Have an opinion about this issue of PAW? Please take a minute to click here and fill out our online questionnaire. It’s an easy way to let the editors know what you like and dislike, and how you think PAW might do better. (All responses will be kept anonymous.) |

April 6, 2005: Notebook

After a record, fund raising drops

Breaking ground – psychology

Probing how the brain sorts the people we meet

A tale of the young Fitzgerald, set to music

Examining the war on terrorism

(Illustration: Ron Barrett) |

A

spotlight on Einstein’s ‘miracle year’

Celebrating the influence, and the Princeton connections, of

the famed scientist

On the night of April 18, if all goes as planned, Princeton will be aglow, from the top of the Fine Hall tower to the grounds of the Graduate College. The University is slated to be the starting point for a relay of lights around the world to honor Albert Einstein on the 50th anniversary of the physicist’s death.

The project, titled “Physics Enlightens the World,” was conceived by Max Lippitsch and Sonja Draxler, professors at Karl-Franzens University in Graz, Austria, as a memorial for Einstein and a fund-raiser for physics education in developing countries. And since every chain reaction needs a successful start, Lippitsch and Draxler are hoping for a big, bright turnout in Princeton. “They’re definitely interested in how we are doing,” said local coordinator Claire Gmachl, an associate professor of electrical engineering who has recruited physics and engineering students to help spread the word.

The spotlight will shine on Einstein from many angles in 2005, the 100th anniversary of his annus mirabilis, or miracle year, when at the age of 26 he published four seminal papers that revolutionized the field of physics. The light relay is one of several events at the University and in the Princeton community that will celebrate Einstein’s work, which still plays a prominent role in physics, from quantum computing to cosmology. Said Paul Steinhardt, the Albert Einstein Professor in Science, “It’s hard to touch on an area of physics that doesn’t feel his influence.”

Princeton still feels Einstein’s influence as well, as a source of community pride, from a makeshift museum in the back of a Nassau Street clothing store to the borough hall plaza, where a sculpture of Einstein, donated by artist Robert Berks, will be unveiled in April. While he never held an appointment at the University, Einstein lived near campus for more than two decades. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from Princeton when he first lectured at McCosh Hall in 1921, months before he received the Nobel Prize. As PAW reported at the time, he was already “the most conspicuous figure in the modern scientific world.” Twelve years later, Einstein fled Nazi Germany and came to the Institute for Advanced Study, then housed in the original Fine Hall (now Jones Hall).

Steinhardt is coordinating the physics department’s festivities honoring Einstein and the World Year of Physics, including a series of lectures devoted to Einstein’s life and work. On May 27, at the start of Reunions weekend, the department will host a program for alumni and the campus community. Princeton professors Edward Witten *76 and J. Richard Gott *73 and Hideo Mabuchi ’92 of Caltech will talk about applications related to Einstein’s research.

Beyond the physics department, the Princeton U-Store has brought authors to campus to talk about Einstein’s legacy, including John S. Rigden, who wrote about the miracle year in Einstein 1905: The Standard of Greatness (Harvard, 2005). The Institute for Advanced Study, which is celebrating its 75th anniversary this year, will devote portions of its Founders Day program on May 20 to lectures about Einstein’s work. The University is working with Palmer Square Management Corp. and a nonprofit group called Princeton Occasions to convert a vacant lot behind Palmer Square into “Quark Park,” a summer showcase of science and art similar to the Writers Block constructed on the same site last year.

Photographs often show Einstein in a rumpled gray sweatshirt with hopelessly disheveled white hair, but Caltech historian Diana Kormos-Buchwald, director of the Einstein Papers Project, said this year’s celebrations should go beyond that image of the “wise old icon” of science. “Very few people show us the young Einstein,” said Buchwald, who spoke on campus in February, “and it’s the young Einstein who we’re celebrating this year.”

For Gmachl, whose interest in Einstein goes beyond the light relay,

there is some value in seeing both the person and the scientist. “I

wouldn’t necessarily insist on separating it,” she said. “One

of the things Einstein does is he makes it clear that science is made

by people, and that’s still true.” ![]()

By B.T.

|

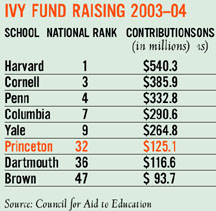

After a record, fund raising drops

Contributions to Princeton fell by more than $100 million in 2003—04 to $125.1 million, according to an annual report from the Council for Aid to Education. Annual Giving collected $36.5 million in 2003—04, its second-highest total in history. But overall donations — including funds from foundations, nonalumni individuals and corporations — declined to their lowest level since 1995—96.

