October 22, 2003: Features

As soldiers, journalists, relief workers, and policymakers, Princetonians have been intimately involved in events unfolding in Iraq. Here, some tell their stories.

In

a flash, confidence vanished

In

a flash, confidence vanished

By Joshua Hammer ’79

Joshua Hammer ’79 is chief of Newsweek’s Jerusalem bureau.

When I flew into Baghdad from Amman August 12, three months after my last tour of duty in Iraq for Newsweek, I was surprised to see how the capital had changed.

Despite the torrent of stories about the absence of security and a worsening guerrilla war against Coalition forces, there were unmistakable signs of recovery. In contrast to the blasted-out, moribund city I had left in late May, Baghdad was humming with commercial activity; restaurants were open, looted shops cleaned and restocked, streets jammed with vehicles, markets overflowing with everything from Toshiba laser disc players to granola breakfast bars. Sure, Baghdad’s power stations still provided juice for a maximum of six hours a day, forcing Iraqis to swelter in un-airconditioned apartments in the 125-degree summer heat, and occasional bursts of gunfire rang out around my hotel, reminding me that crime and instability were indelibly etched in the fabric of life in Iraq. But, preparing to write about America’s misguided mission, I found myself slowly succumbing to U.S. chief administrator L. Paul Bremer’s soothing assurances in his weekly press conferences that Iraq’s recovery was on track.

Then, in a flash of light and smoke, that confidence vanished. On August 19, I had just returned to my office at the Al-Hamra Hotel near the river, back from a grueling day interviewing engineers at the al-Daura power plant for a story on electricity, when a Newsweek photographer phoned the bureau.

“A bomb just exploded at the U.N. headquarters,” he told me. “Better come quickly.” I jumped into a car with my Iraqi driver and interpreter and headed east through Baghdad’s

traffic-clogged boulevards toward the U.N. at the Canal Hotel, a half-hour drive away. Traffic patterns were normal, and I began to doubt the veracity of the report; then I saw a long line of U.S. military helicopters sweeping low across the sky and smoke rising from the hulking brick-and-stucco edifice. I drew in a breath; I had made an appointment for an interview with U.N. officials at the Canal Hotel a few hours earlier, only to have had it canceled at the last minute.

A tank filled with U.S. troops blocked the main road leading to the headquarters. “We have orders to let nobody pass,” a soldier told me. “We’ve got to keep the street clear for ambulances. Massive casualties.” As I continued on foot down an alley out of sight of the American soldiers, I came upon a handful of bloodied survivors drifting out of the compound. “Sergio is buried in the rubble,” one of them told me, sobbing, referring to U.N. special envoy Sergio Vieira de Mello.

I knew at once that this was a major disaster, a huge setback for the

U.S. reconstruction effort and Middle East policy, a story that would

resonate long after the bodies had been buried and the rubble cleared.

![]()

The

missing man

The

missing man

By Tally Parham ’92

PHOTO: Tally Parham ’92, now back at her law practice, piloted F-16s over Baghdad.Tally Parham ’92, an attorney in Columbia, South Carolina, flies F-16s as a captain in the South Carolina Air National Guard. Parham was based in Qatar during the war in Iraq, and was demobilized in June.

At first we didn’t understand why such time and money were expended erecting shiny, towering flagpoles in the middle of our air base in Qatar. An airman swept the smooth marble foundations clean, and the poles’ 30-foot-plus majesty stood in ridiculous contrast to the rest of the worn, dusty, hastily installed camp. We could imagine many things that might have improved our lifestyle and morale, but the luxury of gazing up at four Coalition flags flapping in the harsh breeze was not one of them. The tents we slept in were cramped and torn; the rudimentary sewage system seeped a disgusting smell everywhere. Better food, new F-16 parts, more laser-guided bombs – we could use them all, but not this.

