January 28, 2004: Features

|

Brian Earl ’99, Fifth-leading scorer in Princeton history with 1,428 points (Al Bellow/Getty images)

Palestra: March 3, 1998 Princeton 78, Penn 72 (O.T.) (william thomas cain/Getty images)

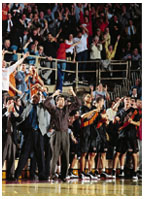

Palestra: February 9, 1999 Assistant coach John Thompson ’88, left, and coach Bill Carmody cheer a 50–49 win. (Beverly Schaefer)

Pete Carril arrived in 1967, and the Penn rivalry started to buzz. (Jamie Squire/getty images) |

Of

Tigers and Quakers

Despite

changes on the court, there are few sports rivalries more intense than

Princeton—Penn basketball

By Kathy Orton

Every good rivalry needs an antagonist. The rivalry between Princeton and Penn in men’s basketball is no exception. For years, Princeton Coach Pete Carril served as the foil for Penn fans. When Carril retired in 1996, the Quakers’ faithful turned their attention to Brian Earl ’99.

Oh, how they hated Earl, a Philly-area high-school star who spurned the local Ivy League school for Princeton. His stoic demeanor irritated them. His ability to make clutch shots drove them to distraction. They wanted nothing more than to see him fail.

But Earl was no failure, he was a winner. In his first three seasons at Princeton the Tigers won three Ivy League titles. His junior year, Princeton ranked No. 8 in the Associated Press poll, the highest since 1967, when the Tigers were ranked fifth. By the first Princeton-Penn game his senior year, the Tigers had won 35 straight Ivy League games.

That kind of success breeds confidence – or, some might say, arrogance. Whatever it was, Earl had plenty of it when he took the court to warm up before what most regard as the preeminent game between Princeton and Penn, February 9, 1999.

Earl could have picked any spot on the court to warm up, but he chose the one closest to the Penn student section. He started shooting jump shots. Swish. Swish. Each time he made a basket, Earl took a step back. Swish. Swish. Pretty soon, he was standing only inches away from the red-and-blue-clad fans. He could feel their breath on the back of his neck.

“I remember backing up behind the sidelines,” Earl recalls. “They had security guards standing right behind me. I just kept backing up. I knew I was getting to them. I really enjoyed it.”

“You can just see 50 kids standing this close behind him, just screaming in his ear,” says Princeton Coach John Thompson ’88, then an assistant to Coach Bill Carmody. “He just keeps banging away, doesn’t move. It wasn’t like, ‘Let me go to the other side of the court to get away from these guys.’ He just stood there.”

Earl’s pregame braggadocio seemed misguided after Princeton fell behind 29—3 late in the first half, 33—9 at halftime. But the Tigers rallied from a 40—13 second-half deficit and staged the fourth-biggest comeback in N.C.A.A. Division I history, defeating Penn, 50—49.

| Princeton–Penn

by the numbers: Number of times Princeton and Penn have met: 208; Penn leads series, 113–95 Ivy League

Championships: N.C.A.A. appearances:

Overtime games: 14 Games decided

by three points or less: Princeton’s

largest margin of victory: Penn’s

largest margin of victory: Longest winning

streak: At Penn: At Princeton:

Neutral sites:

Last 10 meetings:

|

Of all the games played between the schools, none symbolizes the rivalry better than that one. It had everything – wild swings, magnificent shots, heartbreaking misses, moments of unrestrained elation, and periods of profound despair. Anyone who was at the Palestra that night can attest it was the most incredible game they ever witnessed. It remains the most vibrant thread in the tapestry of games that, woven together, form one of the greatest rivalries in college sports. Like its better-known counterparts, Duke vs. North Carolina in basketball and Army vs. Navy in football, Princeton vs. Penn has all the components of a good sports rivalry – passion, respect for the opponent, distinct styles of play, and two schools with very different identities. What distinguishes this rivalry from the others, however, is its winner-take-all element.

“In simple terms what it meant [to beat Penn] was that you had a good shot at winning the [Ivy League] title,” says Carril, now with the Sacramento Kings. “They were always in your way and Princeton was always in their way.”

