April 10, 2002: Features

|

|

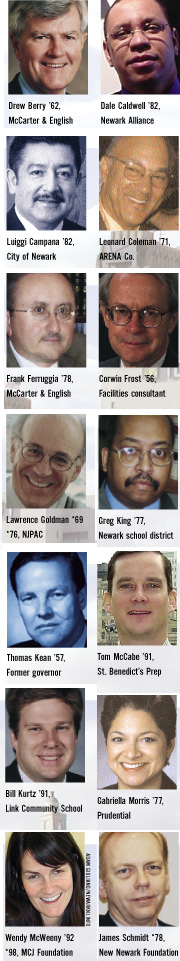

Princetonians work in every sector to bring the struggling New Jersey city back to life

By Argelio R. Dumenigo

Photo by Adam Giuliano/NewarkNJ.info

Newark, N.J. – Snipers and looters raced randomly from street to street through this city Saturday night. Tense national guardsmen and police, working under a state of emergency, fought to contain the fourth straight night of bitter racial violence.

— Los Angeles Times

July 15, 1967

Frank

Ferruggia ’78’s recollection is clear when it comes to the riots

that ripped through the heart of his hometown while he was a middle-schooler

growing up in the city’s West Ward. “I have memories of being

very frightened. We would have to show ID to get back into our neighborhood,”

says Ferruggia. “I remember hearing the sniper fire in the night.”

Frank

Ferruggia ’78’s recollection is clear when it comes to the riots

that ripped through the heart of his hometown while he was a middle-schooler

growing up in the city’s West Ward. “I have memories of being

very frightened. We would have to show ID to get back into our neighborhood,”

says Ferruggia. “I remember hearing the sniper fire in the night.”

Nonetheless, Ferruggia is still in Newark, a partner with McCarter & English, New Jersey’s largest law firm. He’s part of the effort to help Newark overcome the damage done by the 1967 riots, which were sparked by an incident of police brutality and led to 23 deaths and $10 million in property damage. For many Americans, a Life magazine cover photo of a child lying bloodied in the riot-torn streets became their lasting impression of the city.

“Had the urban disturbances not occurred, Newark would be a completely different city today. They essentially derailed the city for 25 to 30 years,” says Greg King ’77, a public information officer for Newark’s school district who recently moved back to the West Ward neighborhood where he grew up. “They transformed and transfixed the city into what it was to become and is now attempting to overcome.”

The slow rebuilding of Newark, New Jersey’s largest city, finally seems to be making real progress. The city now boasts one of the nation’s premier performing arts centers and a minor league baseball team, and has more than $2 billion in proposed school and downtown development on the horizon, including a professional basketball and hockey arena. And Princeton graduates are behind virtually every one of these renewal efforts.

“Do I think everybody comes out of Princeton having their heads turned just a little bit by Princeton in the nation’s service? Yes, I do,” says Drew Berry ’62, chairman of the executive committee at McCarter & English, whose headquarters in Newark’s Gateway Center sits across the street from where Berry’s grandfather’s street-cleaning business once stood.

McCarter & English was one of the few businesses that remained in the city after the riots, which spurred an exodus of jobs and a good chunk of Newark’s middle- and upper-class residents. According to the U.S. census, the city’s population fell from 405,220 in 1960 to 329,248 in 1980. The 2000 census put that number at 273,546.

Bringing those jobs and people back to Newark has not been easy, but things are improving, says Dale Caldwell ’82, executive director of the Newark Alliance, a consortium of executives from Newark-based businesses that offers consulting services to the city’s schools and government offices.

The son of a Methodist minister who has lived in several cities, Caldwell is a huge optimist when it comes to Newark. He sees a city that is a major transportation hub thanks to Newark Airport and Newark-Penn Station; a city with 40,000 college students courtesy of its Rutgers University campus and others; and a city considered one of the most wired in the Northeast corridor. “Newark has much of what it needs,” Caldwell says. “Not all of the financial resources, but a lot of the operational resources. There’s a lot of talent here in Newark, but it really needs help coordinating the talent and resources that are out there.”

