen speeches and radio addresses and wrote about six articles urging America to stay out of the war.

In "A Letter to Americans," Lindbergh points a finger largely at Britain as being the "agitator" ready to drag the United States into war. "The drafts were dated, which is somewhat unusual," Skemer says. "One can precisely trace the process and watch Lindbergh wrestling day by day in December 1940 and January 1941 with some critical thoughts, such as who exactly were the forces leading America toward war in Europe."

Soon after the article was published, in an infamous speech in Des Moines, Iowa, Lindbergh included the Roosevelt administration and Jews as "agitators for war." By this time, Lindbergh already had been attacked for a perceived pro-Nazi sentiment, not least because he would not relinquish the Service Cross of the German Eagle awarded to him in 1938 by Hermann Goering during one of Lindbergh's trips -- at the request of the U.S. military -- to survey German air power. Unsurprisingly, the Des Moines speech further angered and alienated thousands of Americans, planting deeper a controversy that never died.

With "The Wave of the Future," Anne, much beloved by the public, also faced a backlash. In "Lindbergh," Berg states that Anne's book was, in its day, almost as reviled as Hitler's "Mein Kampf." Berg explains that Anne naively suggested that the war in Europe was not a "fight between good and evil" but a struggle between "forces of the past" and "forces of the future."

To many Americans sympathetic to the plight of Europeans suffering from Nazism, and indeed to many Americans already angry with Charles, Anne's book seemed to suggest that there was nothing to do but let Nazi Germany or Communist Russia get on with it. But Anne did have supporters: The Princeton papers include a letter from poet W.H. Auden, who gently warns that her book might be misunderstood.

Behind these controversial publications lies another story -- that of a husband and wife helping each other as writers. The editing notes made by Anne and Charles about each other's writing offer insights into what Berg describes as the "symbiotic marriage" the Lindberghs had in their literary lives.

The drafts of the two manuscripts give a good sense of both Anne's and Charles' writing processes, efforts that culminated in real literary successes: "The Spirit of St. Louis," Charles' account of his 1927 trans-Atlantic flight, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1954; and Anne's "Gift from the Sea," published in 1955, reached bestseller status and an audience of women around the world.

(For an inventory of the collection, click here and then click on "Lindbergh, Charles.")

Contact: Justin Harmon (609) 258-3601