After ranking 17th in contributions among all U.S. academic institutions in 2002—03, the University dropped to 32nd for the year ending last June 30, and to sixth among Ivy League schools. Harvard, Cornell, Pennsylvania, Columbia, and Yale each ranked in the top 10 nationally.

Brian McDonald ’83, the University’s vice president for development, said the Council for Aid to Education survey measures cash flow in a given year, not total pledges, and a drop was not surprising after the record-setting receipts of $227.5 million in 2003. “Considering that we are not in a major, comprehensive fund-raising campaign, and considering our size, I would characterize our performance last year as very solid,” McDonald said. At a faculty meeting March 7, President Tilghman echoed McDonald’s sentiments about the University’s performance relative to its size. She said that Princeton’s participation percentage for alumni contributors outpaces all peer institutions: 61 percent of alumni donated to the University in 2003—04.

Contributions to American colleges and universities totaled $24.4 billion

in 2003—04, up 3.4 percent, according to the Council for Aid to

Education. Alumni donations are still the most significant source of voluntary

support for higher education, comprising 27.5 percent of all gifts. Foundations

are close behind (25.4 percent), followed by nonalumni individuals (21.3

percent), and corporations (18.0 percent). McDonald said that schools

with graduate programs in medicine, business, or law have an edge in attracting

corporate and foundation donations. ![]()

By B.T.

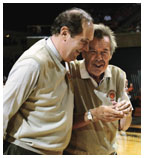

Bill Bradley ’65, left, listens to his former coach, Willem “Butch”

van Breda Kolff ’45, during a March 5 ceremony commemorating the

1964—65 men’s basketball team’s trip to the NCAA Final

Four. The Tigers finished 23—6 that year, and Bradley scored a Final

Four-record 58 points in the national consolation game against Wichita

State. ![]()

Breaking

ground – psychology

Probing

how the brain sorts the people we meet

Our brains categorize the people we meet in a matter of milliseconds, says Professor Susan Fiske, but thinking of people as individuals can combat stereotypes. (Ricardo Barros) |

When psychology Professor Susan Fiske was growing up in Hyde Park on Chicago’s South Side, racial integration helped define the neighborhood. In a high school production of Jean Anouilh’s Antigone, a black student played King Creon; a white student played his wife, Eurydice; another black student played the title character; and Fiske played Antigone’s sister, Ismene. “Here we were, this little multi-racial family on stage,” she recalls, “and it just seemed right.”

Does that mean Fiske and her classmates were unaware of racial distinctions? No, she says — no one is “color-blind” when it comes to matters of race or ethnicity. Inside the brain, we constantly are categorizing the people we encounter, sometimes in a matter of milliseconds, and the natural process can have negative consequences, such as stereotyping or biases. “The people who are motivated overcome it,” Fiske says. “They may have that initial millisecond reaction, but they don’t stop at their superficial first reaction.”

In her research, Fiske uses a combination of psychology and neuroscience to examine stereotyping and prejudice, including the different ways that the brain handles category-based and individual-based reasoning. The work is part of the emerging field of social neuroscience, an area that Fiske says generates a “palpable excitement” from those involved. This spring, Princeton will host a meeting of experts in the field — a relatively small group. “You can put them all in one room right now,” she says. “But that won’t be true in 10 years.”

Princeton’s involvement in social neuroscience is made possible by a combination of interdisciplinary cooperation and cutting-edge technology, including a functional magnetic resonance imaging machine (fMRI) that tracks the blood flow to show which parts of the brain are operating at a given time. Brain activity provides a window through which researchers can view human responses to specific situations. For example, in a study published by Fiske and lead author Mary Wheeler *01 in the January 2005 issue of Psychological Science, white participants who were asked to put photographs of black people in one of two age categories (over-21 or under-21) showed activity in the amygdala, the part of the brain that alerts a person to emotionally significant events. Responding to questions about the photographed person as an individual, such as whether he would like a certain vegetable, the same participants had no amygdala activation. The research suggests that how we think about people — individually or categorically — affects how we respond to them.

Fiske’s ongoing work with graduate students Amy Cuddy and Lasana Harris explores the categories into which we separate people and the emotions associated with those categories. Based on previous research, the emotions can be defined by two indicators — degrees of warmth and of perceived competence. Elderly or handicapped people, for example, elicit pity, an emotion with a high degree of warmth and a nominal feeling of competence; wealthy people tend to evoke envy, generating less warmth but an acknowledged level of competence. By separating the different kinds of categorical responses and seeing how the brain reacts, Fiske hopes to find specific “emotional signatures” in brain activity.

The information that the brain provides does not show that we are hard-wired

for hatred or fear, Fiske says. Rather, it gives us a better understanding

of how people interact. “It helps to know what kinds of fundamental

systems are implicated when people are making sense of other people,”

she says. “That doesn’t mean they’re unchangeable, but

it does mean that they probably are operating largely outside of awareness.”