North Carolina can lose to Duke twice, beat everyone else on its schedule, and still go to the N.C.A.A. tournament. It stings the Tar Heels to listen to the Blue Devils brag about their superiority. But other than that, losing to Duke has very little impact on their season.

On the other hand, if Princeton beats every other team on its schedule, but loses twice to Penn, the Tigers not only have to listen to the Quakers gloat but they also miss the N.C.A.A. tournament. Because the Ivy League is the only Division I conference not to have a postseason tournament, the regular-season winner earns the league’s automatic bid to the nationals. Only on rare occasions does the name of the winner not begin with the letter “P.”

No other league has seen two teams dominate the way Princeton and Penn have, although recent years have seen other teams close some of the gap. (Last year, Penn won the Ivy championship, followed by Brown and Princeton.) In 33 of the last 35 seasons, one or the other, or both, have won the regular-season title. Only six times since the Ivy League’s inception in 1956 has the conference champion been a team other than the Tigers or the Quakers, which means that nearly every time these teams meet it is for the chance to play in the N.C.A.A. tournament. “For all intents and purposes, both games are championship games,” Thompson says. Say what you will about urban versus suburban, one school’s academic reputation versus the other’s, team versus individual, when it comes down to it, the fuel that makes this rivalry burn is who goes to the N.C.A.A. tournament — and who doesn’t.

The rivalry wasn’t always as intense as it is today. During the Ivy League’s formative years, Princeton worried more about Columbia and Cornell than Penn. “My sophomore and senior years, the best team in the league – other than Princeton – was really Cornell,” says Gary Walters ’67, Princeton’s director of athletics. In March 1965, Princeton and Cornell played a game to decide the Ivy League title. The game was watched by more people than any other at that point in Princeton basketball history – 3,000 saw it live; 1,700 watched it on closed-circuit television. The Tigers, who had lost at Cornell earlier in the season, 70—69, left no room for doubt in this game. Princeton set the school’s single-game scoring record, routing Cornell, 107—84 – a record broken later that month when Princeton defeated Wichita State, 118—82, in the N.C.A.A. tournament. Walters’s teammate Bill Bradley ’65 had some of his best nights playing Cornell. Twice, Bradley scored 40 or more points against that school.

Geoff Petrie ’70, Princeton’s seventh-leading all-time scorer, recalls the rivalry with Columbia. In his sophomore year, Columbia won the Ivy League title, defeating Princeton in a playoff, 92—74, at St. John’s. Princeton went 14—0 to win the league title in 1969, with Columbia finishing second. When Petrie was a senior, Columbia finished second to Penn, the Ivy League winner; Princeton was third.

Still, the Princeton-Penn rivalry began to take hold during the Ivy League’s first decade. Princeton dominated its series with Penn then, winning 15 of 20 games. The Tigers also won five league titles during that span while the Quakers never finished better than second in the standings. Despite the lopsided matchup, the passion already was growing. Former Princeton Coach Willem “Butch” van Breda Kolff ’45, who guided the Tigers from 1962 to 1967, was quoted on a plaque in the Palestra as saying, “I just never liked Penn – don’t know why, just never did. And I don’t think they ever liked us much either.”

Art Hyland, Princeton’s captain in 1963, shared his coach’s feelings toward Penn. He especially didn’t care for Quakers captain John Wideman, later to become known as the novelist John Edgar Wideman. Although the two are cordial now, there was no love lost between them after four years of playing against each other. It was at the training table before the final Princeton-Penn game in 1963 that Hyland’s teammates, along with van Breda Kolff, goaded Hyland into playing a trick on Wideman. “This is the kind of stuff that makes you say to yourself, ‘Why did you do those things when you were young and how are people finding them out now?’” Hyland says. His teammates wanted him to wear a hand buzzer and buzz Wideman when the two shook hands after the pregame meeting between the captains at center court. Hyland agreed, but nearly backed out at the last minute.

“Everyone is saying, ‘You’ve got to do it. You’ve got to do it,’” Hyland recalls. “As I was slipping it on behind my back, I felt like I could hear everybody in the stands saying, ‘He’s going to do it.’ We shook hands, and I buzzed the guy and he kind of looked at me like I was from outer space. As the night went on, we were fortunate to win so it became a fond memory that we all laugh about when we get together.”

