|

|

January 25, 2006: Features

Photographer

Fazal Sheikh ’87

Portraits of people, not

just of their pain

By Katharine Greider ’88

Fazal Sheikh ’87 (Macarthur Foundation)

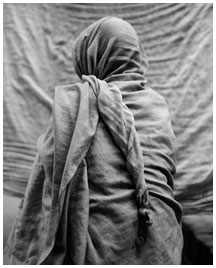

Sarla Goraye

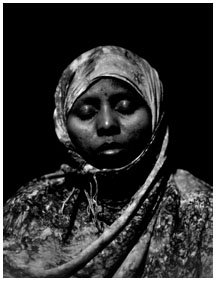

From A Camel for the Son, Anep Ibrahim Addan with her son Abdullai and daughter Ayen, feeding center, Somali refugee camp, Mandera, Kenya, 1992.

Above: From Ramadan Moon, Seynab Azir Wardeere, Asylum Seeker’s Center, Osdorp, The Netherlands, 2000. (Photographs © Fazal Sheikh) |

My husband died of a fever six months after we were married. He was 12 years old. I was only 5. His family said I was an unlucky person and I was to blame for his death. I was never taken into their household because they did not want me to bring them the same fate. So even though the marriage had never been consummated there was no chance I could ever be married again and I have carried this stigma for the rest of my life.

After my parents died I lived with my brothers for many years, but eventually they, too, died and 30 years ago, at the age of 50, I moved to Vrindavan, where I have lived in this home with the other widows ever since.

From Moksha (2005),

Vrindavan, northern India

Sheikh’s portrait of Sarla Goraye is at right.

Fazal Sheikh ’87 had every reason to be confident when, in 1992, he headed to a refugee camp in Kenya to make photographs of the scene. The well-traveled son

of an American mother and Kenyan-born father, Sheikh’s Manhattan upbringing had been privileged, his undergraduate years at Princeton distinguished, his career auspiciously launched with the Fulbright fellowship that brought him to Kenya. But when the plane landed and Sheikh’s photojournalist colleagues set to work forthwith, the young man’s self-assurance drained away. The scene was overwhelming. How could he render it?

Rather than tamp down this uncertainty and get cracking, Sheikh allowed himself to “fumble around” — a fumbling that yielded the very signature of his art: a respectful, patient, collaborative technique for portraying human beings in extreme circumstances. He got to know these Somali people shoved from their homes by violent conflict, who had lost dear ones and in exile continued to endure privation and threat; he asked for their “complicity,” as he puts it, in the work he was doing.

The newness of Sheikh’s approach was borne out in the arresting pictures he brought home, first from refugee camps in Africa and later from among Afghans displaced by Soviet occupation and the rise of the Taliban, impoverished Mexicans struggling to enter the United States, and, most recently, shunned widows living out their days in the ashrams of Vrindavan, India.

Many of these works are formal, yet intimate, portraits that bring the subject front and center while surroundings fall away in the near-abstraction of a spare tree in dappled light or the white-white of tent fabric. In portraits of Afghan children and elderly mujahedeen, one sees faces, close up; the intensity of attention to these faces — to the vein that delicately traces the temple of the elder, to the child’s hank of dark hair and ample, down-turned mouth — seems to say that there is no other person like this one anywhere. In their particularity the subjects become almost universal. In an image from the Somali work (opposite page), Anep Ibrahim Addan nurses her son Abdullai. She looks unsmiling into the camera, the tilt of her head complex, maybe a little playful; the nursing child has the far-off gaze of contentment, his hand curled around his ear. A daughter, Ayen, perhaps 7, looks down at the boy, her small hand resting in the maternal lap. We may not recognize the names Sheikh is careful to attach to these portraits, or the patterned drapery his subjects wear. But we know these gestures; when the photographer tells us son, daughter, sister, we know what he means.

These are not lurid dispatches from the disaster zone, but neither are they typical family portraits. They are too frank — that reflexive happy-face the camera elicits from Westerners nowhere to be found — and too accomplished, each “a very highly sensed aesthetic piece,” according to Peter Bunnell, recently retired as curator of photography at the Princeton University Art Museum. Nor does Sheikh neglect the political and cultural turmoil that drove these families into exile, or pretty up their suffering. On the contrary, text that accompanies images in exhibitions and in Sheikh’s five published monographs often unspools a tale of unspeakable cruelty and loss.

His book Ramadan Moon (2001) begins with images of leaves, sky, and moon that have a trembling, ecstatic quality, accompanied by quotations from the Koran and other Muslim texts. Then comes a series of facial portraits of Seynab Azir Wardeere (page 55) and, in her own voice, sweet memories of Ramadan in Mogadishu with her family. When finally we arrive at this subject’s time of woe, we nearly choke on its bitterness: father murdered before her eyes, raped and beaten in front of her children, separated from husband and daughter, betrayed by Dutch authorities who might have offered safe haven. Sheikh’s great insight about human nature is that you first have to see the person before you can fathom her suffering. Azir Wardeere’s victimization, he says, “changes the way you see her, but she’s not reduced to that one moment of trauma in her life.”

Sheikh’s audaciously humanitarian goal is to allow the viewer to see himself as “on an equal footing” with Azir Wardeere and other displaced people in poor, war-ravaged countries. His humanizing photographs surprise partly because they call to mind certain familiar images, but contradict their implications: for example, the “candid” journalistic renderings of famine-stricken refugees that fill the newspapers today — images meant to document events as much as people, and that too often provoke our pity, but not our identification, Sheikh says.

The recipient of numerous grants, most recently a 2005 unrestricted, $500,000 MacArthur “genius” award, Sheikh steers wide of the media as a means of disseminating his work. His pieces are owned by prestigious museums and well-to-do collectors, but he also has distributed thousands of books for free and published them on the Internet (www. fazalsheikh.org). Sheikh lives in Zurich. He feels increasingly alienated from an America he sees as intolerant of dissent in the aftermath of 9/11 and disappointingly resistant to placing that awful day in the context of a world convulsing with similar agonies.

How Sheikh came to his own empathy for the people he photographs is a complex affair. As a boy, he spent summers in his father’s native Kenya, and it was partly a fascination with paternal roots — his grandfather was born in what is now northern Pakistan — that motivated his first photographic explorations. Sheikh’s mother, a New Jersey native, took her own life when he was a young man; here is a measure of the “extreme heartache” that, Sheikh says, might permit any of us to empathize with others’ suffering. Asked about artistic influences, Sheikh names Lewis Hine, the documentarian of early-20th century New York, for his influence on such social issues as child labor and his aesthetic “knockouts.” But he dwells on Princeton photography professor Emmet Gowin, “basically like my family now,” because of the way he lives and works, and the way each is a lucid reflection of the other. “Emmet, day and night, handles his life in the same way that he handles his images,” says Sheikh. “You can’t erase yourself when you’re making the image.”

As he prepares for a new project exploring infanticide and the lives

of girls left at orphanages because their parents didn’t want to

raise daughters, Sheikh’s own life and collaborative work seem to

argue for a different metaphor of photography, perhaps one that de-emphasizes

the clicking shutter — the “taking” and “shooting”

and “getting” of images — in favor of the aperture,

an eye, that opens, exposing not only the subject, but the film, and the

photographer. ![]()

Katharine Greider ’88 is a freelance writer in New York City, and the author of The Big Fix: How the Pharmaceutical Industry Rips off Americans.