![]()

By B.T.

“Despite finding no smoking gun, the United States and the United Kingdom prefer to believe in faith-based intelligence. … National intelligence is indispensable, but it must apply critical thinking.”

Hans Blix, former chief U.N. weapons inspector, during a March 8 lecture

in Dodds Auditorium on “Weapons of Mass Destruction, Terrorism and

Security.” Blix is the author of Disarming Iraq: the Search

for Weapons of Mass Destruction.

![]()

A tale of the young Fitzgerald, set to music

Cara Reichel ’96 and Peter Mills ’95, creators of The Pursuit of Persephone, met as members of the Princeton Triangle Club.

Above, a publicity photo of F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17 in costume for the Triangle Club’s 1915—16 production, “The Evil Eye.” He was described as the musical’s “most beautiful show girl.” (F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers, Manuscripts Division, Princeton University Library. By permission of Harold Ober Associates Incorporated.) |

Comeuppance is sweet: F. Scott Fitzgerald ’17 is returning to the New York stage, more than eight decades after his play closed before reaching Broadway. The husband-wife duo of Cara Reichel ’96 and Peter Mills ’95 has created a musical, The Pursuit of Persephone, that memorializes Fitzgerald’s early years. Inspired by the literary icon’s Princeton-themed novel, This Side of Paradise, the show will debut this month.

Set circa 1915, The Pursuit of Persephone follows Fitzgerald’s life both at Princeton, where he hobnobs with buddies (and fellow future literati) Edmund Wilson ’16 and John Peale Bishop ’17, and along the railroad tour route of the Princeton Triangle Club show, where successions of debutante balls and cross-dressing antics become the norm. Running through it all is a thread of doomed romance, an account of Fitzgerald’s bittersweet infatuation with elusive Chicago heiress Ginevra King.

According to its creators, the musical’s historical perspective — Fitzgerald’s naïve and frivolous youth, before he meets would-be wife Zelda — offers insight on the writer’s stylistic development.

“The story of Ginevra King, where he gets dumped, is really what allowed him to write The Great Gatsby,” said Reichel. “[Persephone] is a nostalgic story about the things that happen in our youth that shape the rest of our lives.”

Reichel and Mills, who met and began dating as undergraduate members of the Triangle Club, have collaborated on five other musicals through the Prospect Theater Company, an off-off-Broadway group they helped found with other University alumni. Finding inspiration for this particular show, they say, was easy.

“At Princeton, F. Scott Fitzgerald is one of the great mythologies you’re indoctrinated with, so we’ve always been haunted by this past, this feeling of oneness with Fitzgerald’s ghost,” said Reichel.

Hard-nosed scholars of Princetoniana may be pleasantly surprised. The title is a takeoff of the 1913—14 Triangle show, In Pursuit of Priscilla; Fitzgerald would write for the following three Triangle shows. Composed by Mills, Persephone’s score is faithful to the authentic style of pre-Jazz Age Triangle Club tunes. He and Reichel conducted research in the University archives, studying primary sources of Triangle Club history and the recently unveiled collection of King-Fitzgerald letters.

“In the letters, I looked for the way King expressed herself,” said Mills. “A lot of it has become fodder for dialogue and for her character — what words, what expressions she uses.”

The Pursuit of Persephone is scheduled to run at New York’s

Connelly Theatre, 220 East 4th Street, from April 30 to May 22. ![]()

By Jordan Paul Amadio ’05

Illustration by STEVEN VEACH |

Birds of a feather

When animals migrate in flocks or forage in packs, their movements seem

to require complex coordination. But a model from two Princeton researchers

published in the Feb. 3 issue of Nature suggests that the mechanism behind

these movements may be relatively simple. Researcher Iain Couzin and Professor

Simon Levin of the ecology and evolutionary biology department joined

with colleagues from two British universities to create a computer simulation

that took into account the instinctive desire of animals to stay in a

group, and the influence of certain informed members pointing the group

in a preferred direction. The model revealed that groups could reach their

objective (a food source, for example) with great accuracy, even when

relatively few members had information about the destination. The larger

the group, the smaller the proportion of guides that was required. In

addition to providing insight into biological topics such as social learning,

the findings could be useful in the design of robots that work together

in coordinated groups. ![]()

Laurie Simmons, Walking John Hancock (Chicago), 1992, Princeton Art Museum Purchase, anonymous gift“ |

FOR PRESENTATION AND DISPLAY: SOME ART OF THE 1980s” is the subject of a new exhibition at the University Art Museum that runs through June 12. Focusing on art and commercial culture, the exhibition includes 18 of the period’s most influential artists, including Laurie Simmons, Richard Prince, and Cindy Sherman. Artists Dara Birnbaum, Sarah Charlesworth, James Casebere, and others will take part in a symposium, “Working Through the ’80s,” on Saturday, April 14, at 4:30 p.m. in McCormick 101. The museum is open to the public without charge Tuesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and on Sunday from 1 to 5 p.m. It is closed Mondays.

