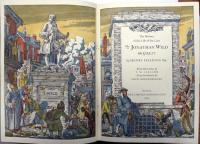

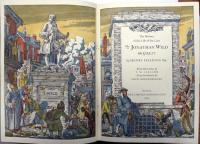

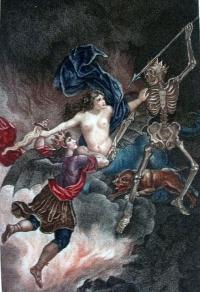

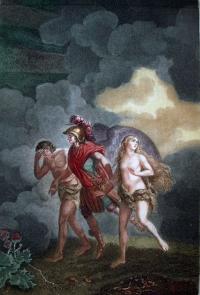

Henry Fielding (1707-1754), The History of the Life of the Late Mr. Jonathan Wild the Great. Illustrations by T.M. Cleland (1880-1964) and an introduction by Louis Kronenberger (New York: Limited Editions Club, 1943). Gift of Elmer Adler. Graphic Arts collection (GAX) PR3454.J663 1943

Soon after Thomas Maitland Cleland left school, at the age of 16, he taught himself to set type, bought a small Gally Universal, and began making books in his basement. In 1900, he moved to Boston and published under the imprint Cornhill Press, named after the street where he lived. D. B. Updike of Merrymount Press was an early mentor, who provided commissions and endless criticism, leaving Cleland chronically unsatisfied with anything less than perfection.

Cleland went on to work as art designer for McClure’s Magazine, the Locomobile Company of America, the Westvaco Corporation, the Cadillac Motor Car Company, and Fortune Magazine, although he wrote “I am not, and never have been, particularly interested in advertising and have done much of my work for it only because it was, or seemed to be, necessary in order to make a living.”

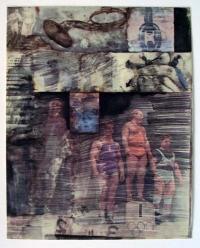

In the 1930s, he made a series of calendar illustrations for the Harris, Seybold, Potter Company of Cleveland Ohio, which manufactured high-quality sheet-fed offset lithographic printing presses. The company tried to convince the printing world that sheet fed-offset presses could produce quality 4-color process work and Cleland’s prints were meant to provide the proof. “God Bless America,” seen below, is one of these prints.

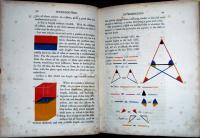

In between commercial work, Cleland illustrated fine press editions, often using a series of stencils. Writing to Merle Armitage about his process, Cleland explained “It is made entirely with stencils which I cut myself by hand in thin metal (thirteen of them in all) and which I then printed successively by brushing through them with pure water colours. … so far as I know, no one has attempted before to make a complete picture with them as a medium, and I hope no one will try it again. It was an insane amount of work for such a trifling result, and took about four months work to make a hundred of them—fifty for the special edition of Adler’s book of my work, and fifty for sale.” (GAX Oversize NE539.C57 A3 1929q)

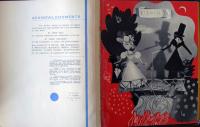

One of his most complex projects was Jonathan Wild, seen above, printed under Cleland’s supervision by the Marchbanks Press and published by the Limited Editions Club. In a letter to editor George Macy in 1942, Cleland wrote, “I am anxious to have this large line drawing photographed for the plate so … I should have proofs of the plate on which I can paint in the color for each stencil … so that they will have only the actual coloring of the edition to do after the book is off the press.” The coloring was accomplished by Charlize Brakely, who charged $10 per thousand pages. The book has 30 pages with color in an edition of 1,500, so that means a total of 45,000 pages to color.

Recent Comments