Princeton senior Zachary Squire was first drawn to the field of classics by a fascination, shared by many youngsters, with Greek and Roman mythology. That early interest eventually grew into a broader appreciation of the study of ancient civilizations.

"When I was younger, I had a very strong tendency to idealize the past. Greece and Rome were great stories, and I took myths as great examples. These were cultures and civilizations that I really admired and respected," Squire said. "That feeling evolved into more of a respect for the study of classics itself, as an interdisciplinary academic field in which you look at politics, history, literature and philosophy all together."

While Squire found outlets for his varied interests within Princeton's classics department, he also excelled in courses across the University -- charting a well-rounded path to becoming valedictorian of the class of 2008. Squire will deliver the valedictory address at Princeton's Commencement ceremony on June 3.

Squire's 10 A+ grades include courses in economics, electrical engineering, geosciences and physics. In addition to his independent work in classics, he has participated in research projects on quantum cascade lasers in the engineering school and on trade policy in the politics department.

This immersion into an array of academic endeavors is just part of what has made Squire's Princeton experience so memorable.

"For undergraduates, this isn't just a place where you come and get an education -- you live here for four years, you're involved in campus life, you make friends and meet people," he said. "The friends I've made here are ones I'll value for a very long time, and I'm sure I'll be friends with them for years and decades to come. That's been a huge asset to my time at Princeton -- the quality of the people here, and how fun and interesting they are."

Faculty members who have worked closely with Squire cited both his sophisticated intelligence and his sense of humor as qualities that helped him thrive.

"What made Zachary stand out for me early on was a remarkable independence and even-handedness in the face of sharing a situation everybody was in (that of being new to Princeton), which never amounted to 'playing it cool,'" said Constanze Güthenke, an assistant professor of classics who was Squire's freshman adviser and his instructor in three classes. "Rather, it seemed to betray a genuine, level-headed fascination with and observation of the world around him, asking himself some serious questions, but always willing also to see the slightly more absurd side of the situation (it is after all a strange time and place to be arriving in one's first year). What certainly impressed me was that he was also the first freshman I had ever come across who put on his form of 'interests and intentions' that having a good kitchen so as to cook excellent food was an aim to have not just in college but in life, aside from wanting to pursue his interest in ancient languages and thought.

"What became clear over the next years is that Zach is someone who wears his learning lightly and gracefully," Güthenke said. "He simply and genuinely finds it easy, normal and pleasurable to think, and he has an admirable talent to articulate that thinking with ease and with precision -- and to make it look easy. Yet the ease in that case is never one of complacency."

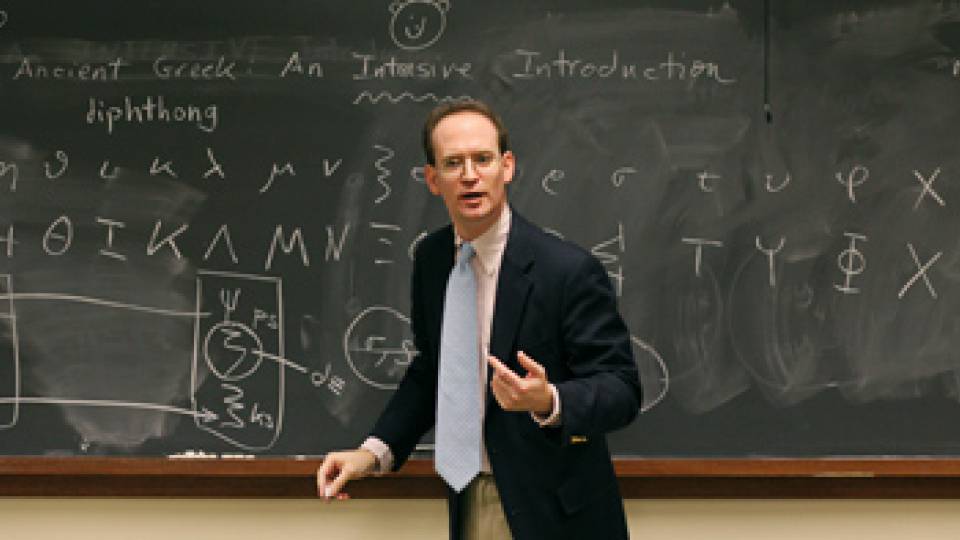

Robert Kaster, the Kennedy Foundation Professor of Latin Language and Literature, taught Squire in courses on the philosopher Seneca and on Latin language and stylistics.