Luiggi Campana ’82, the city’s assistant business administrator and a Newark homeowner since 1989, agrees with Caldwell when it comes to the infrastructure the city has maintained. “People have rediscovered Newark,” he says.

Campana, who was born in Ecuador and grew up in Connecticut, came to Newark to head ASPIRA, an organization dedicated to Latino education and leadership, and never left. He moved into City Hall when current Mayor Sharpe James took office in 1986.

While many people complain that the city’s development has been too focused on downtown, Campana counters that many neighborhoods have had empty lots replaced by housing units, both at public and market rates, and that much more is planned. “If you take the time to look at all the housing developments, you’ve got more than 5,000 new units in the last five to six years,” says Campana, who hopes that increases in government dollars will help further improve neighborhoods. In January, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development designated Newark a “Renewal Community,” making it eligible to share in an estimated $17 billion in tax incentives to stimulate job growth, promote economic development, and create affordable housing.

“If you go into the neighborhoods, you won’t see what you saw 10 years ago, or even five years ago. The development is incredible. And the average person who walks out there sees it, whether they see it downtown or whether they see it in the neighborhood,” Campana says.

Walking around in Newark was not a popular activity until 1996, when the New Jersey Performing Arts Center opened.

“You could’ve worked in Newark your whole life and never set foot on a city sidewalk. There was this fear factor that existed,” says Hope Blackburn ’81, former lead counsel for the Newark school district and now with the state education department. Blackburn came to Newark in 1995 with the state team that took over the city’s ailing public school system. “NJPAC wasn’t open when I got here. I would not have walked across Military Park then, but now I do it on a regular basis,” she says.

NJPAC was the brainchild of former Governor Thomas Kean ’57’s administration in the late 1980s. Kean, now president of Drew University, played a major role in getting the nearly $200-million center located in Newark, where it sits on the banks of the Passaic River.

NJPAC’s first employee was CEO Lawrence Goldman *69 *76, who has been credited with putting NJPAC in the company of Lincoln Center and the Kennedy Center. But as important as the high-quality performances put on inside the new center is the free summer music series NJPAC hosts outside. NJPAC has given Newark a scene where residents and visitors can take in “a slice of the city’s diversity in very mellow surroundings,” as Drew Berry puts it.

“Our objective was not just to build an arts center, but to rebuild a downtown,” Goldman explains.

Although the arts center is now universally cited as a catalyst for the city’s rebirth, there was plenty of skepticism about NJPAC before it was finished. Considering the anti-Newark sentiment in New Jersey and the failed projects Newark residents have faced over the years, it was probably warranted. “There have been lots of undelivered promises in Newark. NJPAC was a delivered promise,” says Goldman.

When Goldman arrived at NJPAC in 1989, he began by visiting cities such as Cleveland and Pittsburgh, which had to overcome the loss of industrial jobs that Newark felt in the 1970s and 1980s. Goldman then set about hiring some of the top planners in the country to design the building.

“There’s hardly a renowned artist in any field, jazz, dance, classical music, theater, who has not been through our theater or orchestra,” Goldman boasts. “It’s another example of what makes cities great. Why do people go to London, or Greenwich Village, or Soho? For a diverse, exciting, stimulating, edgy experience that you can’t get in the Short Hills Mall.”

Two other big pieces of the renewal of Newark’s downtown are still in the planning stages: a $180-million real estate development that would bring market-rate housing, retail stores, and 1,100 parking spaces to the city, and a 20,000-seat arena for the NBA’s New Jersey Nets and the NHL’s New Jersey Devils. Princeton graduates lead both proposed projects.

“Who would have thought you’d find pioneers in Princeton?” jokes architect and urban planner James Schmidt *78, executive director and CEO of the New Newark Foundation, the nonprofit organization that is overseeing the real estate development project.

Like Goldman, Schmidt investigated what has been done in other cities where redevelopment has been successful, including Philadelphia and Chattanooga. He also hired planners and developers who had the experience and know-how in rebuilding urban areas. Where visitors and downtown residents see empty buildings, Schmidt envisions a 24-hour community, with mixed-use housing and shops and attractions that invite people who work downtown to linger after hours.

