Assembly

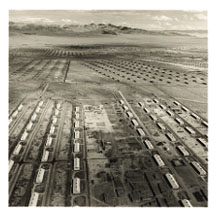

Buildings and Munitions Storage, Hawthorne Army Depot, Nevada, 1988. From

Emmet Gowin’s Changing the Earth.

Assembly

Buildings and Munitions Storage, Hawthorne Army Depot, Nevada, 1988. From

Emmet Gowin’s Changing the Earth.

This month, you can walk into 185 Nassau Street and view photographs, paintings, ceramics, and other work created by students in Princeton’s visual arts program. The projects, on display through February 25, represent the best work of young people still coming to terms with their art, their subjects, and themselves.

Some 25 years ago, photographer Andrew Moore ’79, whose pictures of Havana are featured in this issue, was one of these students, studying under Emmet Gowin, among others. Today, the two men are colleagues, Gowin serving as director of the visual arts program; Moore, a visiting professor.

Princeton’s photography program is both nurturing and demanding. Competition for the first-year classes is tough; instructors sometimes interview 50 students for each class of 12. Gowin doesn’t seek out the best technical skills, or the most successful records. He wants young artists who can embrace openness and be able to fail. The goal, he says, is to bring together the mind, the heart, and the hand.

Today, as when Moore was a student, Gowin and other instructors push young photographers to supplement their liberal arts studies with something more: a willingness to take risks, to expose themselves, to place “mystery in equilibrium with intellect.” In that way, Gowin says, the personal becomes universal. “It is,” he says, “why culture needs art.”

That’s what Moore accomplished in his Havana photographs, collected in a volume called Inside Havana (Chronicle Books). He shot once-elegant facades now rotting away, and painstakingly maintained interiors that speak from another age. The spaces embody the people who live within them, and the intimacies of their lives tell a larger story.

A collection of photographs by Gowin, meanwhile, is being exhibited across the country and in a book, Changing the Earth, which was published recently by the Yale University Art Gallery and Yale University Press. The photographs are simultaneously horrible and beautiful: black and white aerial images of strip mines, toxic water treatment facilities, massive farming operations, military test sites. They show scars, tracks, and craters – and, at the same time, fascinating patterns, shapes, and light. Devoid of people, each one tells a human story. Photo-graphed from afar, each one is intimate.

“These things are all handmade,” Gowin says. He recalls the first time he “had to reconcile the horror and the beauty,” when he began to print photographs from the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Washington State.

But “the slant of the October light does not regret human error,” he says. “When the light strikes the ground and makes it beautiful, it still shocks us. In a way, it is sad, tragic, and hopeful, all together.”

At 185 Nassau Street, we watch as young artists learn these lessons,

too. ![]()

![]()