Hyland’s handshake incident aside, it wasn’t until Carril arrived at Princeton in 1967 that the rivalry really began to buzz. If Princeton-Penn could be boiled down to its basic elements, what would remain at the bottom of the pot would be one inanimate object and one very animate being. On the Penn side would be the Palestra, one of the most glorious and historic venues in which to watch a basketball game. On the Princeton side would be Pete Carril.

The rivalry “was probably most intense when Pete Carril was at Princeton because he made it intense,” says Alexander Wolff ’79, a senior writer for Sports Illustrated. “He didn’t have much use for Penn and made it clear he didn’t.” More than anything, Carril wanted to win. He especially wanted to win Ivy League titles. And because Penn usually was the team preventing that, Carril grew to dislike the Quakers.

In Carril’s 29 seasons coaching the Tigers, Penn went through six coaches. The Quakers coach who stayed the longest is current coach Fran Dunphy, who faced Carril for seven of his 14 seasons at the school. The first Penn coach to tangle with Carril was Dick Harter.

“Dick Harter was a very organized, Marine-type coach, who didn’t show a lot of emotion,” says Penn Director of Intercollegiate Athletics Steve Bilsky, who played for Harter. “Pete Carril was just the opposite.” When things looked good, Bilsky recalls, Carril would gesture animatedly. When they looked bad, he would slump on the bench. “So he became a character,” Bilsky says. “From the standpoint of how our fans reacted to that, you couldn’t have asked for somebody to be a better target. The ‘Sit down, Pete’ [chant] started here.”

Hyland was Carril’s assistant coach when Harter was at Penn. It was during this time Penn began to emerge as an Ivy League contender. According to Hyland, Carril was particularly frustrated when Penn brought in players who didn’t qualify academically at Princeton.

“He had some real issues at the time [with Penn’s recruiting],” Hyland says. “They could recruit some players that we couldn’t. There was a guy who went there from New York that we really wanted to come to Princeton. We couldn’t get him [into school].” Wolff says it was about that time Carril started calling Princeton’s admission office “heartbreak hotel.” “Penn was a burr under Carril’s saddle in part because of Princeton’s [academic] circumstances and the admission office,” Wolff says. “I think that made it a little bit tougher those years that he did lose to Penn.”

In his book, The Smart Take From the Strong (1997), Carril had this to say: “There have been accusations down through the years about recruiting and admission practices at Penn, questions about Penn’s standards for athletes, whether they were lower than those for the rest of the league. My comment on that is that each school has its own way of doing what it needs to do, its own mission, its own sense of economy. Whatever Penn does is its own business and only should be noticed and mentioned when there’s a violation of the rules. The rest of it is just crap.”

Carril, who was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1998, won 514 games at Princeton, made 11 N.C.A.A. tournament appearances, and won 13 Ivy League titles. He also ended his Princeton career in 1996 with a losing record against Penn, finishing 27—34 overall against the Quakers.

Although the 50—49 game in 1999 stands out the most, there were two other games in this rivalry that ended 50—49. (Princeton fans recall that was also the score of the Tigers’ emotional loss to Georgetown in the first round of the 1989 N.C.A.A. tournament.) The first occurred January 4, 1975. Going in, Princeton wasn’t given much of a chance. The Tigers had lost eight of their last 10 games against Penn. The Quakers had won five consecutive Ivy League titles.

On this night, however, the Quakers couldn’t make a basket. They missed shot after shot, which allowed Princeton to take a 30—22 halftime lead. After Princeton led by 16 with 16 minutes to play, Penn closed to within one with a minute remaining. John Engles had a shot to win the game for the Quakers, but the ball caromed off the rim.

Later in the season, the Tigers went on to lose to the Quakers, 75—57, which enabled Penn to win its sixth straight Ivy League title. All was not lost for Princeton, though. The Tigers closed the regular season by winning 13 straight games and knocked off Holy Cross, South Carolina, Oregon, and Providence to win the N.I.T. championship in New York.

