March 10, 2004: Features

|

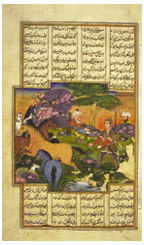

Many Shahnama illustrations contain verdigris pigment, which is corrosive to paper. The lower right corner of the illustration shows significant loss of paper which, long ago, had been repaired using uncolored acidic paper.

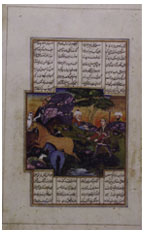

After conservation, the old repairs, backings, and glue have been removed. Losses were filled in with toned Japanese paper, and a sheer Japanese paper with special adhesives was applied.

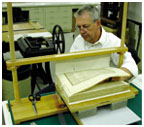

The condition of the Shahnama manuscript prior to treatment in 1997: The binding, above, had become fragile and damaged, and the leather of the spine deteriorated. (Photo: scott husby) Sewing on the binding was also broken, allowing the leaves to loosen and detach. also above, an example of how the verdigris, the green pigment used in the paintings, had eaten through the paper, causing the center panel of this page to detach from the surrounding border.

After the preservation work was finished, Scott Husby resewed the manuscript using a traditional bookbinder’s sewing frame, attaching one gathering of the manuscript textblock at a time to a slotted support made of laminated linen and paper. (Photo: Robert Milevski) |

New

life for an old treasure

Library curators

complete seven-year preservation project

By Mark F. Bernstein ’83

ABOVE: Left, Isfandiyar

battles dragon in page from

newly preserved Shahnama. (Department of Rare

Books and Special Collections, Princeton University

Library/photograph by John Blazejewski)

Researchers at Firestone Library have new access to an old treasure, as curators recently completed a seven-year project to preserve a 17th-century copy of the Shahnama, an illustrated version of the Persian epic legend. The Shahnama, which means “Book of Kings,” would have been a proud ornament in any prosperous Middle Eastern home of the time, the equivalent of a modern coffee-table book.

This particular Shahnama, which runs some 1,040 pages, was purchased by Robert Garrett 1897 and donated to Princeton in 1942. It is believed to have been written and illustrated in Persia in about 1654; Garrett purchased it from a dealer, Kalebdjian Frères, in 1924.

Until now, intense study of the manuscript had been impossible because of its poor condition. Persian manuscripts tend to deteriorate, in part because of the hot and often humid climate in that region, but largely because of the nature of illustration. Illustrators of the period liked to use a green ink made of oxidized copper, known as verdigris. Though it produces a lovely, subtle shade of green, verdigris is extremely corrosive and over the years had eaten through the paper on which Garrett’s Shahnama was painted. The problem had become so serious, says Don Skemer, Princeton’s curator of manuscripts, that anyone trying to turn a page in the book would lift out the unpainted border, and the large square illustration in the middle, as well as verdigris-painted pieces inside it, would fall out.

The curators worked to conserve the manuscript but not, Skemer notes, to restore it. Restoration, he explains, connotes fooling the observer by making something look new again. Conservation or preservation, on the other hand, seeks to stabilize the work so that it can continue to be used. Flaws are fixed as best they can be to preserve the work’s appearance, but researchers should be able to distinguish, upon close inspection, what is original and what is not. Furthermore, all techniques to conserve a document should be reversible by future curators, so the work can be done better if techniques improve.

That is important because much of the work in conserving this particular Shahnama involved undoing preservation work done more than a century ago. To protect the verdigris drawings, glassine sheets, similar to wax paper, had been attached around them using animal glue. Ted Stanley, the chief conservator on this project, spent months painstakingly removing that glue with cotton swabs, a labor that was made even more difficult because the solvent he used tended to make the underlying ink run. Working with a microscope, Stanley then tried to fit the remaining pieces of verdigris back into place, like a huge jigsaw puzzle, treating them with magnesium salts to stop the paper from corroding any further.

Once the pages were restored, another curator, Scott Husby, stitched the whole thing back together. Unlike European binding, in which leaves of a book are sewn to reinforcing ribs, Islamic binding used a chain-stitch technique in which all the pages were sewn to each other with a delicate silk thread. If the thread broke, the whole manuscript would unravel. Husby compromised, using a stronger, more European binding technique while still enabling the book to lie flat when opened, in the Islamic style. He then reattached pieces of the original goatskin cover over a new core, thus preserving this 350-year-old manuscript for future scholars to appreciate.

The manuscript is one of more than 10,000 Middle and Near Eastern manuscripts – including four Shahnamas – collected by Garrett, a college track star who won two gold and two silver medals at the first modern Olympic games, in Athens in 1896. Following graduation, Garrett organized an archaeological expedition to Syria, a trip which spurred his lifelong interest in the history of writing in all cultures.

The library works on a handful of major preservations each year, and

there is always a backlog. Such projects are done only when curators can

squeeze an hour here and there from their more routine repairs –

usually, 12,000—15,000 each year. ![]()

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is a senior writer at PAW.