From the Dec. 5, 2005, Princeton Weekly Bulletin

One afternoon, on a whim, an ambitious junior named Cara Sheffler sent an e-mail message to a professor she had never met, Daniel Heller-Roazen of the Department of Comparative Literature. The note explained that she was eager to learn Old Provençal, a language spoken in Europe in the 12th century by a band of traveling poets known as the troubadours. Would he teach it to her?

The answer came back swiftly: “Sure, I’d be happy to.”

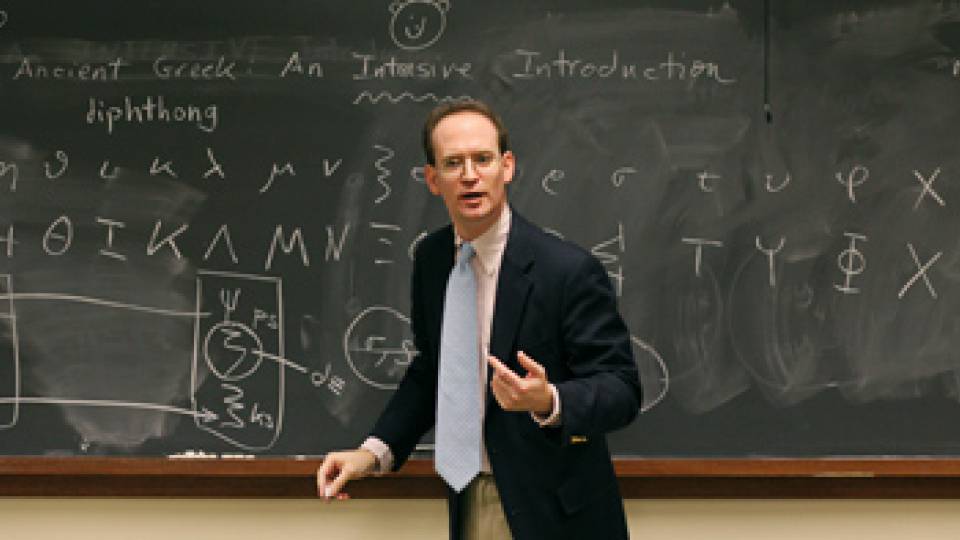

Heller-Roazen, who is fluent in nine languages in addition to Old Provençal, possesses a breadth of knowledge seldom seen even in an interdisciplinary field such as comparative literature. A scholar who probes the intersections between philosophy and literature, he is a teacher known for his talents in communicating complex ideas clearly and eloquently and for his intellectual generosity.

Sheffler, who graduated in 2004 with a degree in comparative literature, is now hoping to continue her study of Old Provençal when she enrolls in graduate school. Her independent study with Heller-Roazen “was, by far, the most intense and rewarding academic experience I have ever had,” Sheffler said. “I was pretty much shell-shocked the first time I found myself on the other side of his desk with a stack of books in about five different dead languages (both Romance and Germanic) that I did not know from Urdu. By the end of the semester, I was able to read in all of them, on top of having learned Old Provençal.”

Learning new languages has come naturally to Heller-Roazen since childhood. His mother, a professor, moved the family to Italy for a year when Heller-Roazen was 8. Deborah Heller was on a sabbatical from her position as a professor of humanities at York University in Toronto.

“My parents put me and my brother in an Italian school,” he recalled. “I remember for the first while we couldn’t say anything. By Christmas we were talking.”

As a youngster he attended a French school in Toronto, took German and ancient Greek in high school and studied Latin at the University of Toronto, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in philosophy.

He enrolled in graduate school at Johns Hopkins University with the intention of making German his main field, but after earning a master’s degree in German he decided to pursue medieval studies and, in particular, the relationship between poetry and philosophy in the Middle Ages. While a graduate student, Heller-Roazen published three major translations of the contemporary Italian philosopher and literary theorist Giorgio Agamben, as well as a fourth edited and translated book of Agamben’s essays. He also added classical Arabic, Biblical Hebrew, Old French and Old Provençal to his repertoire. Yiddish made the list after he enrolled in an intensive summer program a few years ago.

Translation issues

In 2000 Heller-Roazen was awarded a Ph.D. in comparative literature from Hopkins and was hired by Princeton. Last summer he was promoted to full professor.

“In very short order, Daniel has become an internationally recognized young scholar in medieval studies and contemporary critical theory,” said Sandra Bermann, chair of the comparative literature department. “His work has added enormously to what we can offer students in these fields, and it has energized a number of interdisciplinary groups on campus.”

Heller-Roazen’s knowledge of so many languages has helped him explore issues arising from the transmission and translation of philosophic texts. He is particularly interested in the fact that many classical Greek works, such as the writings of Aristotle, reached the West in the 12th century through Arabic translations.

“The bulk of classical letters were translated to the West not directly from Greek, but through Arab intermediaries,” he said. “They went from Arabic into Latin. Arabic is the second classical language in a way — before Latin and right after Greek. More texts existed in Arabic translation than in Latin translation. This chapter has been somewhat overshadowed in our histories of knowledge and culture, and one of the things I’m interested in exploring is the ways in which this affects the history of knowledge and power.”

Heller-Roazen currently is preparing the Norton Critical Edition of “The Arabian Nights,” a collection of popular tales whose origins also involve issues of translation.

“There is no known original version of ‘The Arabian Nights’ — the oldest text we have is clearly a translation,” Heller-Roazen said. “It has no author — no one signed it. It is clear its origin is not Arabian; it’s either Persian or more likely Indian. Europeans for a long time considered it the most famous of Arabic works, but many Arabs don’t think of it as a great text and don’t think of it as an Arabic text.”

Heller-Roazen relishes exploring such quandaries in the courses he teaches, including “The Literature of Medieval Europe” and “The Classical Roots of Western Literature.” He finds Princeton students are eager to learn about complex subjects such as the ones he tackles.

“I’m regularly bowled over by the excitement and dedication of students here,” he said. “I remember telling a student once that maybe she would be interested in reading part of ‘The Romance of the Rose’ for her junior paper. The book is 20,000 verses, about 450 pages, and it’s hard to get through for most graduate students. She came back the next week having read the whole thing. The most important thing for students, I think, is to be excited about the subject matter and to throw themselves into it.”

Heller-Roazen is known for reciprocating his students’ enthusiasm. Senior Zachary Woolfe met Heller-Roazen for the first time when both were in Venice for the summer. Woolfe had received a Dale Summer Award to study theater architecture, and Heller-Roazen was a visiting fellow there.

“He was incredibly generous with his time and expertise,” Woolfe recalled, “showing me around the notoriously hard-to-navigate city and giving me invaluable advice about my project.”

This year, Heller-Roazen has become an informal third adviser for Woolfe’s thesis. The two meet frequently to discuss Woolfe’s work.

“He has pushed me to think more clearly and deeply,” Woolfe said. “Beyond the tremendous amount of information he conveys at every meeting, his enthusiasm for pure, voracious learning is an inspiration in itself.”