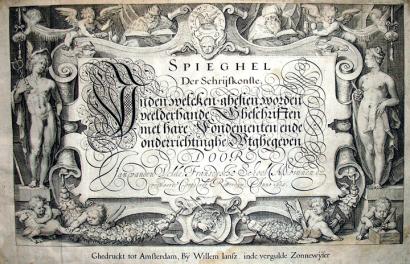

Jan van den Velde I (1568-1623), Spieghel der schrijfkonste (Mirror of the Art of Writing): in den welcken ghesien worden veelderhande gheschriften met hare Fondementen ende onderrichtinghe Wtghegeven (Amsterdam: Willem Iansz, inde vergulde Zonnewyser, 1609). 25 x 34 cm (oblong folio). Fifty-seven engravings including the engraved title page, an engraved portrait, and fifty-five leaves of calligraphic samples. *Note the putti pulling goose feathers to make writing pens.

Thanks to the assistance of the Friends of the Princeton University Library, graphic arts recently acquired a rare, complete third edition of this important Schrijfmeesterboek (writing-master’s book) from the Golden Age of Dutch art. Written and designed by Jan van den Velde I, this edition was printed by cartographic publisher Willem Janszoon Blaeu (1571-1638) with a title page cartouche designed by the artist and art historian Carel (Karel) van Mander (1548-1606) and engraved by the engraver and publisher Jacob Matham (1571-1631), along with fifty-five sample plates engraved by Simon Wynhoutsz Frisius (also written Vries, ca. 1580-1629).

The first edition appeared in 1605 published by van den Velde’s brother-in-law, Jan van Waesberghe II, in Rotterdam. The same year a second edition was published in Amsterdam by the printer and publisher Cornelis Claesz. The third edition was published by the no less famous printer Willem Janszoon Blaeu, after Blaeu acquired the original plates from the Claesz heirs. For an unknown reason, an extra plate by van den Velde has been added to this particular copy.

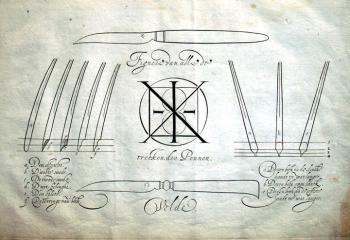

From the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries, two types of writing books predominated in Europe: the writing manual to offer instruction in how to make, space, and join letters as well as how to choose paper, cut quills, and make ink; and the copybook with engraved plates of writing models to be copied. Writing manuals and copy books are a top priority for library graphic arts collections, including Princeton University, to serve as a resource for the international study of letterforms.

Van den Velde’s volume is both a writing manual and a copy book, offering instructional texts as well as an extensive set of model plates with examples of all the different hands in use throughout Europe at that time. Written in Dutch, German, French, English, Italian, Spanish, and Latin, van den Velde not only covers the alphabets but also includes ornamental penwork confirming his dazzling mastery in the fusion of script with the calligraphic decoration.

As with many of these beautiful writing books, Spieghel is at once an artifact offering exceptional examples of high Dutch engraving and a research tool for undergraduate and post-graduate instruction in the history of letterform.

To his credit, van den Velde himself provides analysis as to the type of study his book would or should receive. In part three, he begins with a sustained discussion of the national hands that function both as treatise and manual, defining the criteria of mastering penmanship and diagramming, stroke by stroke, how different alphabets are formed. He justifies his reputation by noting that mastery consists not in specialization but in the ability of wield multifarious hands “I know well that what I teach here will be examined scrupulously by many fastidious souls, who will gravely proof my writing specimens as well, preferring to find fault rather than improve; I pray them to observe the good differentiation of hands before blaming the liberality of my pen, for though there will be those who have flown beyond the limits of my instruction, so they will find my book well governed, containing neither confusion nor scandal. Poets have their license, philosophers their exceptions, and painters their ornaments, so too with the pen, by degrees the quick and supple hand spreads its wings wider than that hand which writes an upright or heavy letter.” (Translated by historian Walter Melion in his wonderful article “Memory and the Kinship of Writing and Picturing in the Early Seventeenth-Century Netherlands,” Word & Image 8, no. 1 (January-March 1992))

Stanley Morison, writing in Calligraphy 1535-1885, commented, “The Spieghel’s format is of exceptional size. Van den Velde’s book is a magnificent specimen, not only with regard to the specific period it represents, but also in relationship to the entire history of calligraphy as an art. Of special note are the plates containing the Gothic letters, showing unique mastery in the fusion of the script with the calligraphic decoration.” Walter Melion wrote, “In scale, richness of ornamentation, and sheer number of specimens, the Spieghel is the most elaborate of these exemplaer-boechen.” Victor I. Carlson, in his essay for the Baltimore Museum’s 2000 Years of Calligraphy summed it up, “Van den Velde’s copy-book … is usually considered the most important work on calligraphy to be printed in Holland.”