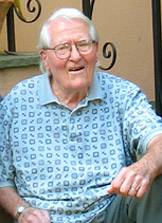

Franklyn Van Houten, a Princeton University geologist whose interest in simple sediments propelled him for dozens of summers on a scientific odyssey through the American West, Canada, Venezuela, Colombia, Morocco, Tunisia and Egypt, has died at age 96.

Van Houten, a professor emeritus of geological and geophysical sciences who joined the Princeton faculty in 1946, died at home in Bethlehem, N.H., on Aug. 27. His pioneering research on a rock formation known as the Newark basin also made him an authority on the geology of New Jersey.

Known to friends, colleagues and students simply as "Van," Van Houten spent much of his career extracting geological history from rock strata, the thin veneer of sediments coating the Earth's crust. His specialty was sedimentology, the study of history buried in sedimentary rock. The field long has been vital to exploration for oil and, more recently, for metals and nonmetallic resources, and has served as a main source for scientific knowledge about Earth history.

The importance of his work in understanding uranium deposits is cited in the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, "Annals of the Former World," by John McPhee, Princeton's Ferris Professor of Journalism. Van Houten's discovery of a consistent geological pattern in which lake levels rose and fell is now known as the "Van Houten cycle." And his studies of phosphorous deposits and banded iron formations in sediments made him an early adherent of the "Snowball Earth" hypothesis postulating that the planet's surface froze more than 650 million years ago.

"He always had his eye on important geologic problems," said Lincoln Hollister, a Princeton professor of geosciences and a longtime colleague. "His work on the Triassic Newark basin set the stage for interpreting past climates from the sediment record."

Van Houten's extensive travels and keen eye for detail are still benefiting Princeton students. "We still use his guidebooks to guide field trips for our classes," Hollister added.

Van Houten was born in New York in 1914, a son of Charles and Hessie Bosworth Van Houten. He received a bachelor's degree from Rutgers University and his Ph.D. from Princeton in 1941. While completing his doctoral thesis, he taught at Williams College from 1939 to 1942.

He served in the U.S. Navy during World War II as a member of the team led by the late Princeton Professor Harry Hess that ran the campaign against the German U-boats in the North Atlantic. Van Houten joined Princeton's then-Department of Geology as an assistant professor in 1946 after he was released from active duty with the rank of lieutenant. He was named a full professor in 1955, a position he held until 1985 when he retired.

He wrote many articles on sedimentary and regional geology in technical journals. He edited a book, "Ancient Continental Deposits," and contributed chapters to several books on ancient climates and soils. He was a fellow of the Geological Society of America and a member of several professional organizations, including the American Association of Petroleum Geologists and the International Association of Sedimentologists.

In 1985, the Society of Economic Paleontologists and Mineralogists bestowed the William H. Twenhofel Medal, the highest award granted for excellence in sedimentary geology, upon Van Houten. The citation, presented by M. Dane Picard, one of his Princeton students, read: "For four decades of distinguished research and achievement in the study of the relations between deposition and tectonics, superior teaching and training of students, and demonstrating what a difference one excellent, industrious geologist of great integrity can make."

At Princeton, Van Houten taught everything from introductory, freshman-level courses to graduate seminars. He served for many years as an undergraduate adviser and director of graduate studies in his department.

He was a dedicated teacher. "When I started graduate school at Princeton, the very first lecture that I heard was Professor Van Houten on the last 60 million-year history of Wyoming," said Kenneth Deffeyes, a Princeton professor emeritus of geosciences. "I had gone to high school in Wyoming, and was an undergraduate in Colorado. I had been on many geological field trips, but Van Houten's lecture was better than anything that I had ever heard in Wyoming."

Van Houten also was known as a perfectionist. "In the classroom, he was a stickler for definitions, articulation," said Tullis Onstott, a Princeton professor of geosciences who first met Van Houten when Onstott was still a graduate student. "In his field of sedimentology, they communicated with a special language of their own, so he was as much a language teacher as a scientist." Van Houten almost always walked to and from his Princeton home and on trips around the campus. He frequently donned a black beret and strode toward his destination at a good hiking pace, often whistling.

In 1998, a student named a fossil after him. Former Van Houten student Phil Gingerich was part of a University of Michigan team that discovered the fossilized jaws and 13 teeth of a shrew-like insect eater. He was able to convince his colleagues to name it "Batodonoides vanhouteni." In an interview in the Princeton geology department's newsletter, The Smilodon, Gingrich said he did so because Van Houten "had such a great influence on me when I was a student."

Van Houten's son, David, recalled his father's summer scientific forays, which he remembers well because the professor often brought along his wife, Jean, and their three children. "It was great for us all to grow up with," said David Van Houten, who once brought home a pet lizard from a research trip to Nevada. "We would stay at a ranch. He would take us into the field every day, and we would roam through the desert and across the mountains."

The family transport system was a Willys Jeep station wagon. "We would camp under the stars, prepare meals on a two-burner Coleman White gas stove, and develop a taste for cold water from a bug-encrusted canvas Desert water bag hanging on the front grille of our Jeep," said Van Houten's other son, Boz, of Eugene, Ore. "These trips are fondly remembered."

Van Houten lived in Princeton until 2007 when he moved to Bethlehem, N.H., to live with his son, David.

He was predeceased by his wife in 1997 and his grandson, Ian Van Houten, who died in 1999. In addition to David and Boz, Van Houten is survived by his daughter, Jean Evans, of Bluefield, W.Va., and four grandchildren

A memorial service is planned for 4 p.m. Friday, Nov. 12, in the University Chapel.