November 20, 2002: Features

Obsessed with the details, Robert Caro ’57 turns history into a great read

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83

Above: Robert Caro ’57 in the Russell Senate Office Building, where he soaked up the atmosphere for Master of the Senate, the third of a four-book biography of Lyndon Johnson. (© 2002, The Washington Post. Photo by Bill O'Leary. Reprinted with permission)

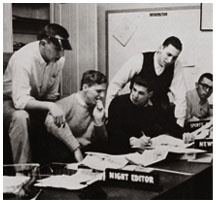

Right:

In the press room at the Daily Princetonian in 1956. From left, William

Greider ’58, Robert Bolgard ’57, Caro, Norton Rosensweig ’57,

Alan Graber ’57, and William Rosenblum Jr. ’57. (princeton university

archives)

Right:

In the press room at the Daily Princetonian in 1956. From left, William

Greider ’58, Robert Bolgard ’57, Caro, Norton Rosensweig ’57,

Alan Graber ’57, and William Rosenblum Jr. ’57. (princeton university

archives)

Below: Caro in his office, in front of his wall-chart chapter outlines for Master of the Senate. (joyce ravid)

Hour after hour, Robert Caro ’57 sat in the ornate gallery of the United States Senate and watched. Day after day, the tourists would file in, stay for a few minutes, then shuffle back out again. Still, Caro sat. The business of the Senate droned on, the endless quorum calls, the requests for unanimous consent, the seemingly arcane parliamentary back-and-forth.

And still Caro sat, enrapt.

Someone once compared baseball to church, saying, “Many attend but few understand.” The same might be said of watching the Senate of the United States in action. Caro attended, and finally, after a time, he understood as well.

“To the tourists and the guards at the door, I was the nut in the gallery,” he recalls with a smile. “Sometimes I felt almost as if the Senate was putting on this show for me, that the Senate of the United States was here showing me how it worked.”

What Caro came to understand were the nuances of legislative power, nuances he brought to life in his most recent book, Master of the Senate, the third volume of a projected four-part biography, The Years of Lyndon Johnson, that has occupied him for more than a quarter-century. In it, Caro chronicles Johnson’s Senate career, which culminated in passage of the landmark 1957 Civil Rights Act and also changed the institutional structure of the upper chamber in ways that can still be seen today.

But being “the nut in the gallery” was only a small part of the 12 years it took to produce Master of the Senate, which was published in April. In a story that has already become famous among Caro devotees, he persuaded former Senator Bill Bradley ’65 to take him onto the Senate floor one day and stand at the majority leader’s desk, the better for Caro to judge how the six-foot-three-inch Johnson would have towered over his colleagues. While working on the first Johnson volume, The Path to Power, published in 1982, Caro convinced his wife, Ina, to move to the Texas hill country so he could try to understand the nature of the land that shaped L.B.J.’s character. During the three years they spent there, Caro waded through documents in the L.B.J. Library by day and then headed out each evening into the vast, empty country to track down those who knew Johnson in his youth. He dug his hands into the thin topsoil so he could feel how hard it was to eke out a living there. To heighten his sense of the area’s loneliness, he even brought along a sleeping bag and spent several nights in the deserted hills.

Favorable reviews continue to pour in for Master of the Senate, which has been nominated for a National Book Award. In addition to generally glowing reviews in the U.S. and a spot atop the New York Times bestseller list, the book recently was published in Great Britain, where it has been hailed in reviews as one of the best studies ever made of the American legislative process. “Robert Caro has written one of the truly great political biographies of the modern age,” wrote the London Times.

It is a combination of scholarship and readability that has earned Caro a place among America’s preeminent historians. The Power Broker, his 1974 book about New York Parks Commissioner Robert Moses, won the Pulitzer Prize for biography as well as the Francis Parkman Prize, awarded by the Society of American Historians to the book that “best exemplifies the union of the historian and the artist.” Modern Library named it one of the 100 greatest books of the 20th century. The first two volumes of his L.B.J. series each won the National Book Critics Circle Award as best biography of the year.

