April 21, 2004: Notebook

Number of international applications falls

Four sciences integrated to form new course

Number of international applications falls

International |

2001—02 | 2002—03 | 2003—04 | 2004—05 |

Undergraduate |

2383 | 2109 | 2430 | 1934 |

| Graduate | 4065 | 4908 | 4441 | 3370 |

International applications to Princeton for the 2004—05 academic year dropped 20 percent among undergraduates and 24 percent among graduate students; the decline included disproportionate application decreases from Chinese students and students from secondary schools outside the United States. Reports by the Council of Graduate Schools and the Chronicle of Higher Education suggested that several factors contributed to the decline, most notably a cumbersome U.S. student visa process.

The problem could affect international researchers and faculty as well, ac-cording to David Redman, associate dean for academic affairs at the Graduate School. “There is a growing concern that this country’s relatively easy access to the world’s brainpower may be restricted,” Redman says, “and there may be some long-term implications.”

Departments have not complained about a lack of quality among this year’s graduate applicants, but they do have plans to improve graduate recruiting, to compete with more aggressive efforts from colleges in Western Europe, Asia, Canada, and Australia. Dean of Admission Janet Rapelye says her office will reexamine undergraduate recruiting for international students.

Though very few visa requests from Princeton students are denied, visa delays concern students, according to Mary Idzior, the University’s director of visa services. The most common problem is establishing a student’s intent to return home, which requires specific documentation. Last year, two students — one graduate student and one undergraduate — chose not to enroll because of visa issues.

A February report from the General Accounting Office estimated that processing for the Visas Mantis system, which clears postgraduates and scholars in fields designated as security or technology-transfer risks, takes an average of 67 days. The process generally does not affect undergraduates because the State Department’s technology-alert list applies only to advanced study.

The technology-alert list has existed in various forms since the early part of the Cold War, but its role has changed since September 11. Instead of focusing only on specific countries, security officials now pay attention to a student’s field of study, regardless of nationality. The latest version of the list, released in 2002, includes nuclear energy and weapons-related fields, as well as urban planning, architecture, and several natural science disciplines, in the belief that chemistry and biology can be used in weapons technology.

The other major post-9/11 addition to the visa process is the Student and Exchange Visitor Information System (SEVIS), a Homeland Security Department database. The information collected in SEVIS is similar to that on pre-9/11 forms, with the addition of a student’s local and home addresses, but it is stored electronically. Visas also require a photograph of the student and a hologram for authentication. With the additional steps in the process come additional delays. “Although the technology has helped a lot – it has increased security, it has made things more efficient – it takes a while,” Idzior says.

The University provides guidance on visa procedures from the moment students are admitted, but Hilary Herbold, an associate dean of undergraduate students, believes the process is a source of anxiety. “International students approach the process with a lot of trepidation because there are so many unknowns,” she says.

To counterbalance that anxiety, the dean of undergraduate students’ office does its best to give international students a warm welcome when they arrive on campus. About two-thirds of freshmen from abroad participate in a voluntary preorientation, where they meet the deans, interact with upperclassmen from the International Students Association at Princeton (I.S.A.P.), and take care of practical needs, such as shopping.

I.S.A.P. president Malvina Goldfeld ’06 says that international

students form an important part of the Princeton community. But to compete

with peer institutions, she adds, the University needs earlier, more aggressive

international recruiting. Since applying to college is “more of

a personal initiative” for international students, a little recruiting

she says, can have a significant impact. ![]()

By B.T.

PAUM |

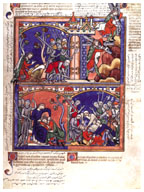

On view at the Art Museum through June 6 is one of the greatest illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Ages. The exhibit, The Book of Kings, features 26 pages from the 13th-century Picture Bible, on loan from the Morgan Library in New York. At right is a page depicting the story of Samson; in the top panel Samson has removed the posts from Gaza’s gate and is taking them to Hebron. The bottom left shows Samson being shorn of his protective locks, and on the right his captors blind and bind him.

“This manuscript is full of blood and guts and all kinds of excitement,”

says Assistant Professor of Art and Archaeology Anne Marie Bouché,

who is using the exhibit in her course, Medieval Art in Europe. “One

of the problems I have is getting people to engage in manuscripts. They’re

in Latin, the pictures are little, and they’re all religious subjects.

This manuscript is so rich in detail.” Bouché’s students

will each pick a motif from the Picture Bible (Samson’s haircut,

for example) and draw it for themselves; then, using library resources,

such as the Index for Christian Art, research their motifs.![]()

David Botstein, director of the genomics institute, will teach portions of a new cross-disciplinary science curriculum. (Photo by Frank Wojciechowski) |

Modern scientific research, says David Botstein, does not obey boundaries. Chemists incorporate physics, physicists delve into biology, and biologists use computer science to analyze massive data sets. The world has become multidisciplinary and increasingly quantitative, and the standard college curriculum is not keeping pace.