“If there’s a moment for Newark, this is it,” says Schmidt, who hopes to break ground on the project in 2003. “People in Newark are tired of empty buildings. They’re tired of having to go to Woodbridge to shop. For the people who have been in our neighborhoods hanging in, it will be a great benefit.”

On the arena front, Leonard Coleman ’71 is leading

the push as chairman of ARENA Co., the YankeeNets unit working to build the Newark arena. In response to the inevitable questions about the actual economic benefits a sports arena brings to an urban center — as cities, counties, and states argue over using tax dollars to fund playing areas for millionaires — Coleman delivers a solid answer: 12,000 jobs.

Coleman — who is the former president of baseball’s National League and has been involved in Newark since his undergraduate days, when he worked in the office of former Newark councilman Calvin West — and other arena backers foresee more than just an arena. They are proposing a 4.3-million-square-foot district that will include office, retail, hotel, restaurant, entertainment, and residential space. Although there has been much wrangling at the state, county, and local levels over who will pay the arena’s $355-million price tag, Coleman says he is “very positive we’ll get it done.” He believes the arena would spur further development. “I’ve seen what happens in communities where new ballparks and arenas have been built,” he says, citing Denver and Baltimore as examples. “It’s emotionally uplifting. There’s a sense of pride in having professional sports in a town, there’s no way around it.”

Fellow arena proponent Wendy McWeeny ’92 *98 says that the arena will truly be community-based, from the job training and apprentice opportunities the construction project will provide to a proposed health clinic to be located on-site. “You can leverage the arena as an economic engine,” says McWeeny, who works for the MCJ Foundation, a philanthropic organization dedicated to the revitalization of inner-city neighborhoods started by Newark native Ray Chambers, who is part owner of YankeeNets.

McWeeny recalls childhood visits to Newark’s Ironbound – the largest Portuguese enclave in the U.S. – with her father, McCarter & English’s Drew Berry, but she still says she feels like she’s “jumping on the bandwagon” in Newark’s revitalization efforts.

Trendy or not, McWeeny’s work with the Newark board of education to recruit and retain top-notch teachers will go a long way toward rebuilding one of city’s sorest areas. Seven years ago New Jersey officials decided to take on the failing test scores, bloated administration, and mismanagement that characterized the 45,000-student Newark school system. The district’s budget hovers around the $600-million mark.

Since then, the state has encountered its own problems, including a $73-million shortfall two years ago, continuing poor test scores, and a $1.6-billion school facilities building and renovation program that has yet to get off the ground.

McWeeny, who is loaned out as a consultant by MCJ, has been working with the district on the possibility of creating a teachers’ residential community that could help in attracting qualified teachers. Getting those teachers and fixing the schools will play a big role in getting Newark over another great hump: holding on to the working- and middle-class families who want their kids to go to good schools.

Frank Ferruggia lived in a palatial, 14-room house in Newark’s North Ward near Branch Brook Park – a Frederick Olmsted-designed park – with his wife and three children until he made the wrenching decision to move to the suburbs because he wanted a better school system for his kids. “As far as making a home and raising a family in Newark, the schools are still an issue,” says Ferruggia.

Newark is one of New Jersey’s Abbott school districts — 30 of the state’s poorest districts covered by a 1997 state court decision that calls for state money to be used to balance out the financial and educational inequities between affluent suburbs and poorer urban and rural areas. New Jersey has only recently started doling out the money for $6.8-billion worth of projects statewide, including a $1.6-billion building project designed to replace 34 Newark schools, build nine new ones, and renovate an additional 30. Facilities management consultant Corwin Frost ’56 oversees the Newark project.

Frost arrived in 1995 after the state’s takeover of the city’s schools. Years of use and growing enrollment had worn the buildings down, leading to high maintenance costs and no room for programs such as music, art, and lab sciences. Frost believes the new and renovated schools will serve as physical and social catalysts for their neighborhoods and eventually keep families from leaving, and he hopes the first buildings in the project will be open by 2005. The entire project will take at least 15 years, he says.