“When I started to write The Power Broker,” Caro says, “I wanted to write it on the same level as great literature. And as time has passed, I’ve come to believe that a work of history that endures does so because the writing, the level of the narrative, the words, are the same as in great fiction.”Depth in the details

Caro’s insistence that the prose matters and his relentless pursuit of the last, telling detail to support that prose, both manifested themselves during his years at Princeton. Though he jokes that he decided on Princeton after attending houseparties, his friends remember him as a serious and very private young man. Having edited his high school newspaper at New York’s Horace Mann School, Caro joined the Daily Princetonian, one of a remarkable journalistic class that also included R. W. Apple Jr. ’57, now chief correspondent for the New York Times.

“Each of them had somewhat of a strong personality,” recalls Richard Kluger ’56, a Pulitzer Prize-winner himself, who served as chairman of the Prince during Caro’s junior year. “Neither was notably modest. But their gifts were clear.” Even so, Caro’s tenacity stood out.

“He was certainly the most dedicated person there among a lot of other dedicated people,” recalls John Doyle ’56, Caro’s predecessor as managing editor.

Caro was a prolific writer at Princeton — perhaps more prolific, he now concedes, than insightful. In addition to writing news and feature articles for the Prince, Caro wrote a breezy sports column titled “Ivy Inklings.” He also wrote for the Nassau Literary Magazine and contributed one short story that consumed almost an entire issue of the Tiger. His senior thesis, on Ernest Hemingway, was 235 pages long.

“I was always writing,” he recalls. “I wrote these very long stories, but I was always doing it the night before they were due. I could always write very fast. I thought I was so great.”

Literary critic Richard P. Blackmur, a member of the Princeton English department, gave Caro a somewhat different evaluation that changed his life. Although Blackmur complimented Caro on his work, he added, “‘You’re never going to achieve what you want to achieve, Mr. Caro, because you think with your fingers.’”

Being indicted as a facile writer hit Caro hard. “Did you ever know when someone has really seen right through you?” he asks, still abashed at the memory. “Because I never thought. I just wrote.”

It was Carlos Baker, longtime chairman of the English department as well as a renowned Hemingway scholar and Caro’s thesis adviser, who taught him the importance of language, of le mot juste.

“One thing Baker used to say — it stuck with me all my life — is that Hemingway tried to find the thing that created the emotion,” Caro recalls. “And he made me understand that there is a best word. Sometimes, if you saw me writing, looking for an adjective, I might list a dozen adjectives looking for the right one. I think if you do that, you will be repaid personally because your books will endure, and you will be doing something for history because you will make people see what things were really like.”

That insistence on capturing the detail that creates the essence of a moment was further sharpened during his years as an investigative reporter. Caro joined the New Brunswick Home News after college and moved to Long Island’s Newsday a few months later, where he won numerous awards. He credits his editor, Alan Hathway, an old Chicago newspaperman who might have stepped out of Ben Hecht’s The Front Page, with teaching him how to interview. “You’re not there to let him tell you what he wants to tell you,” Hathway would yell about some Long Island politician Caro was covering. “You are there to find out what happened.”

While on a Nieman Fellowship at Harvard in 1966, Caro decided to take a leap and left Newsday to write The Power Broker with only a $5,000 advance to sustain him. The Caros sold their house on Long Island and moved into an apartment while Ina Caro taught school to help support the family, which included a young son, Chase ’82. After several very lean years, Caro eventually received a larger advance, as well as a Carnegie Fellowship, which enabled him to finish the book.

“I loved being a reporter, but one thing I hated was always having to write while you still had questions,” he says, explaining his decision to write books. “They would give you a week, occasionally they’d give you a month, but at the end of the month I’d always have more questions. So when I started The Power Broker, I told myself I was not going to write it until I felt I had learned all I could.”