It was nearly 3 a.m. in Qatar. In spite of my earplugs and Ambien-induced sleep, I woke up when they came through the wooden door to get Nikki. She slept only a few feet from my head, across the aisle of our tent. She was the most thoughtful and considerate of my 12 tentmates. The little shamrocks or chocolate bunnies she left on our pillows reminded us that back home it was some holiday. She brought us “Dear Soldier” letters written by Girl Scouts from her hometown, and gave us their addresses to write back. In spite of the stress, she was never irritable. Not even after her airman husband disappeared.

At first, he had not been scheduled to fly that night. Someone dropped out of the schedule, and Nikki’s husband, Boot, was the backup. He was, as always, thrilled at the chance to fly. I remember how excited Nikki had been when she found out that he was going to be deployed to our base – a miracle, since she was an intelligence officer in a different squadron. Boot was Nikki’s match in grace and kindness, and a superior F-15E pilot. All she found out at 3 a.m., and all she would know for the next excruciating week, was that soon after he dropped his last laser-guided bomb, an explosion erupted larger than any other that night. Was it his jet hitting the ground, or a secondary explosion? The weather was bad. Neither he nor his back-seater answered their radio check-in. No emergency locator beacon was heard. No one knew if they had had time to get out of the jet.

Though she must have feared the worst, Nikki told herself that Boot had ejected before impact, and that his emergency locator beacon was turned off so that Iraqis would not find him before a rescue team could. Of course, that’s what I believed, too. It was natural for those of us flying nightly over Baghdad to assume the best – our Teflon self-images would not permit doubt to stick. Whether the threat was barrage anti-aircraft fire, a lucky SAM launch, engine seizure, or a fuel leak – we had a contingency plan for everything, even the route we would use to evade capture. Her private struggle was an uneasy reminder of our own mortality, and the impossible chance that we might subject our own spouses to grief.

The next day I was scheduled to fly a sortie far north of Baghdad, where the F-15E presumably went down. The layer of low clouds that day removed any impulse to look for the crash site. It wasn’t our mission to do so, anyway. The area under us was still controlled by the Republican Guard, so there would be no easy “investigation” anytime soon. Our sortie was uneventful: We dropped our bombs, shot our missiles, and went home.

Days later we wearily shuffled back to camp from a nightlong sortie,

our raw eyes burning in the dawn. Hearing the flags whipping in the dusty

wind we looked up. In one instant we knew that Boot had been found, enough

of him to confirm that he was dead. A blend of horror and relief attended

the realization that Nikki’s uncertainty was over. More days would

pass before the obvious was confirmed, that his back-seater was gone,

too. A perfect missing-man formation zoomed overhead at the sunset memorial

service. We gathered to honor, remember, and grieve the loss of our friends

around those flags, lowered to half-mast since Boot’s discovery.

I understood at last. ![]()

In

need of normalcy

In

need of normalcy

By Kevin Henry *81

PHOTO: Kevin Henry *81, pictured here in Afghanistan, reviewed CARE’s relief initiatives in Iraq.

Kevin Henry *81 is advocacy director of CARE U.S.A.

Last August 19, I arrived in Baghdad on a United Nations flight from Amman. My first stop was the U.N. headquarters at the Canal Hotel. An Australian colleague from the CARE International office in Iraq met me, and we had a quick lunch at the U.N. cafeteria before leaving the compound at 3 p.m. Our Iraqi drivers then took us to our office across town in one of CARE’s fluorescent green vehicles, the latest in antitheft devices.

An hour and a half later, news of a massive explosion at the Canal Hotel reached us. Over the hours to follow, we learned the full extent of the tragedy. Most prominent among the victims was Sergio Vieira de Mello, the U.N. special representative for Iraq, whose contributions in Iraq, East Timor, and elsewhere had earned him widespread recognition. Less attention has been paid to the other 22 dead and dozens of injured, among whom were friends and colleagues of my CARE-Iraq hosts.

