Name: Katja Guenther

Title: Assistant Professor of History and the Johanna and Alfred Hurley *61 P76 P82 P86 University Preceptor

Guenther trained as an M.D. in Germany before she earned a Ph.D. in the history of science from Harvard University. She also holds an M.Sc. in neuroscience from the University of Oxford. Guenther joined Princeton as an assistant professor of history in 2009.

As a medical student, Guenther took classes in philosophy and medieval literature in addition to pathology and pharmacology. During clinical rotations in hospitals in Germany, and later in France and the United Kingdom, she became fascinated by the impact of cultural practices on medicine. In observing how medicine was practiced differently in different contexts, she began to ask how it had developed and why it was done that way. Guenther had discovered a new intellectual passion: studying medicine through the lens of history.

Today, teaching at Princeton, Guenther interweaves her training as a physician, neuroscientist and historian to study the history of modern medicine and the mind sciences. She connects the sciences and the humanities, certain that a historical approach leads to deeper understanding of complex areas of study such as brain research.

Among the undergraduate courses Guenther has taught are "History of Medicine and the Body" and the seminars "Broken Brains, Shattered Minds: Disease and Experience in the History of Neuroscience" and "Medicine and Deviance: Defining Disease in the Modern World." This semester, she is teaching a new graduate seminar, "Freud to fMRI — Readings in the Histories of Mind and Brain."

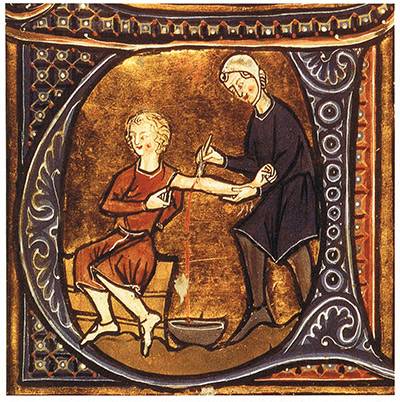

In her teaching, Guenther discusses how practices of medicine have changed across cultures and throughout time; the scene above is of medieval bloodletting. (Image courtesy of Katja Guenther)

Guenther has published a number of articles and edited and translated into English one of Sigmund Freud's early texts, "Critical Introduction to Neuropathology." She recently completed a book manuscript focusing on the history of psychoanalysis and the neuro disciplines (neurology, neurosurgery and the neurosciences). She is working on a new project on mirrors in the mind and brain sciences to explain why the mirror is an object of fascination for a wide range of researchers, and to examine how it has allowed the development of new theories of the mind and approaches to treatment.

"Katja's work bridges the divide in the mind sciences between laboratory approaches and psychoanalysis, showing how both grew out of 19th-century physiology," said William Jordan, the Dayton-Stockton Professor of History and chair of the department. Describing Guenther as a "genuinely exciting scholar," Jordan also commended her teaching, noting in particular that "many of the pre-meds at Princeton yearn to learn more about the technical history of medicine, and Katja's 'History of Medicine' course offers them a rigorous entry into this subject."

Below, Guenther describes making the connections between history and science and what inspires her teaching and research.

Why did you study medicine?

I decided to study medicine because I was interested in science and I was also interested in people and enjoyed interacting with them. Medicine combines complex specialized knowledge and the human in unique ways. It is about understanding how the body functions, but just as crucial for medical practice is the relationship between doctor and patient. The doctor has to explain to the patient how a treatment works, she has to humanize what can be very abstract and technical knowledge.

Why did you follow an M.D. with a Ph.D. in history of science?

During my clinical rotations in different European countries, I came to the realization that the human side to medicine was even more important than I had previously imagined. To give you an example, in the German context, doctors are more likely to treat hypertension (high blood pressure) by giving drugs. In France, however, I found that doctors were much less likely to give medication, and would talk instead about diet and exercise. It wasn't simply that the human element to medicine existed alongside but remained distinct from the scientific technical element; this experience suggested that they were closely intertwined. That was what sparked my interest in the history of science. I was fascinated by the ways in which cultural factors could play a profoundly important role in the way in which medical ideas developed and how treatments were performed.

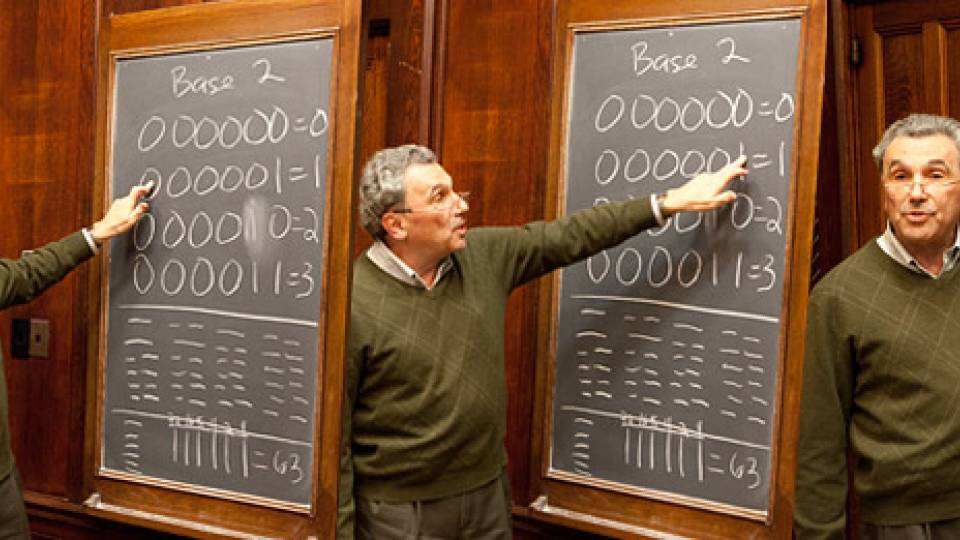

This spring, Guenther is teaching "Freud to fMRI," a graduate seminar that explores human subjectivity and how "scientific and cultural perspectives are entangled" in the mind sciences. (Photo by Denise Applewhite, Office of Communications)

What do you hope students learn about the history of medicine?

