Students in a recent session of Dan Nosenchuck's mechanical design class at Princeton University put aside the complex tools they're using to build a sophisticated robot and picked up a pad of sticky notes to plaster along the wall.

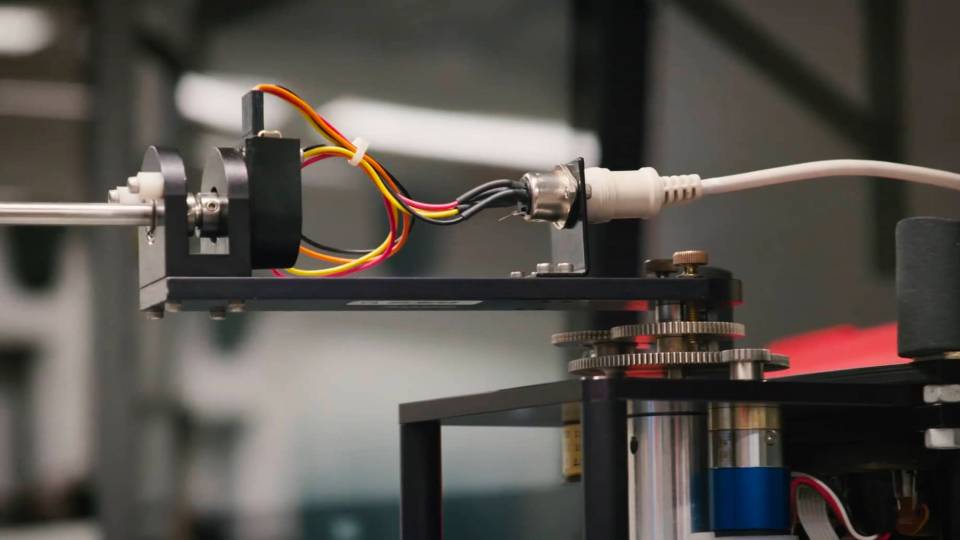

The nine students, working in two teams, led Nosenchuck down the wall of sticky notes, each corresponding with a project milestone, and told him each activity they plan to accomplish before their crucial May 15 deadline. That's when the teams must send their robots on a search-and-rescue mission as a final test. With software and hardware working in unison, the device must pick up and stow a medical kit and travel through a zigzagging narrow corridor. Then it must find a light, representing an injured person with a flashlight, travel toward it and place the medical kit into a narrow opening.

While the robots' job is to reach that light, the broader goal of the course goes back to those sticky notes on the wall. By adding a project management component into one of the core engineering design courses, Nosenchuck, an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering, aims not just to teach students better time-management skills but also to help keep them safe in their laboratory work.

The initiative, now being tested as a pilot, was the brainchild of Dale Grieb, the director of administration and services at the School of Engineering and Applied Science and the school's safety coordinator.

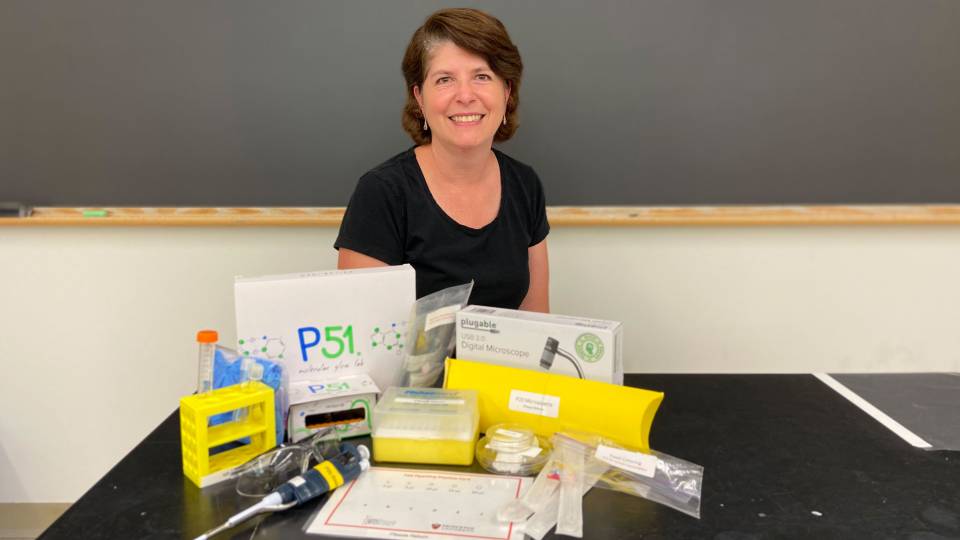

In a junior-level design course in mechanical and aerospace engineering, students (from left) Tarun Sinha, Hanna Eggers, Adlai Felser and Edward McClamrock set aside the hands-on work of building a sophisticated robot to focus on developing the project management skills needed to ensure the robot is built successfully and on time. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