Despite the tragic start to my visit, I carried on. The purpose of my trip was to undertake a firsthand review of the key policy issues that CARE has been highlighting in its advocacy work on Iraq over the past year. I spent considerable time meeting with CARE’s Iraqi and international staff, counterparts in other international nongovernmental organizations (N.G.O.s), members of Iraq’s emerging civil society organizations, and representatives of the U.S. government and the office of the Coalition Provisional Authority (C.P.A.). I also visited several hospitals, primary health care centers, and water treatment plants rehabilitated by CARE since the war.

Not surprisingly, the issue foremost in everyone’s minds was security. The U.N. bombing was the latest and most dramatic in a series of attacks targeting humanitarian organizations. Apart from the risks facing aid workers, ordinary Iraqis continued to live in fear, uncertain as to whether it would be safe enough to send their children back to school when the summer holidays ended in late September.

Beyond security, unemployment was the most pressing problem. Since July, the C.P.A. had made progress in making regular salary payments to government employees, but the majority of the Iraqi population – and the overwhelming majority of young men – remained idle and without means to support their families. This was a recipe for disaster. Iraqis also anxiously awaited improvements in essential public services. With temperatures in excess of 120 degrees in Iraq in August, shortages of electricity and water added further fuel to an already volatile mix.

As I left Baghdad after my one-week visit, I reflected on the dilemma in which the Iraqi people and the U.S. occupation authorities find themselves. What Iraqis most urgently need are tangible signs of progress and the return of some sense of normalcy to their lives. They want jobs to support their families, and they want to safely send their children to school. Nearly four months after the end of the war, Iraqis had yet to see basic services return to even their dismal prewar levels.

Those who oppose a return to normalcy are doing their best to undermine

progress, sabotaging electrical transmission lines and attacking humanitarian

organizations. As a result of the August attack at the U.N., numerous

international organizations and N.G.O.s evacuated some or all of their

international personnel. If this trend continues, it could be the beginning

of a vicious downward spiral, with slowed reconstruction assistance feeding

a climate of Iraqi dissatisfaction. The international community must work

closely with the people of Iraq to ensure that does not happen. ![]()

Rebuilding

Iraq, pothole by pothole

Rebuilding

Iraq, pothole by pothole

By Michael Meese *00 and Richard Lacquement *00

PHOTO: Above, left, David Petraeus *87, commanding general of the 101st Airborne Division (left), with Mosul Mayor Ghanim Al-Basso (with tie). Above, right, Michael Meese *80 is flanked by Richard Lacquement *00 (right) and the mayor.

Col. Michael Meese *00 and Lt. Col. Richard Lacquement *00 were special assistants to Maj. Gen. David Petraeus *87, commander of the 101st Airborne Division, in Mosul last summer.

Summer 2003. It was uplifting to see the vigor of the Iraqis. During trips in and around the city of Mosul in northern Iraq, we witnessed the energy and vitality of Iraqi society: marketplaces crowded with people, neighborhoods being cleaned, satellite dishes popping up, construction crews filling potholes, street-side entrepreneurs selling an array of goods, traffic police reasserting authority over tangles of vehicles, and children playing in open lots and calling “Hello, Mister!” to passing troops.

Twice a week we attended the meetings of the governing council of Nineveh and the city of Mosul along with Maj. Gen. David Petraeus *87, commander of the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne Division. We were with the division to assist with local governance issues. The 25 members of the council – a diverse array of Arabs, Kurds, Christians, Muslims, Turkomen, and Yezidis – worked closely with the Coalition to press forward with rebuilding infrastructure, government, and civil society.

Working with the city council and other citizens of Iraq, we helped Iraqis struggle with the challenges of emerging from a corrupt, authoritarian central government

and economic system. These people worked hard to regain control of local government, begin the first steps towards democratic accountability, privatize economic enterprises, and establish communications among themselves and with the rest of

the world. They were eager to learn; each of us gave lectures on economics

and governance in Mosul University’s economics and political science

departments. Daunting as the tasks are, the Iraqis’ enthusiasm and

commitment are unmistakable and inspiring. ![]()

The

war not on TV

The

war not on TV

By Robert Dunham ’88

PHOTO: Air Force Reserve pilot Robert Dunham ’88 at the seat of his KC-10.