I want to encourage my students to think in these terms as well. One of the major historical problems in my history of medicine survey course is the persistence of the humoral system for over 2,000 years. Well into the 19th century doctors and patients understood disease in terms of the balance of bodily liquids: blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm. To us today this seems wrong-headed, but such a judgment does little to help us understand how the humoral system remained dominant for such a long time. What we need to do is to go beyond the physiological understanding, and work out how it impacted upon the relationship between the physician and the patient. In contrast to much modern biomedicine, the humoral system was comprehensible to both parties. The theory of the humors helped the patient make sense of their experience, and provided the doctor with relatively clear therapeutic possibilities. This was a mutually affirming relationship.

What ideas have you found most engage students?

Medicine has enormous cultural authority today. Not only do we begin and most often end our lives in medical settings, medicine pervades the life that comes in between. Such authority helps produce discontents, and we don't need to look far to see a number of activities and cultural practices that present themselves as reactions or antidotes to modern biomedicine. This means that a history of medicine in the modern world often has to step outside of the boundaries of the hospital and doctor's office, and students find it very revealing to take the history of medicine approach to seemingly non-medical phenomena of everyday life. For example, in the fall, Princeton senior Elektra Alivisatos, a student in "History of Medicine," researched prenatal yoga and the history of yoga in the West. She went to one of the yoga studios in Princeton to interview the participants, and produced an oral history. She then turned her research into a five-minute podcast that included snippets from her interviews.

What are goals for the graduate course "Freud to fMRI?"

The mind sciences seem to me an exemplary case of the ways in which scientific and cultural perspectives are entangled. Few fields make such strong claims about human subjectivity, and the imprint of broader cultural assumptions is particularly clear in the mind and brain sciences. In the course we are discussing questions like: What forms of subjectivity do the mind and brain sciences promote, and what ideas about the self do they reflect?

In the present, as the neurosciences dominate the study of the mind and brain, a further question is raised: What impact has neuroscience had on broader society? And what impact should it have? We are witness today to the rise of several neuro-hyphenated disciplines like neuro-ethics and neuro-economics. Their existence is testament to a profound optimism that neuroscientists will be able to redefine existing bodies of thought. But in my opinion modern neuroscience has often been insufficiently attentive to the way in which it draws on psychological categories, and to the types of subjectivity that it produces. We need to think carefully through these relationships to recognize the potential of the neurosciences, but also to understand their limitations.

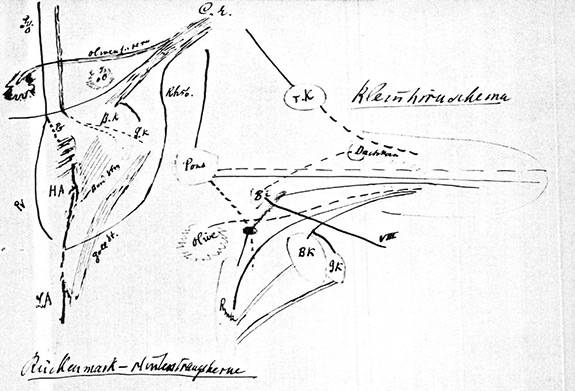

Guenther explains that the "tense interplay" between the "psy" and "neuro" disciplines can particularly be investigated in the work of Freud, whose study of neurology laid the groundwork for the development of psychoanalysis. Guenther translated Freud's 1887 book, "Critical Introduction to Neuropathology," which includes this drawing by Freud of the spinal cord, nuclei of the posterior tract and cerebellum. (Freud illustration courtesy of Psychoanalysis and History, Vol. 14 No. 2, 2012)

How do these ideas play out in your own research?

If we look at the history of the mind and brain sciences, and this is central to my research, we can see a tense interplay between the "psy" and the "neuro" disciplines (psychology, psychiatry and psychoanalysis, in contrast to neurology, neurosurgery and the neurosciences). Nowhere is this clearer than in the work of Sigmund Freud. When I was conducting research for my book at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C., I came across a short book manuscript written by Freud in 1887. It was a very exciting find. There are very few major Freud texts that haven't been published, and this one seemed especially important. In his letters to his fiancée from the time he described the project as a particularly "bold" one. He worried that the ideas he expressed there were too radical to gain traction, which in part explains why he never published it. Together with colleagues in Tübingen, Germany, the Freud scholars Albrecht Hirschmüller and the late Gerhard Fichtner, I edited the manuscript, and translated it into English.

What is most fascinating about the text is that it was deeply embedded within the German neurological tradition. Freud gave it the title "Critical Introduction to Neuropathology." In an article that appeared last year in Modern Intellectual History, I show how his radical re-reading of neurology laid the groundwork for the development of psychoanalysis. Freud's new theory of the mind was dependent upon his close engagement and working through of the neurological tradition.

In a similar way, in my recently completed book manuscript, I look at how different notions of the nervous system promoted different ideas of the self. I tell a history about these competing visions that gives context to what some historians have called the modern "cerebral subject," according to which we identify ourselves fully with our brains. When we understand this history, recognize its complexity, I think it allows us to look afresh at modern neuroscience, to welcome its contributions, but also to be wary of its limitations in understanding the world in its historical complexity.