"I've never seen a freshman come to college with the grasp of Latin that he had," Kaster said. "It wasn't just that he knew his grammar, syntax and vocabulary. He really had an amazingly wide range of reference and, plainly, had just read a lot, which would do credit to a student graduating from college much less beginning as a freshman.

"In the Seneca course, he showed that he was thinking deeply about the texts we were reading," Kaster added. "He could anticipate the direction in which the discussion would be going in any given topic and get there a couple of steps more quickly."

Kaster said he has enjoyed Squire's "more than slightly sardonic sense of humor" and their conversations on topics outside of classics, such as politics. Güthenke also complimented Squire's breadth of interests: "How many students do you meet who can explain to you in brief but in depth Cicero's political philosophy, British economic policy, the relative value of Italian opera and the workings of quantum cascade lasers?"

A classical foundation

Squire grew up in New York City, where he performed in more than 200 productions as a member of the Metropolitan Opera Children's Chorus. He began studying Latin in sixth grade and continued the subject through his time at the Collegiate School, where he was valedictorian of the class of 2004. He was attracted to Princeton by the strength of the classics department as well as "the social atmosphere and, generally, the quality of the people who were here."

In his classics studies, Squire has focused particularly on politics, political theory and law. His senior thesis explored the importance of property rights in the works of the Roman philosopher Cicero and how his perspectives differed from previous Greek models.

Squire's thesis adviser, Brent Shaw, the Andrew Fleming West Professor in Classics, described the work as "the finest piece of research of this type that I have had occasion to read during my time at Princeton."

Noting that Squire set a new benchmark for debate on Cicero and property rights, Shaw added that he "had the perspicacity to see a very good subject and a talent that was equal to the task. Since an enormous amount of scholarship already exists on Cicero -- even on these particular aspects of his thinking -- a fairly high bar was set to do any innovative research with the problem of private property and the nature of the state. He both sighted the subject and was able to do so well with it, I like to think, not just because of his native abilities (which are considerable), but also because of the superlative training that he received in the classics here at Princeton."

Another highlight of Squire's time in the classics department was a trip to Greece he took after his sophomore year to study civic architecture, supported by the department and the Program in Hellenic Studies. "I was able to get a very good sense of the physical context in which all the history and literature that I've read took place, which I think was very important for filling out the picture of how the ancient world really worked," he said.

Outside of classics, Squire cited a course on the anthropology of law, taught by Lawrence Rosen, the William Nelson Cromwell Professor of Anthropology, as one of his most formative academic experiences. The course examined the relation between formal legal institutions and the social and cultural factors influencing their development.

"It trained you to step outside whatever assumptions or value systems that you're in and to realize there are different ways to organize a variety of human experiences in some sort of culture," Squire said.

A similar sensibility guided his academic and extracurricular pursuits at Princeton. He spent last summer as a researcher in the Center for Mid-Infrared Technologies for Health and the Environment headed by Claire Gmachl, a professor of electrical engineering. There he focused on possible applications for quantum cascade lasers in the field of trace gas detection, and explored the interaction of scientists and policymakers and the role of scientific expertise in elected government. During his junior year, he worked as research assistant to Helen Milner, chair of the politics department, on a statistical analysis of Congressional voting patterns on trade policy.

Outside the classroom, Squire has served as public safety and governance liaison for the Undergraduate Student Government's Undergraduate Life Committee, working on disciplinary issues. He has been policy director for the Princeton Model Congress, which hosts an annual conference in Washington, D.C., to engage high school students with current issues in public affairs. Squire also is a member of the Princeton Tower Club.

Squire's selection as valedictorian caps an impressive collection of academic honors. He was twice awarded the Shapiro Prize for Academic Excellence and also received the George B. Wood Legacy Sophomore Prize, the Quin Morton '36 Writing Seminar Essay Prize and the classics department's highest honor for sophomores or juniors, the Stinnecke Prize. Squire was elected to Phi Beta Kappa this fall.

After graduation, Squire will work for D.E. Shaw & Co., a New York-based investment firm. Although he had considered going to law school or pursuing a career in politics, he is excited about the opportunity to embrace yet another different field.

"I had never considered a career in finance, but the opportunity presented itself," he said. "Right now, I'm focused on giving it a really good try."