Rob Dunham ’88 is a major in the U.S. Air Force Reserve. His civilian job, as a pilot at United Airlines, was eliminated while he was stationed in Bulgaria to fly missions into Iraq.

The war in Iraq was a cold, snowy affair. I’m sure that’s not what you saw on TV, but I was there – trust me, it was cold. I fought the war from an Eastern Orthodox country with Christian icons for sale on every other street corner. But even my small unit had embedded media tagging along, a pair of Associated Press reporters who lived, flew, and drank with us.

Wearing the uniform and defending the nation is not my full-time job. As a pilot for United Airlines, I normally spent March and April enduring the last of the winter weather headaches in the Northeast and worrying about spring thunderstorms across the Midwest. But in late February I was activated and left my home in New Jersey for Burgas, Bulgaria, a city on the coast of the Black Sea with a good-sized airport and not much else.

How does an airline pilot end up getting sent off to war? I am a “citizen soldier,” a member of the Air Force Reserve. It’s a major time commitment – at least four to five days a month for pilots – but it’s also a rewarding form of national service in the Princeton tradition.

On September 11, 2001, I knew that several of my United coworkers were among the casualties in the terrorist attacks. I knew all the flight attendants on UAL 93, the flight that crashed in Pennsylvania. So last year, when my unit needed volunteers to deploy to the United Arab Emirates for Operation Enduring Freedom, the war in Afghanistan, how could I not go? I proudly spent a month flying into combat over Afghanistan, continuing the fight my colleagues had begun months before.

I did not have such a personal tie driving me to volunteer to fight in Iraq. Tying Saddam Hussein to September 11 seemed far-fetched; despite the president’s assertions, I found it hard to believe that Iraq posed an imminent danger. I volunteered to go in part because I’m not about to let my unit fight a war without me. As a soldier I don’t get to pick which policies I agree with; my duty is to support the chain of command.

Our first hurdle in Bulgaria was transforming the airport and small Bulgarian army camp across the street into living quarters and working space for almost 400 people who would perform our mission, flying KC-10s into combat over Iraq. That number includes the aircrew, aircraft maintenance, intelligence, security forces, communications specialists, medical personnel, civil engineers, and others. It would take more than a week for the tent city to be completed, and more than two for the chow hall. But it was far better to go downtown for the local shopska salad.

I fly the KC-10, a military version of the civilian airliner DC-10. We use it as a tanker, an airborne gas station greatly extending the range and duration of Air Force and Navy fighters, bombers, and other airborne assets. Once the Turks opened their airspace, we had a straight shot across the Black Sea and Turkey, right into northern Iraq. The flying, for the most part, was spectacular. Most of our refueling tracks were over the rugged, snow-covered mountains along the Iraq-Turkey border. They were shooting at us in the track near Mosul, but other tracks were over “friendly” areas of Kurdish-controlled Iraq, or Turkey. We flew almost every day, at all hours of the day. The pace was exhausting, but once the 173rd Airborne jumped into northern Iraq, we knew there were Americans on the ground below who were getting less sleep and certainly were in far more danger.

Then it all ended. We found ourselves with lots of time and very little

flying to fill it; a few weeks before Princeton Reunions, we packed up

and left. Now I look forward to returning to the citizen half of “citizen

soldier.” ![]()

Despair

flowed from a river that once brought luck

Despair

flowed from a river that once brought luck

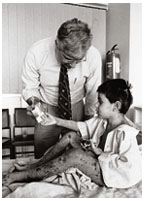

By Michael Viola ’59

PHOTO: Dr. Michael Viola ’59 examines a burn victim at a pediatric hospital in Baghdad.Michael Viola ’59 is founder and director of Medicine for Peace (www.medpeace.org), a medical relief and humanitarian organization dedicated to caring for children who are victims of war.

Iraqis have a pessimistic view of life. They were nurtured on the first recorded story of human mortality – the epic of Gilgamesh, the part-man, part-God, king of Uruk in Babylon. They endured Saddam Hussein and his thugs for more than 30 years, and came to believe that the economic sanctions, often referred to as “the strangulation” in Arabic, would never end. But even the stoic Iraqis have been horror-struck by the recent war and the occupation.