The other 50—49 game did not end in Princeton’s favor. On March 4, 1980, Princeton and Penn met in a playoff game at Lafayette College to determine which team would represent the Ivy League in the N.C.A.A. tournament. The Tigers looked very un-Princetonlike that season. They opened up losing 11 of their first 13 games, including an eight-point loss to Oral Roberts and a 10-point loss to Nevada—Reno. But Princeton finally hit its stride going into the Ivy League season. After losing to Penn, 58—42, the Tigers won their next six league games. They pulled to a tie in the standings with the Quakers with a 79—68 victory over Penn at Jadwin Gym. Princeton could have taken the lead the following weekend, but on the same night that Penn lost at Columbia, 55—51, the Tigers lost to Cornell, 67—47. The teams ended the regular season tied at 11—3, forcing a playoff.

In the playoff, flustered by Princeton’s zone defense, Penn needed more than five minutes to make its first field goal. The Quakers, who later went through a six-minute stretch without a basket in the first half, managed to go up 27—25 at halftime. Gary Knapp ’83, a freshman who led the Tigers with 14 points, scored on an eight-foot jump shot with 39 seconds remaining to put Princeton ahead, 49—48. Penn’s James Salters answered with an 18-foot jump shot on the other end. With one last chance to win it, Knapp took a shot from nearly the same spot he made his last basket. The ball bounced off the back of the rim as time expired.

Freshman Tiger Craig Robinson ’83, who finished with 11 points that night, recalls that he didn’t remember feeling nervous going into the game. “I don’t think I knew enough [about the rivalry] to be nervous my freshman year,” he says. Like many players when they first come to Princeton, Robinson didn’t appreciate the magnitude of the Princeton-Penn game. But by the time he was a senior, Robinson understood the implications of losing to the Quakers: no Ivy title, and no trip to the N.C.A.A. tournament. “I remember thinking about how I didn’t want to lose a game to Penn my senior year,” Robinson says. “I wanted to beat them. I wanted to win the league. I didn’t want it to be a playoff. . . . It really kicked in for me in that playoff game against Penn. After that, I wanted to win every game I played in.”

More than 15 years later, Earl and his teammates learned the same lesson. As a freshman in 1996, Earl played in what is widely considered Princeton’s most improbable N.C.A.A. tournament win. The No. 13-seeded Tigers shocked defending national champion U.C.L.A., 43—41.

“The U.C.L.A. game meant more to Princeton University, the alumni, Coach Carril, and the nation in some respect than it did to the players,” Sydney Johnson ’97 was quoted in Princeton’s media guide last season. “If you ask the guys on the team, I think they’d say the playoff game against Penn to get to the tournament meant much more to us.”

Earl, as usual, was restrained after the U.C.L.A. win. Matt Langel, Earl’s best friend from eighth grade and a guard on the Penn team in 1999, remembers the contrast between the emotion Earl showed after that game and his demeanor following Princeton’s 50—49 win against Penn in 1999. “If you go back and look at the film when they beat U.C.L.A., [the rest of the team is] going crazy and he’s just barely pumping his fist,” Langel says. “To see the picture of him running up and down the sidelines [after Princeton beat Penn in 1999], that was one of the best Penn-Princeton games ever.”

Games like the one in 1999 make one wonder why this rivalry remains so far beneath the radar outside the Ivy League. ESPN.com failed to mention Princeton vs. Penn in its February 2003 article on the best rivalries in college basketball. Writer Andy Katz’s top five were Duke vs. North Carolina, Oklahoma vs. Oklahoma State, Xavier vs. Cincinnati, Missouri vs. Kansas, and B.Y.U. vs. Utah. “Princeton-Penn clearly is one of the best rivalries in college basketball because they’ve both dominated the Ivy League for decades,” Katz acknowledges. “At some point we probably should [broadcast the game]. It probably doesn’t get the recognition it deserves in part because it is not on national television.”

Within the last couple of seasons, the Ivy League has become increasingly competitive. In 2002, Yale forced the league’s first-ever three-way playoff. This past season, Brown came within a total of 11 points of knocking off league champion Penn. Parity, however, doesn’t seem to diminish the rivalry between Princeton and Penn. “I think it even adds to it,” Walters says. “Basically it means you can stumble even less.

“Every game has an added significance.” ![]()

Kathy Orton covers basketball for the Washington Post.

Jadwin: March 6, 2001 Princeton 68, Penn 52 (Frank Wojciechowski)

Jadwin: March 6, 2001 Princeton 68, Penn 52 (Frank Wojciechowski)