Botstein is not alone in his diagnosis – professional groups such as the National Academy of Sciences have recommended more integration in science education – and the chance to explore alternatives was one of the things that brought Botstein to Princeton, where he serves as director of the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics. Most of Princeton’s peer institutions have interdisciplinary science centers, but they generally focus on integrating research at the graduate or professional levels. Botstein has assembled a team of eight professors who will take a new approach to undergraduate science this fall in CHM/COS/MOL/PHY 231—234: an integrated, quantitative introduction to the natural sciences.

Traditionally, science majors learn the basics of each discipline (chemistry, molecular biology, and physics) in separate courses. But introductory material for majors and nonmajors is separated, and the different levels of sophistication create language barriers. “It’s very clear that the communication problems are there,” Botstein he says. “It’s very clear that they set in quite early in our current education, that the silos of the different specialties have walls that are very high.”

The new introductory course of study aims to keep the walls from forming by teaching the same material to majors and nonmajors, displaying the practical connections between fields, and incorporating the mathematical concepts scientists need. About 30 freshmen will have the opportunity to take the six-semester course, which begins with a double class in each semester of the freshman year, and continues with a single class in each semester of the sophomore year. The freshman classes will meet five days a week for lectures, once a week for precepts, once a week for labs, once a week for computer lab, and once a week to do problem sets.

Students will learn to program computers using Java in the first six weeks of the course, enabling them to solve problems that involve large amounts of data. “[The course] is going to be mercilessly quantitative, but it’s not going to require you to be a mathematician in the strict sense,” Botstein says. “It is going to require you to think quantitatively.” The scientific lab program, organized by Lewis-Sigler Fellows Maitreya Dunham and William Ryu, will incorporate modern equipment and address real-world questions.

Professor and Nobel laureate Eric Wieschaus will join Botstein in teaching the biology portions of the course; Professors Michael Hecht and John Groves will lecture on chemistry; Professors William Bialek and Daniel Marlow will teach physics; and Professors Olga Troyanskaya and Bernard Chazelle of the computer science department will teach advanced computation. The director of the University’s teaching center, Linda Hodges, a biochemist, will help to coordinate the faculty team.

Bialek, whose work involves both physics and biology, says that Botstein’s approach is unique because it builds from the ground up, not with incremental changes to an existing program. The challenge is to add breadth to introductory science without sacrificing depth, which requires critical viewpoints from each field represented. “It’s a genuine collaboration among all departments,” Bialek says.

Another distinctive element is the course’s “just-in-time” approach. Instead of teaching prerequisite material in advance and then reviewing it later when it comes up, the instructors will now teach the material at the moment it is needed. “What we won’t do is have some kind of axiomatic presentation of [for example] conditional probability and say ‘this is really useful, you’ll see later,’” Botstein says.

Hecht, who previously taught introductory chemistry, says the new course

takes advantage of two elements that make Princeton an extraordinary place

to study science: the laboratories of a major research institution and

the classrooms of a small undergraduate college. “The course merges

them together,” he says. “It teaches science from the perspective

of how it’s done in the real world.” ![]()

By B.T.

Joann Mitchell, Princeton’s vice provost for administration, will join the administration of the University of Pennsylvania as vice president and chief of staff July 1. She will report to Amy Gutmann, Penn’s president-elect, who is currently Princeton’s provost. Mitchell came to Princeton in 1993 from Penn, where she was director of affirmative action. At Princeton, she was associate provost and affirmative-action officer from 1993 until 2001, when she was named vice provost for administration.

Lynn Russell, a former Princeton assistant professor of chemical engineering who was denied tenure in 2002, filed a lawsuit against the University in March, seeking compensatory damages of more than $1 million. Russell alleges that gender discrimination and retaliation by her department chairman prevented a fair and unbiased tenure review. Russell, who currently teaches at the University of California—San Diego, appealed the tenure decision at Princeton, but a separate committee upheld the previous vote.

Popular history professor Andrew Isenberg, who was denied tenure by the University last year, has accepted a tenured position at Temple University in Philadelphia. Isenberg, who received the President’s Award for Distinguished Teaching in 2001, appealed the University’s tenure decision, but the appeal was denied. At the time, more than 500 students signed a petition asking the University to reconsider its decision.

The Princeton Committee on Prejudice sponsored Black-Jewish Relations Week in March. Events included a forum with historians Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Murray Friedman, a screening of the 1999 documentary film From Swastika to Jim Crow, and a joint presentation by a Polish Holocaust survivor and a Rwandan genocide survivor.

Friedman, a professor at Temple University, said the 1950s and ’60s marked a golden age for black-Jewish relations, when groups like the Anti-Defamation League “thought of themselves less as Jewish agencies and more as civil rights groups,” helping Southern blacks to get fair-employment and fair-housing laws passed. The relationship deteriorated over time, and according to Gates, a Harvard professor and this year a visiting fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study, recent polls indicate that anti-Semitism is “a spreading canker within African Americans’ academic discourse.” He said African Americans owe it to themselves to condemn racism in all its forms.

Beginning this month the University has begun using 100-percent recycled

paper for general office needs. The new policy, formulated by the Princeton

Environmental Oversight Committee, will affect paper for copying machines,

printers, and fax machines. Official University stationery is not included

in the policy. The recycled paper will cost 40 cents more per case than

the paper formerly used. ![]()