My colleagues and I at Medicine for Peace have been working in Iraq since 1991. Touring the hospitals today, we see the dire situation faced by ordinary Iraqis, particularly children. With the complete breakdown of law and order, and the continued uncontrolled violence, hospitals cannot provide even minimal services. Basic medications looted from hospitals have not been replaced, and hospital staff, especially nurses, face the risk of being mugged, abducted, and raped.

Children are seen in hospital emergency rooms with traumatic injuries, either from bullet wounds or bomb blasts; the children often are caught in the crossfire between vigilantes and looters, or are shot by nervous soldiers of the Coalition Provisional Authority. Unexploded munitions, particularly American cluster bombs and munitions abandoned by the Iraqi army, are a major hazard; unsuspecting youngsters think they are toys. Power outages make it impossible to purify water, leading to a surge in childhood dysentery. Thirteen years of sanctions have left a quarter of Iraqi children under five chronically malnourished. They are easy prey for infectious organisms.

These are not new problems, but they are growing worse. For centuries, the Euphrates River had brought prosperity to the people in Diwaniyah, in central Iraq. During the Gulf War, the coalition forces bombed electrical power plants, water, and sanitation facilities along the northern course of the Tigris and Euphrates, resulting in the discharge of thousands of tons of untreated sewage into the rivers. By the time the polluted water reached Diwaniyah, it was brimming with organisms that cause human disease. The river was the only source of water for cooking, bathing, and relief from the insufferable summer heat.

I recall going on rounds of the pediatric wards at the local hospital with Dr. Samaya Salah, the director; though that was in 1995, I see the same things today. The fans and ventilation system were at a standstill, and hot, smothering air hung in the corridors. Metal cribs with sick children lined the hallways and patient rooms. We entered a large ward and examined the child in the nearest bed. She was an infant, with a colorless fluid dripping from an intravenous bottle down plastic tubing and through a needle in the crevice of her arm. Her tiny body had no muscle, just transparent skin draped over skeleton. Dark, staring eyes were sunk in a skull that appeared too large for the rest of her body. A belly swollen with fluid accentuated her bony, pencil-thin legs. She had deep sores at the cracks of her lips. Clumps of her reddish-brown hair fell on the white bed sheet.

The child labored to move air in and out of her chest, and took long pauses between breaths. I tried to listen to her chest with my stethoscope, but when I touched her or gently moved her onto her side, she screamed. It was a high-pitched screech that came from the back of her throat. Only children suffering from malignant malnutrition cried like that. I scanned the room; a chorus of other children was squawking in the same way. The child’s mother, a young woman draped from head to toe in a black abaya and veil, sat at the edge of her crib. She had a thin, weather-beaten face marked with traditional Bedouin tattoos. She patiently fanned her daughter with a piece of used X-ray film, attempting to cool the child’s body and to keep the flies off her eyes.

Dr. Samaya read the patient’s history: Donya was a five-month-old girl who weighed 3.8 kilograms, hardly more than when she was born. She came from a poor tribal family. Food was scarce, so her mother had difficulty producing sufficient breast milk. Then the child developed constant, watery diarrhea from the bad water. She had a high fever for five days, and went in and out of coma. I told Dr. Samaya that I was concerned that this child would not live much longer.

Each bed held a child with uncontrollable watery diarrhea, bloody diarrhea,

or typhoid fever; I suspected one case of cholera. All the children were

malnourished. It did not matter if they were Shia, Sunni, Kurd, Turkoman,

Chaldean, Assyrian, or Yezidi. War had reduced them to an indistinguishable,

pathetic collection of bones. ![]()

When war comes home

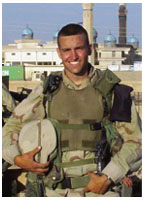

By Bethany Witmer Gasperini ’01 and Geoffrey Gasperini ’01

Geoff Gasperini ’01 with the Third Amored Cavalry Regiment in Fallujah.