“A dilapidated old building with graffiti problems is a turn-off. People don’t want to send their kids there,” says Frost, who oversaw the overall planning and design of all 20 City University of New York campuses before coming to Newark.

Frost met with many Newark residents as the school district pitched its facilities plan. He says their initial wariness and disillusionment has been replaced by a better attitude. “It’s starting to dawn on them that it could happen.”

One school that has not had to worry much about its facilities is St. Benedict’s Prep School, where Tom McCabe ’91 has worked since he walked out FitzRandolph Gate. In that decade, Benedict’s has benefited from the donations of wealthy alumni, who have helped turn the school into an athletic and academic oasis in Newark’s Central Ward, which was hardest hit by the riots. Most of the students at the parochial all-boys school come from the city, says McCabe, now assistant headmaster and director of college guidance.

“When everyone says you can’t educate the children in Newark,” says the Newark Alliance’s Dale Caldwell, “Benedict’s shows you it’s not true.”

McCabe says that success comes from having high expectations of the students, making them responsible for their actions, and filling their day with activities, including a diverse sports program. With the crime, drugs, and negative attitudes that permeate some of his students’ lives, McCabe calls the school a “counterculture operation.” His eyes beam as he talks about the school (whose history he is researching for his Rutgers, Newark doctoral dissertation), the city, and the students, two of whom are now at Princeton.

“People tell me, ‘With a Princeton degree you could be doing anything,’ ” says McCabe. “What I do here, though, this is needed work, important work.”

McCabe’s former Princeton floormate, Bill Kurtz ’91, is now his neighbor in Newark as well. Kurtz is principal of the Link Community School, one of the city’s top middle schools, which is also in the Central Ward. Recent statistics from the 128-student school far surpass Newark’s overall numbers: 100 percent of its 1997 graduates went on to graduate high school, compared to the less-than-50 percent graduation rate for the city as a whole.

Kurtz, who earned a master’s degree in educational leadership at Columbia, grew up in Maine and did not know much about Newark, aside from the airport, before he arrived. He originally intended to start his own charter school in the city, which now has a dozen of the quasi-public schools. School district funds cover about 85 percent of the charter schools’ budgets. But in Link, a private, nondenominational school that uses a sliding tuition scale to allow low-income students to attend, Kurtz found an existing school that provided him with the opportunity he was seeking.

“The community is defined by its vacant lots instead of by what else is here,” says Kurtz. “The families we serve have been underserved and see no opportunities just because they live in Newark. Link is about giving people opportunities.”

Kurtz, who studied Third-World development as part of his senior thesis, cites Newark’s low high school graduation rates and its high infant mortality rate, which is twice the state average, as he discusses the level of problems the community is facing. “When you have a graduation rate of 40 percent, it’s clear you’re not going to make a dent in your economic cycle. You end up with people with very little economic mobility,” says Kurtz, who would like to see more invested in neighborhoods. “I see decisions that are made by the public sector that the private sector perpetuates. The private sector can do a better job of demanding change and the results that kids deserve in this city.”

Gabriella Morris ’77 plays a significant role with one of the city’s major private sector benefactors, Prudential. As head of the insurance company’s community resources division, Morris focuses her attention on education, workforce development, and economic development in Newark, Prudential’s headquarters. In recent years, Prudential CEO Art Ryan brought back sections of the company that had moved out of the city. About 5,000 people now work for Prudential in four buildings downtown.

The company has not only played a major role in big developments, such as NJPAC, New Newark, and the Newark Alliance, but through the Prudential Foundation has also funded hundreds of local efforts to improve the community.

“There’s a misconception about redevelopment in Newark. It’s not just a downtown story. It’s a neighborhood story,” says Morris.

She cites education, civic engagement, and job creation as the three main issues that Newark has to address before really turning the corner and improving the quality of life for its residents. Like the other Princeton “urbanists” in Newark, she realizes that it is not a simple task to bring back a city.

“The rise, fall, and rise hasn’t happened yet. That’s

what we’re working on, we’re working on history,” she says.

![]()

Argelio R. Dumenigo is associate editor of PAW.