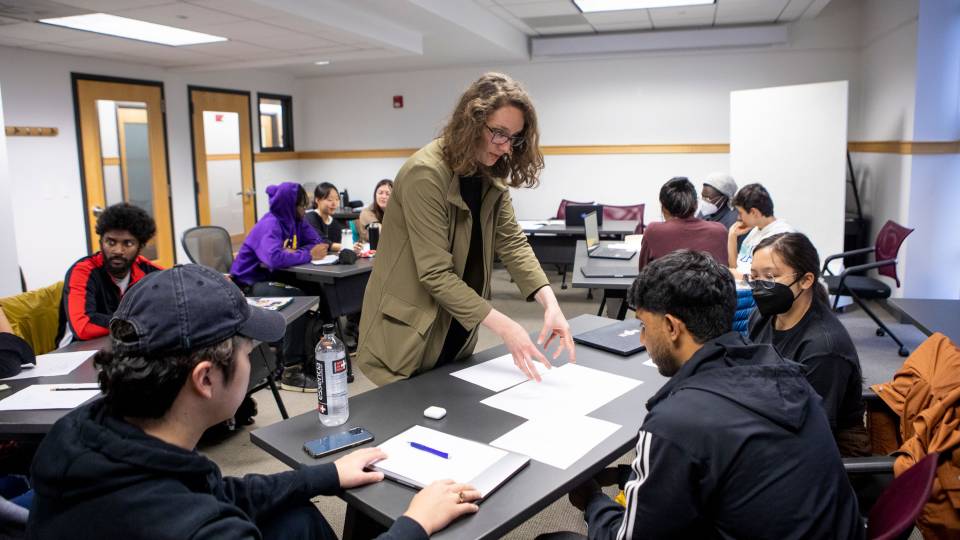

Grieb and Nosenchuck invited project management expert Frank Ryle to lead several class sessions and introduce students to the core principles of project management. At the recent session, Ryle gave the students the sticky note task to help them break their massive project into all of its small components in a visual way. He wanted to make sure they have realistic dates to accomplish each of their goals and that each member of the team knows exactly what he or she is supposed to do. He also asked them to include a few dates when they have social plans, such as the eating-club sponsored house parties on May 4, to help them make a more concrete connection with the deadlines.

Ryle, a consultant who has worked with companies in 22 countries and recently published the book, "Keeping Score: Project Management for the Pros," said seeing this kind of planning is crucial. "If it's in your head — our heads are messed up. We have overconfidence in our abilities. We see in a tunnel vision; we don't see the things that could go wrong," he explained. "Now they see all the work and the time they have to do it, and it just helps them to see the bigger picture, communally together. It's all this idea of prevention rather than the cure."

Independent consultant Frank Ryle (center) leads the students through project management exercises. The project management component of the course was the result of a collaboration between Professor Dan Nosenchuck, the School of Engineering and Applied Science and the Office of Health and Environmental Safety. The pilot initiative was created in part to improve safety and help avoid accidents for students using tools and machine shops for hands-on projects. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

The idea for the Princeton initiative was born in the aftermath of a tragic accident at Yale in April 2011 when Princeton and universities across the country tightened their safety protocols after a young woman working late at a machine shop died of asphyxiation when her hair was caught in a lathe.

Grieb worked with the Office of Environmental Health and Safety to establish new policies at Princeton requiring better lighting, limited hours and more supervision in the machine shops. But she still worried about the safety of overtired students using potentially dangerous equipment. "To me we were still at risk because we were not teaching these kids that design courses using tools are not courses you can cram for," she explained. "They have to be planned out."

Grieb, a University employee since 1971 who received the President's Achievement Award last year, brought her idea to her longtime colleague Nosenchuck, who was enthusiastic about enhancing the safety component of his design course. She even planned to teach some sessions herself. That part of her vision has not been realized because she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer shortly before the program began and has been in and out of the hospital ever since. But she is so excited about the course that she has continued monitoring its progress from her hospital bed via email.

"She's just been a real champion of this effort," said Garth Walters, director of the Office of Environmental Health and Safety. "If it weren't for her, it never would have happened."

Nosenchuck said he always advises students that their projects will take several times longer than they think, but formal project management brings that message home. When he reviewed the students' sticky notes, he tried to help students think realistically about the timeframe for each component. "That doesn't leave you much time," he warned one team. "Is there anything you can do to give yourself a buffer?"

Students use sticky notes to map out the steps and deadlines of their project, placing the notes along the length of a wall to create a walkable timeline that revealed potential challenges on the way to the final deadline. Hayk Martirosyan places a note while Gregory Hughes and Phyllis Schlafly look on. (Photo by Denise Applewhite)

Students said the techniques help them avoid the pitfalls of last-minute work and uneven work distribution among group members. "The single most important thing I've taken away is having a definite schedule," said Gregory Hughes, a junior. "It's hard for me to work hard on something without a definite schedule."

Phyllis Schlafly, a junior, said the crucial aspect for her was risk management. "With risk assessment you know exactly what could wrong,” she said. "It really defines that and makes the planning easier."

Ryle told the class that the business world has changed in the past decade and much more of the work is now project-based and crosses multiple boundaries — cultural, functional and global. "The ability to be able to organize and deliver 'a big thing' is highly valued in engineering and even in other nontraditional project-based organizations," he said.

Nosenchuck said he'd like to see the project management concept expanded to other design courses in engineering and maybe even throughout the University. "The methods of project management are broad, and simply intended to lead to a timely and high-quality conclusion to a task with a defined deliverable — be it creating an engineering design with a functional physical prototype, or performing research, say, in the humanities, and writing a thesis," he said.

The person who started it all says she shares his enthusiasm. "It's a dream come true," Grieb said of the pilot course. "I wish the project management course could be instituted at Princeton and that not just design students could take it."