Geoff Gasperini ’01 is serving in the Army with the Third Armored Cavalry Regiment, based in Fort Carson, Colorado, and now in Fallujah, Iraq. His unit is expected to remain in Iraq through next spring. Bethany Gasperini ’01 teaches high school biology and oceanography. The couple spent their first wedding anniversary, in May, apart.

Bethany Gasperini writes:

As a coleader of the family-support group for Geoff’s troop, I have had the opportunity to see the war through the eyes of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. Offering their husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons (our unit is all-male), these brave family members have endured months of uncertainty in order to serve the United States. Often handling needs that run well beyond their means, the women give of themselves constantly – working, mothering, fathering, providing, loving, and caring – to ensure that their husbands return to stable homes. (At times, though, war takes its toll in unexpected ways, and we have seen wives send separation papers to be signed by their husbands overseas. Such times are truly devastating.)

Overall, we support one another, offering comfort when none of us has received a letter in weeks. We are excited by news of fellow wives receiving phone calls from husbands, though they can speak only for a few minutes.

We also have endured months of frustration at the seemingly antiquated system put in place to offer our loved ones essential supplies and mail. At one point we heard that the mail system was worse than in World War II. Thankfully, it recently improved, to the delight of many families here at Fort Carson, Colorado.

Geoff Gasperini writes in a summer letter to Bethany:

We’ve settled into a routine of one day conducting checkpoints, the next day base security, back to checkpoints, then again to security, and so on. We’ve had some interesting moments at the checkpoints. Some are serious – busting vehicles with multiple illegal weapons like AK-47s, MP-5s, and even hand grenades, or confiscating huge sums of cash and gold bars from a stolen car.

Other moments are more humorous – cars full of drunk Iraqis interested in dancing around us and offering us their whiskey and beer, or the time when we had a shepherd drive though our checkpoint. He had three sheep in the back seat. When we opened the trunk, there were three more sheep back there!

Bethany continues:

The above description was written right before a catastrophe befell Geoff’s squadron, while soldiers were manning a similar checkpoint in Fallujah. Two men were killed and nine wounded when occupants in two vehicles opened fire on the Americans. The tragedy was most sobering for families here at Fort Carson, even though it went unmentioned in the letters from the soldiers. The wives continue to provide meals for the widows and their families.

Today I delivered a meal to a woman who recently lost her husband, and we had a chance to visit. He had endured a shrapnel injury to the head, and suffered brain damage. He died a week ago from a brain aneurysm. Amazingly, the wife talked about how fortunate she had been to see her husband before he passed. She said that he had been able to mouth words to her, and to gesture, which also showed his spirit.

In surviving such a loss, she and her three children are keeping to

routines and are talking a lot about her husband. She said her strength

lies in how proud she is of him for giving his utmost throughout his entire

life. What an amazing woman! ![]()

A

different mission

A

different mission

By John A. Basso *00

John Basso *00 stands in front of an abandoned Iraqi tank that was painted by local children.

John A. Basso, who received a master’s degree in public affairs, is a major in the U.S. Army.

I arrived in Iraq in late May. Twelve years earlier I had been in Kuwait as a scout platoon leader in an armored cavalry regiment. Then as now, it was hot, and oil fires lined the horizon. (Fortunately in Iraq, these fires were natural gas burnoff.) But Kuwait was a nearly featureless desert, whereas Kirkuk, Iraq, has rolling fields of wheat, and trees dot the landscape. The improvement in physical environment matched my outlook.

In Kirkuk and Tikrit, I worked as the economic development officer for the Fourth Infantry Division and the 173rd Airborne Brigade. Every day, my fellow soldiers and I worked hand-in-hand with Iraqis – Kurds, Arabs, Turkomen, and Assyrians – to rebuild their country. We worked to fix sewage systems, restart cement factories, open banks, improve hospitals, and to secure peace. We worked to pay the same Iraqi soldiers we recently had fought.