What the biographer must find, Caro believes, is perspective. “While there is no absolute truth, there are an awful lot of objective facts. And the more of them you find out, the closer you come to whatever truths there are.”

As Caro says, there are an awful lot of objective facts. The Power Broker, which took seven years to complete, is 1,162 pages long, and that only after Caro was forced to cut 300,000 words in order to fit it into one volume. The Path to Power, which took another eight years, is 768 pages long. After writing Means of Ascent, the second and shortest of the Johnson books, in only eight years, it took him another 12 to produce Master of the Senate, which runs 1,040 pages.

In the quarter-century he has been working on the L.B.J. series, Caro has conducted hundreds of interviews, much of it groundbreaking work with old Johnson friends and associates who never had spoken to a reporter or historian in such detail. His typed and handwritten notes from those interviews (he eschews computers and writes all his books in longhand) fill two filing cabinets in his Manhattan office. A Caro interview can last for hours and is rarely completed in one sitting. If interviewing three people who participated in a White House meeting, Caro explains, he starts with the printed minutes of the meeting, if they exist, then interviews each participant individually. Once that is done, he may go back for further interviews to clarify points, flesh out details and, if need be, challenge each with what the others have said. Slowly, painstakingly, a complete picture of what happened emerges.

Nevertheless, memories of the Johnson years are fading and Caro knows he is in a race against time. He still remembers talking two decades ago to former Supreme Court Justice Abe Fortas, Lyndon Johnson’s consigliere through much of his career. The two agreed to meet each Thursday in Washington for interviews. At their first meeting, Caro asked about a particularly important event and Fortas replied, “Oh, that’s the right question. We’ll talk about that next Thursday.” The following week, Caro picked up a newspaper and read that Fortas had died, taking the answer to that “right question” to the grave.

“I felt,” he says, “as though someone had punched me.”

The writer’s craft

But the process of making one of Caro’s books is much more laborious than even those nights under the South Texas stars might suggest. For every day spent on the Senate floor with Bill Bradley or sitting down with Abe Fortas, there might be a hundred alone in the archives, just Caro and the boxes. There are 2,082 of those boxes in the L.B.J. Library comprising more than 1.6 million pages, dealing just with Johnson’s Senate years, and Caro is determined to peruse as many as he can.

“I can’t tell you the number of times I found a crucial piece of information written on the back of some other piece of paper,” he explains.

The boxes in the L.B.J. Library are only a start. Caro and his wife, his only research assistant, must wade through thousands of other boxes, containing the papers of other presidents, public figures, and journalists, in dozens of other libraries around the country. Then there are the newspapers. For Master of the Senate, Caro read almost every issue of the New York Times, the New York Herald-Tribune, the Washington Post, and the Washington Star covering the years in question, as well as newsmagazines and other periodicals. It is a tedious process, scrolling through roll after roll of microfilm, a frame or two at a time, taking notes.

“People ask me why it takes so long,” Caro remarks about his books. “That’s why.” Once he has completed the bulk of his research, Caro returns to his office and begins an outline. He starts with a brief summary of what the book is to be about, a page or less, which he next fleshes out to about 10 pages. From there, he slowly adds detail upon detail until the outline fills a shelfful of loose-leaf notebooks, their pages marked with colored notations to the particular interviews or documents that support each point. The outline pages for the chapter on which he happens to be working are pinned to a corkboard behind his desk, the margins often filled with editorial side notes to himself.

Caro’s massive outlines cover more than just facts, dates, and arguments. He composes the book in his head as he goes, leading off each outline heading with the transition sentence he will use to push the narrative along. “I can’t start the book until I know what the last sentence is,” he explains. “I have to be able to see the entire book before I start.”

After all that time researching and organizing, how does he know when it is time to start writing? Caro takes a long pause.

“It’s when you don’t have any more big questions,” he answers at last. “Up to that point, it’s been a very different life — you’ve been doing interviews, traveling all around the country, living in Washington, going over to the Senate, going over to the library. And then that ends, and now you’re going to sit here for three or four years.”