“THE FABRIC OF THE COSMOS” will be discussed Wednesday, April 6, by Columbia University Professor Brian Greene, a theoretical physicist and author of The Elegant Universe. He will describe how the understanding of space and time has been transformed over the last 300 years, from Newton to Einstein to contemporary string theory that suggests more dimensions of space than those we can see. No expertise in physics will be presumed. The lecture will begin at 8 p.m. in McCosh 50; it is free and open to the public.

New York Times senior writer Jason DeParle will discuss his 2004 book, “AMERICAN DREAM,” on Monday, April 11, at 4:30 p.m. in Bowl 016 of Robertson Hall. The book follows three women who are part of one extended family before and after national welfare laws changed under the Clinton administration. The free lecture is the first in a series on children and families sponsored by the Woodrow Wilson School and the Center for Research on Child Wellbeing.

“A DEBATE ON EMBRYONIC STEM CELL

RESEARCH,” moderated by former University President

Harold Shapiro *64, will be held Monday, April 18, at 4:30 p.m. in Dodds

Auditorium, Robertson Hall. Participating will be Lee Silver, professor

of molecular biology and public affairs, and Dr. William B. Hurlbut, consulting

professor in human biology at Stanford and a member of the President's

Council on Bioethics. Shapiro is former chairman of the National Bioethics

Advisory Commission. The free program is open to the public. ![]()

Examining the war on terrorism

How to fight a war against terrorism will be the focus of a Woodrow Wilson School colloquium April 8—9. Keynote speakers include retired Gen. Anthony Zinni, former commander of the U.S. Central Command and an outspoken critic of the Bush administration’s military policy in Iraq; Hanan Ashrawi, secretary-general of the Palestinian Initiative for the Promotion of Global Dialogue and Democracy; and retired Maj. Gen. Giora Eiland, Israeli national security adviser.

Steven Barnes, assistant dean for external affairs, said the conference will examine issues such as who the terrorists are and what are they targeting, what kind of institutional structures are best suited to fight global terrorist networks, to what extent should U.S. policy target the roots of terrorism, how to assess the ethics of torture and detention, and what is the appropriate balance of civil liberties and security. The context of the conference, Barnes said, is “rethinking the war on terror within the Bush administration’s stated goal to expand democracy around the world.”

Taking part in the conference will be University faculty, other academic and think-tank researchers, journalists, and government officials. Anne-Marie Slaughter ’80, dean of the Woodrow Wilson School, will moderate a session on educating a new generation of government leaders to address terrorism.

All sessions are free and open to the public. Most of the sessions are

expected to be webcast live; go to www.wws.princeton.edu/coverstory.html

and click on the webcasts link on the top of the page. The conference

will coincide with the Wilson School’s graduate alumni weekend.

![]()

Three junior faculty members are among 116 U.S. researchers to receive Sloan Research Fellowships, awarded to stimulate fundamental research by early-career scientists and scholars of outstanding promise. The three are assistant professors MARKUS BRUNNERMEIER, economics; HELENE REY, economics and international affairs; and OLGA TROYANSKAYA, computer science. Each receives a grant of $45,000 over two years.

IVY CLUB has received approval from the Princeton Regional Planning Board for a 21/2-story addition that will include a two-story “great hall” and a basement “crypt” to be used for study space.

James Q. Griffin ’55, graduate president of the board of governors, said the club hopes to begin construction in spring 2006. Griffin said the club has been overcrowded since admitting women in the early 1990s, but said no expansion is planned beyond the current level of about 130 members. The addition was designed by Porphyrios Associates, the firm led by Demetri Porphyrios *80, which also designed Whitman College.

ROBERT HUTCHINGS, diplomat-in-residence at the Woodrow Wilson School and chairman of the National Intelligence Council from February 2003 to February 2005, has received the National Intelli-gence Medal of Achievement for his “effective leadership, broad strategic vision and commitment to analytic excellence.” Hutchings came to the University in 1997 as assistant dean of the Wilson School; he was on public service leave while chairing the National Intelligence Council.

SEAN WILENTZ, the

Dayton-Stockton Professor of History, came up short in his bid for the

Grammy award for best album notes. Wilentz was nominated for an essay

on Bob Dylan’s 1964 concert at Philharmonic Hall in New York City,

a show the professor had attended as a 13-year-old. Jazz historian Loren

Schoenberg won the Grammy. ![]()