It was immensely satisfying work. And several Woodrow Wilson School classmates were doing it along with

me. My guess is that just as I did, they daily used the skills that

Princeton taught them. ![]()

How to win the peace

By Rick Barton

Rick Barton, a lecturer at the Woodrow Wilson School, is codirector of the Post-Conflict Reconstruction Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, D.C., and former deputy high commissioner for refugees at the United Nations. He was a member of a five-person team invited by the Pentagon to provide an independent review of postconflict progress in Iraq. The report and other studies are available at www.csis.org.

Our only welcome was a pack of four mangy stray dogs guarding the domed planetarium. It was early July, 110 degrees in the late afternoon’s dry, desert heat, down from 130 degrees earlier in the day. The dogs got agitated at the sight of us, and their barking echoed through the empty remains of Basra University. There was no other life on this campus, until three young British commandos appeared from behind one of the dozen concrete shells. Neither dogs nor soldiers had protected the place when it mattered.

There had been some intense fighting in Basra, though the hollowed-out buildings finally had been gutted not by war, but by industrial-strength looting that swept the university after the British soldiers had passed through. Seats and writing surfaces were gone, along with light fixtures, doors, windows, books, wiring, and almost everything else. Fires had been set. Occasionally, we would see a charred transcript or test.

We stopped in a lecture hall, wondering why Iraqis would allow such destruction. Two locals joined us and answered our questions with one of their own: How did the Coalition let this happen? Our British escort, now responsible for rebuilding the campus, pressed the argument, and it became heated.

How could we find ourselves in a disagreement between Iraqis who despised Saddam Hussein and the Coalition that had ended his three decades of tyranny? This was not a question of culpability, but of the frustration that comes from awful events, a precarious time, and an enormous reconstruction with slight preparation. Intimidation continues, stymieing fresh opportunities.

Peace must be won. Achieving public safety, self-governance, justice and reconciliation, and economic and social well-being will require an even greater commitment than the wizardry of war. An expanded international coalition and Iraq’s people will have to develop a mutual trust and a shared vision of basic freedoms and open, local ownership.

In order to succeed, Iraq’s renewal must take root in places like

Basra University, without dogs or soldiers, where a secular mix of young

men and women can develop into a new generation of democratic leaders.

![]()

Reporting

from Karbala

Reporting

from Karbala

By Theola Labbé ’96

Theola Labbe ’96, second from right, interviews women at Karbala jail.

Theola Labbé is a reporter for the Washington Post.

My first instinct when I arrived in Iraq last summer was to take everything in. Men strolled around in the searing temperatures wearing dishdashas, traditional long robes. Lines at the gas station ran for miles. Merchants at tiny straw huts sold tepid soda in cans from nearly every Baghdad street corner

One day I went to Karbala, a holy Shiite city south of Baghdad. I wore a full-length abaya and a hijab head covering, appropriate dress for a woman in a religious Muslim city. I met with the Karbala police chief and toured the police station, ending at the women’s cell.

Many Iraqi women, especially those in rural communities, stay at home with their children, so I had had few opportunities to interview women. I wondered about their lives. With a few steps into a cramped cell, I had my first chance to hear and tell some of their stories.

The prisoners rushed toward me, their arms outstretched as they gushed Arabic phrases and planted kisses on both sides of my face. Kulfa Abdali Musa, 44, and her two daughters, Suad, 22, and Miad, 19, were being held on murder charges. “Please,” the mother said, “I want to get out but I have no money for a lawyer.”

Another woman stood out to me because she was older, about the age of a grandmother, and didn’t offer up her story. She stood off by herself and started to cry. Later, the U.S. soldiers in charge of the jail told me about assaults on female prisoners, and other poor conditions. The woman crying in the cell, the soldiers said, was serving time in place of her daughter, who had an infant; a single mother could not serve time with her child.

The daughter was accused by her brother-in-law of murder, but witnesses

said she could not have done it. An Iraqi judge would hear her case the

next day. My pen and notepad would be there. ![]()