Though the process of choosing his words can be difficult, Caro has the rare ability to go straight to his desk in the morning and get to work, something he credits to his experience as a journalist. After discovering that he was usually dissatisfied with pages written late in the afternoon, he now tries to stop writing after five hours. Like his hero, Hemingway, Caro keeps track of the number of words he writes each day and cites the novelist’s dictum that a writer should quit when he knows what his next sentence is going to be.

To Caro’s critics, many of whom are academic historians, his emphasis on description and atmosphere occasionally smacks of melodrama. Sidney Blumenthal wrote a long essay in The New Republic shortly after Means of Ascent was published, accusing Caro of sacrificing historical accuracy for drama in his treatment of Coke Stevenson, Johnson’s opponent in the 1948 Senate race. (Caro vigorously denied doing so.) Stanley Kutler, professor emeritus at the University of Wisconsin, predicted in the Washington Post last spring that while Caro’s book will sell “oodles of copies . . . 20 years from now it won’t be used by scholars writing about Johnson.”

Not surprisingly, Caro takes exception.

“I think it’s very unfortunate — this divide between academic historians and historians whose backgrounds in many cases are in journalism,” he responds. “Because I think that the best popular historians are just as rigorous in their demands for proof. Academic historians don’t seem to fully realize how much the writing matters. Parts of history are very dull, but parts of history are quite thrilling. So you’re not really being true to history unless you do everything you can to make it just as exciting on the page as it was in real life.”

Sean Wilentz, Dayton-Stockton Professor of History and Princeton’s director of the Program in American Studies, has criticized Caro’s first two Johnson books as strident and one-dimensional, calling them, in one published review, “relentlessly abusive” of Johnson and a “defamatory depiction of Johnson’s early career.” Nevertheless, Wilentz takes pains to praise Caro as a historian.

“Caro is an absolutely demon researcher who believes in and manages to have the energy to obtain every scrap of information about his subject,” Wilentz says. “He also has a great ability to dramatize his subject. There’s always something new in everything he writes.”

Wilentz thus distinguishes between lucid yet original works of history, like Caro’s, that deservedly sell well, and what he calls the “costume-drama Americana” and “blockbuster historical epics” of popular writers such as David McCullough and filmmaker Ken Burns. The former, he says, can serve to instill an appreciation for history in readers who might have been repelled by the dry fare frequently taught in schools.

“Well-written, strong history is a good thing,” he adds. “I wish my books sold as well.”

New project at 67

His book tour and signings now over, Caro will soon return to Austin, to the L.B.J. Library, and begin to dig again, embarking on the still-untitled fourth and final volume of the Johnson series, which will cover the tumultuous years of his vice presidency and presidency. Caro says he also plans to spend time in a small Vietnamese village in order to understand how the projection of American power abroad — in this case, bombs —affected the powerless.

At age 67, when most of his classmates are either retired or planning to wind down, Caro has lashed himself to a project that will probably require another decade of work. Although he estimates that the next book will take only five years, he concedes that he has been notoriously inaccurate on such predictions in the past.

But will historians still be citing him 20 years from now? Caro tells a story about the New York Coliseum, which Robert Moses built in 1956 at Columbus Circle, just around the corner from where Caro now has his office. The Coliseum, Moses predicted, would make him immortal. The Power Broker appeared while Moses was still alive, and he frequently disparaged the book and its mixed appraisal of him. Almost 30 years later, Caro’s book remains on the shelves, while the Coliseum was demolished two years ago.

“That’s what [Moses] used to say,” Caro tells with a certain relish. “‘How long will The Power Broker last? It’ll be gone before you know it.’ So when they started tearing the Coliseum down, that was one of the greatest moments of my life!

“Books do last.” ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 recently published Football: The Ivy League Origins of an American Obsession (University of Pennsylvania Press) and is working on a book about the electrification of New York.

For an interview with Robert Caro ’57, go to PAWPLUS at www.princeton.edu/paw/plus.